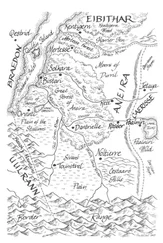

GREENRILL, NEAR TURTLELAKE

D'Abjan had been working this same piece of wood for the better part of the day, and still it wasn't right. It never would be. Every time he managed to plane it to the right shape, he'd leave too many rough edges. And by the time he smoothed them away, using the chisels, rasps, and smaller planes scattered over his father's workbench, the lines were wrong again. He was covered with wood-curled shavings, small chips, finer dust. So was the workbench, and the floor, and just about everything else in the shop. Yet he was no closer to finishing it than he had been hours ago. It just looked… wrong, and if he worked it any more, he'd leave this piece smaller than the matching one his father had already made for the other side of the chair.

He heard the door open and close, but he didn't turn. His father had been in and out all day long, delivering pieces, doing repairs, checking in with D'Abjan's mother and sisters, who were at their table in the marketplace, selling the last of the herbs and dye flowers to have come from their garden this year. Perhaps he'd forgotten something, or had returned for whatever tools he needed for his next repairs. Maybe D'Abjan would have a few moments more of peace before his father saw how poorly he had done. He should have known better.

"Let me see how it's coming along," his father said, trying to sound jovial, or encouraging, or anything other than what he was: resigned to yet another of D'Abjan's failures.

He crossed to where D'Abjan stood and hovered at the boy's shoulder. After a moment, he sighed. D'Abjan didn't need to look at his face to know that he was frowning, calculating the cost of the wasted wood, the delay in hours or days that D'Abjan's poor workmanship would cost him.

"You've tapered it too much," he said at last.

D'Abjan kept his eyes fixed on the workbench. "I know."

"You need to keep the plane level as you work a piece like this. You can't allow it to bite so deeply. A woodworker can always carve away more, but he can never replace what's already been taken out."

"Yes," D'Abjan said as evenly as he could. "You've told me before." "And yet still you don't heed what I tell you."

"I tried," he said, glaring at his father. "I told you I wasn't ready to do this."

"This is the third year of your four as an apprentice. By my third year, I was making entire pieces. Chairs, tables, benches. I made a wardrobe during my fourth year: top to bottom, all on my own. At this rate you'll still be doing piecework a year from now."

"Well, I guess I'll never be the woodworker you are, will I?" "That isn't what I meant."

"Isn't it?"

His father looked at him sadly. "Isn't it just as likely that my father was simply a better teacher than yours is?"

D'Abjan dropped his gaze, his cheeks burning. After a moment he shrugged.

His father stepped into the storage room and emerged a moment later with a new piece of the same maple D'Abjan had been working.

"Start it again," his father said. "Try making the shape right first, even if it turns out too big for the chair. We can work on getting it to the right size later. Together. But concentrate on this first."

He nodded. "All right."

His father patted his shoulder and started toward the door again. "I have one more repair to do over at the smithy. I'll be back soon."

"Father."

His father turned.

"Can I take a walk first, get out of here for just a bit?"

"I suppose," his father said, frowning slightly. "Not too long though. Madli's been waiting for her chair long enough."

D'Abjan began to take off his work apron. "I won't take long. I promise."

"Very well."

His father left their house. Moments later D'Abjan was out the door as well, though he took care to go in the opposite direction, away from the marketplace. Away from anyone who might see him.

He remained on the path for just a short while, strolling past the last of the homes on this western edge of Greenrill. Once he couldn't see that last house anymore-and no one there could see him-D'Abjan turned off the lane and ducked into the wood, fighting his way through the brush and pushing past low cedar branches to a small clearing he'd visited before.

There he found a freshly fallen tree limb-cedar, of course; it grew in abundance in this part of the highlands. He took out his pocketknife and peeled away the bark in long, smooth strips. Then he sat in the middle of the clearing and he began to draw upon his magic, his V'Tol. His power. He'd discovered that he could do this only a few turns before. Other boys his age here in the village had been talking about being able to do things. Some could start fires, others could speak with birds and foxes, coaxing them to take food from their hands. D'Abjan could shape. That's what the Qirsi called it. The real Qirsi; the ones who used their powers every day. He'd heard peddlers talking about them, about their powers. Shaping. He was a shaper.

Except that he wasn't. He was Y'Qatt. By using his magic, even once, even for an instant, he was violating the most basic tenets of his faith, going against everything that his mother and father had taught him.

He placed his hands over the wood, as he had so many times before, and he began to shape it, smoothing the edges, narrowing it at one end, turning it into the same chair arm he'd spent the morning trying to create in his father's shop. It was so easy, as natural as breathing, as immediate as thought. Whatever his shortcomings as a woodworker, he had taught himself to be a fine shaper. Too bad his father could never see what he had learned to do.

He'd heard what the Y'Qatt clerics said about V'Tol. Who among the Y'Qatt had not? V'Tol was life, it was the essence of what they were. All Qirsi, not just the Y'Qatt. Those who chose to use their magic as a mere tool, or worse, as a weapon, were squandering the gift of life given to all of Qirsar's children, a gift from the god himself. That was why using their magic weakened a Qirsi. That was why those who spent their power the way men and women of both races spent their coin in a marketplace died at a younger age than did those who held tightly to the V'Tol. It made sense.

But if Qirsar hadn't intended for his children to wield this magic, why had he made it so easy to use, so powerful, so satisfying? Why had he given them different abilities-shaping and fire, language of beasts and mists and winds, gleaning and healing? Why had he made the V' of at all? He wanted to ask this of his father and mother, of Greenrill's prior, of anyone who might be willing to give him an answer. But he knew that the question itself would so appall whoever he asked that he was better off remaining silent.

As it was, if his parents ever learned what he did in this clearing, they would be ashamed. They might banish him from their home or even from the village itself. So, after gazing for a few moments at the wood he had shaped, he tossed it onto the ground a few spans from where he sat, and drawing on his magic once again, he shattered the limb into a thousand pieces. This felt satisfying, too, though in an entirely different way. For just an instant, he could imagine himself as a warrior in one of the Blood Wars, fighting against the Eandi sovereignties, wielding this power he possessed in a noble cause. Of course, his parents would have seen this as a betrayal as well, a worse one perhaps than the simple conjuring he had done just a short time before.

D'Abjan exhaled heavily, then climbed to his feet and started back toward the dirt road. His father would be back at their house before long, back in the workshop, and would wonder where he'd gone.

As he approached the road, he peered toward the village, making certain that no one was watching before setting foot on the path. He hadn't taken two steps, however, when he heard a low groan from behind him. He gasped and spun, his heart suddenly pounding in his chest.

Читать дальше