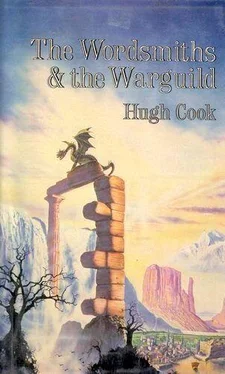

Hugh Cook - The Wordsmiths and the Warguild

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Hugh Cook - The Wordsmiths and the Warguild» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Wordsmiths and the Warguild

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Wordsmiths and the Warguild: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Wordsmiths and the Warguild»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Wordsmiths and the Warguild — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Wordsmiths and the Warguild», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Ondolakon'n-puru-sodarasonsee. Cha?"

"Cha," he said, experimentally.

She slapped his face.

"Why did you do that?" he said, sharp tears pricking his eyes.

She made no answer, but went into the females' building which was forbidden to him, returning shortly with a long stick which had a hook at one end. She spoke sharply, then set off. He followed, holding the claw-lined gourd, breathing in the heat which ascended from the coals.

Their clogs clicked down a broad, deserted street flanked by dull, squat pyramidal buildings. The street ended abruptly in swamp. They crossed a series of rickety bridges between swamp trees and swamp islands. Here and there, occasional bits of masonry obtruded from the chilly waters – a single column, or a bit of wall, or a stairway to nowhere. He blew on the coals to keep them alive. They glowed hot and red, relishing the life fed to them by his breath. He was glad that at least something in this cold, desolate universe appreciated his existence.

In the grey waters, he caught sight of their reflections. Dressed in their gross, bulking clothes of bark and moss and lichen, crowned with their swollen, shrouded headgear, they looked like strange, deformed insects.

The bridges ended. They had reached a place half swamp, half city. Huge, decayed buildings bulked up out of the grey waters. Paths and roads walked variously above and below water. The buildings were drenched in winter-withered vines; he saw that the dead vegetation was posion ivy.

"Lora-ko-lara-sss-daz'n'n'boro," she said, kicking together a few fragments of stick.

He guessed her purpose, and helped build a fire. They lit it with one of the hot coals from the gourd. Then, using the hooked stick, she raked down some dead poison ivy. When it was heaped on the ground, she set it alight. She passed him the stick. He did the same, keeping well clear of the ivy, for he knew better than to handle it, for all that it was dead.

"Shor-nash-n'esha-esha-ala'n-cha," she said.

Then clicked her tongue and walked away, heading back the way they had come. When he followed, she turned on him, screaming. She gave him a push. He retreated. She kicked the stick. He picked it up and began to pull down poison ivy. She clicked her tongue once more, slapped her elbow, then left him.

He worked all day. In the evening, another woman came and led him back to the settlement. There was a meal waiting, of sorts; it was prepared by women, it was served by women, and hhe ate amongst the women.

This, for a time, was the pattern of his days. He was woken at first light and served a solitary breakfast. Then he was led along the bridges to his place of work. He was never trusted to go alone. The person who took him would wait until he had a fire going and had started on the poison ivy, and would then depart. He once returned of his own accord, and was severely beaten; after that, he knew that he was not supposed to go home until he was fetched.

He worked, all day, alone, eating a communal meal with the women in the evening.

And sleeping alone.

He was bored and lonely.

And hungry.

And puzzled.

He saw old men, who held themselves apart from the rest of the community; there seemed to be about thirty of them, living in the massive stone beehive. But where were the old women? And where were all the people of middle years? Some of the young women were pregnant, but where were their husbands?

For the most part, work appeared to be done by children of both sexes, who began to toil away from the earliest age, and by young women. Togura saw a few young men; he guessed their number at half a dozen in a community of perhaps three hundred people. The young men were always silent and withdrawn; they seemed to be sleep-walking. As far as he could tell, they never spoke.

In the evening, the women talked at Togura readily, but he could never make sense of anything they said. He found it impossible to learn their names; they, for their part, seemed to think that he was concealing his own identity. He named himself first as Togura and then as Togura Poulaan; they memorised that with no trouble at all, but never seemed satisfied with it. His own attempts to come to grips with their half-sung names were disastrous; his efforts provoked frowns, shock, pain, dismay or open contempt. Nobody laughed. These people did not seem to know what laughter was.

Togura came to suspect that these people changed their names according to the time of day, or swapped and traded their names between each other, or identified themselves with one form of a name yet expected to be addressed in an entirely different fashion. He was baffled, frustrated by his failure to unravel the tantalising mystery of their liquid, ever-singing language.

Not that he had all that much time for philological research. For many days, that evening meal was his one link with the rest of humanity; for the rest of the time, he was as solitary as a hermit, enduring the long cold nights spent in his small stone cell, or working alone in his own quadrant of the city.

As the days grew shorter and colder, and the weather grew worse and worse, he did less and less work. Sometimes he spent all day huddled by a tapering fire lit in a mute stone room in the mute stone ruins, listening to a storm howling outside and watching for cracks in the sky.

The numb days of isolation, one much the same as the next, seemed to run together to become one single, endless day. Exiled from all effective community, he began to hallucinate. The stones mumbled to him. His ears sang with high, distant voices. He watched the sky twist into yellow flame then bleed with purple. Trees stirred and shifted at the periphery of his field of vision, though he was never able to actually catch them in the act of walking.

The days hardened into ice. The storms died away, giving him brittle, frosty mornings of absolute silence. He worked hard on those days, for it became a pleasure to see the swift, passionate flames leaping to the sky, to hear the wing-beating roar of the burning as incendiary passions consumed his tangled ivy, and to warm himself by that energy treasured up from the long-gone sun.

Yet, though he worked to the best of his ability, he did not get all that terribly much done. The food was meagre now. He realised that he was very weak. He had boils and chilblains; his gums bled. He feared scurvy.

Once, in a thaw, he inspected his reflection in the waters of the swamp, and did not recognise what he saw. Was this Togura Poulaan, this thing with long hair, dull sunken eyes, a notched nose and vast birds' nest escrescences? How could these thin legs, these cold aching hands, these clog-clad feet, belong to the son of the strong, powerful and well-fleshed Baron Poulaan, that brave, stout-hearted fighting man who commanded all the Warguild?

"I am Togura Poulaan," he said.

But his words carried no conviction. He was no longer certain of his own identity. Who was he then? And what? He was something cold and hungry which lived in a cold, unsmiling place where the people spoke like birds and wind and water. He examined the livid purple scar where the wound on his leg had healed. He tried to remember Cromarty's steel cutting home, but could not focus on his memories. His recollections of people and places seemed blurred, dim, unreal.

Perhaps he had always lived here amidst these ruins in the swamp. Perhaps the whole world without and beyond was nothing more than an idle half-formed fantasy he had conjured into being to give himself some solace in his misery. He tried to dismiss the thought, believing himself, apart from anything else, to be incapable of inventing the language he used to think in, which was certainly not the tongue of the community he now endured.

Nevertheless, his hold on his own identity grew steadily weaker and weaker until, on a day which was suddenly warm, and which startled him with the sight of fresh green growth, he saw one of the old men wearing his jacket.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Wordsmiths and the Warguild»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Wordsmiths and the Warguild» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Wordsmiths and the Warguild» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.