Briar shrugged. “Stories get stretched when they travel.”

“But you are that pahan , are you not?” Turaba pursued.

“Maybe,” Briar said with another shrug. “Me and the girls always get talked about.”

Turaba looked at her master and made a flickering signal with her hand. Tentatively she asked Briar, “Can we not reach an accommodation?”

“I don’t appreciate people using street kids as pawns,” Briar told them. “Evvy’s scraped to live in this wonderful city for years. You owe her better than sending her into that house, if there’s a chance she’ll be risking her life.”

The mutabir sighed. “There have been poor since the birth of humankind, young pahan. It speaks to the generosity of your heart that you have taken this girl in, but know this, for every girl lifted from poverty, there are twenty more to take her place. No one could save them all.”

Not that you ever bothered, Briar thought, but he kept it to himself. He’d already pushed this man as far as was safe.

The mage inspected the crystal globe she still held.

“Will you at least keep your ears open for more information? You have been seen with members of the gangs involved—you may hear something. You may be invited to the lady’s house again.”

“Why bother?” asked Briar. “Her kinfolk will hush it up, no matter what.”

“If she has committed truly serious crimes, her own kin will want an end to her activities,” the mutabir replied. “Even nobles answer to the law. She cannot murder without consequences.”

“I’ll think about it,” Briar said flatly. “Can I go now?”

The mutabir drummed his fingers on a tabletop, then nodded. Briar turned and walked out, the skin on the back of his neck prickling. He was surprised at their restraint. Most law officials he’d known would bruise people first for defying them, then apologize later. He knew that law-keepers tended to walk softly around mages—why risk creating problems they might not be able to fix? — but this was the first time he’d experienced it personally. Which stories about him and the girls had filtered to this far place?

* * *

The house on the Street of Hares was quiet when he arrived late that afternoon. A lone cat—Briar thought it was the brown tortoiseshell Asa—napped in the middle of the dining room table. Looking at her in decent light, Briar realized she was pregnant.

“Wonderful,” he muttered, dumping his packs and parcels on the table. “Rosethorn?” he called. Asa looked at him, meowed a complaint, then went back to sleep.

“Workroom,” shouted Rosethorn.

“Evvy?” He walked toward the kitchen.

“In my room,” Evvy called. She sounded cross.

Briar reversed course and went to the door of Evvy’s new room. An invisible force halted him at the threshold. He looked down. A thin line of green powder lay across the sill. Touching it with his magic, he found it was the Holdall mixture Rosethorn kept in her stores. There were also lines of it across the windowsills.

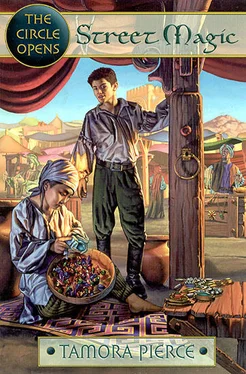

Evvy sat against the far wall in the middle of a nest of cats. She was toying with the stones she had brought from home and pouting.

“What did you do?” asked Briar. He fought to keep a grin off his face.

“I didn’t mean anything by it,” Evvy whined.

“She had her nose in the mouth of a jar of Must-Sleep powder and was about to inhale,” Rosethorn said tartly from the top of the stair. She stood with ajar braced on one hip. “I told her not to go poking in the workroom.”

“I wanted to know how it smelled,” grumbled Evvy.

Briar shook his head. “And if you’d taken a big whiff, you’d be asleep for months,” he informed her as sternly as he could. “You have to obey Rosethorn. She mostly doesn’t give orders without good reason.”

“Mostly?” Rosethorn murmured, coming down the stair. Briar stepped aside to let her pass. “Just mostly?”

“Sometimes you give orders to be crotchety,” Briar whispered as she went by. He watched as she put the jar by the front door. “What’s that?”

Rosethorn stretched, hands pressed against the small of her back. “I’m about set for those farmers,” she explained. “I’ve packed every last seed for the fields. You can help me bring it down here. Her, too.” Bending down, she dragged a finger through the line of powdered herbs across Evvy’s door. “Come make yourself useful,” she told the girl as the freed cats raced out. “And don’t get into anything.”

“I just wanted to see how it smelled,” Evvy grumbled as she followed Briar and Rosethorn upstairs.

The fruit of Rosethorn’s rooftop endeavors, the clover, bean, and corn seed harvested and mage-dried to keep them from rotting, had been packed into jars and sealed with wax. They had to be carried downstairs. So did a dozen sacks of grain. Rosethorn had poured her magic into them, giving them the strength to become a fast-growing winter crop, hardy enough to survive the rainy season. Last of all were small kegs of a growth potion, a small drop of which could fertilize an acre of land for years.

As soon as everything was clustered before the front door, they set about preparing supper. Briar had bought his cooked chicken on the way home; Rosethorn had made lentils and noodles during the day. Once the food was served, Rosethorn worked a protective circle to keep the mewing and yowling cats from climbing on the table.

“They’ll get fed,” she told Evvy, who seemed much chastened. “But we work hard for our food here, so we get to eat first.”

Once he’d devoured a bowl of noodles and lentils and a chicken leg, Briar asked, “Won’t you need me to help you in the fields?”

Rosethorn shook her head. “Most of the work’s done. I’ll be gone three or four days. You two will have to manage without me.” She glared at Evvy. “I’m putting wards on the workroom to keep you out. You don’t go in until you learn to read.”

Evvy nodded, eyes wide.

“Aww, you’re getting soft,” Briar teased Rosethorn. “Time was you’d have skinned anyone who fooled with your pots.”

“I may do that yet,” Rosethorn replied, with an extra glare for Evvy. “A mage’s workroom is not a spice merchant’s shop. Our brews can kill people, or worse. When do you start teaching her to read?” she asked Briar.

“Tonight,” he replied, carving more chicken. “I got her a surprise at the market.”

“Just make sure it isn’t a surprise for me, too,” Rosethorn said, wiping her lips. “Will you two be all right the time I’m gone? Earth temple would probably let you move into the guest house—”

Briar shook his head. “We’ll be fine.”

“Did the lady ask about me?” Evvy asked Briar. “What was her house like?”

Rosethorn propped her head on her hands. “Yes—what was it like?”

“The gardens are… very healthy,” answered Briar. “Especially the biggest one. And it’s fancy inside, all marble and stone inlays, expensive wood, silk, velvet, gilding. She asked about Evvy again, but I think she listened this time, when I told her no.” He added more details about the art he had glimpsed and what the lady wore, used to such descriptions after four years of living among females who wanted to know how others lived. He didn’t mention his conversation with the mutabir and his mage. The more he thought about it, the more it troubled him. Rosethorn would need a clear mind to do the work she intended to in Chammur’s fields. It could wait until she returned.

“I’ve been thinking,” Rosethorn drawled, when Briar finished. “It might be possible to reach Laenpa, across the border in Vauri, before the rains. An old friend of mine from Lightsbridge settled there—she’s written she has plenty of room for us, and that she’d like the company.”

Читать дальше