The Iron Thorn

(The first book in the Iron Codex series)

A novel by Caitlin Kittredge

To Howard Phillips Lovecraft ,

who first showed me that strange far place

The moon is dark,

and the gods dance in the night;

there is terror in the sky,

for upon the moon hath sunk an eclipse

foretold in no books of men.

—H. P. LOVECRAFT

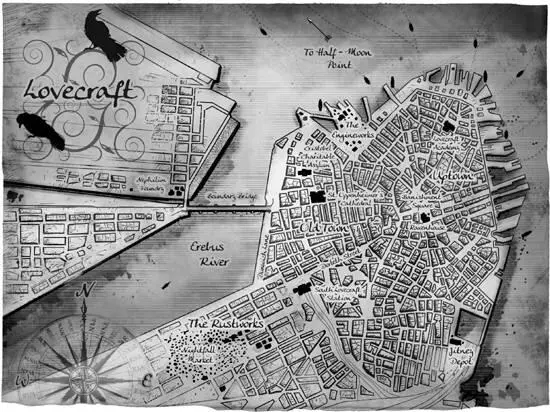

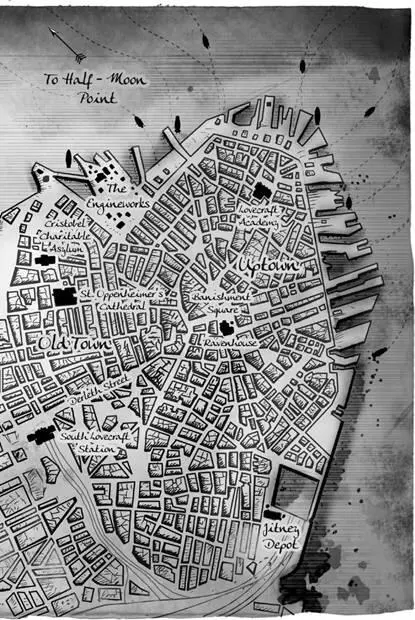

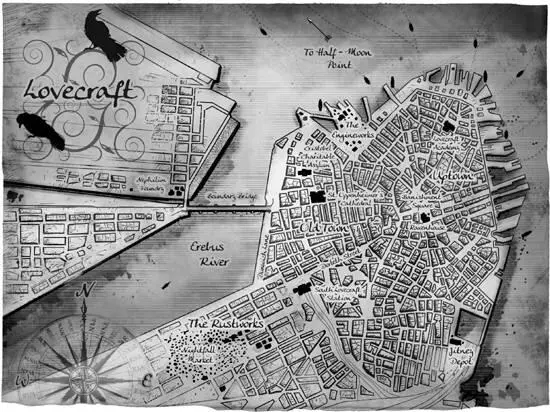

THERE ARE SEVENTEEN madhouses in the city of Lovecraft. I’ve visited all of them.

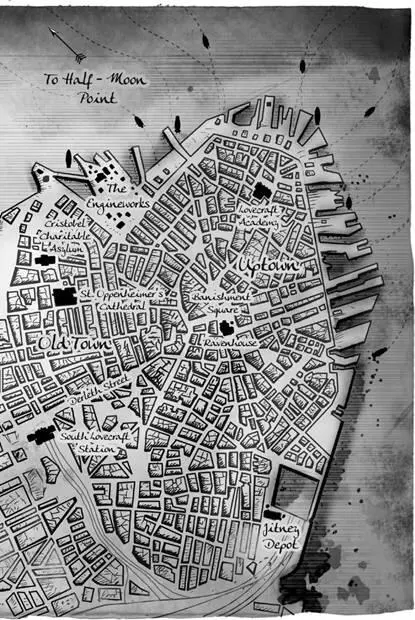

My mother likes to tell me about her dreams when I visit. She sits in the window of the Cristobel Charitable Asylum and strokes the iron bars covering the glass like they are the strings of a harp. “I went to the lily field last night,” she murmurs.

Her dreams are never dreams. They are always journeys, explorations, excavations of her mad mind, or, if her mood is bleak, ominous portents for me to heed.

The smooth brass gears of my chronometer churned past four-thirty and I put it back in my skirt pocket. Soon the asylum would close to visitors and I could go home. The dark came early in October. It’s not safe for a girl to be out walking on her own, in Hallows’ Eve weather.

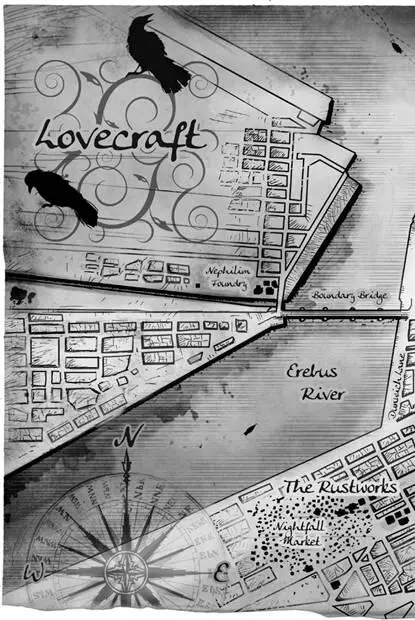

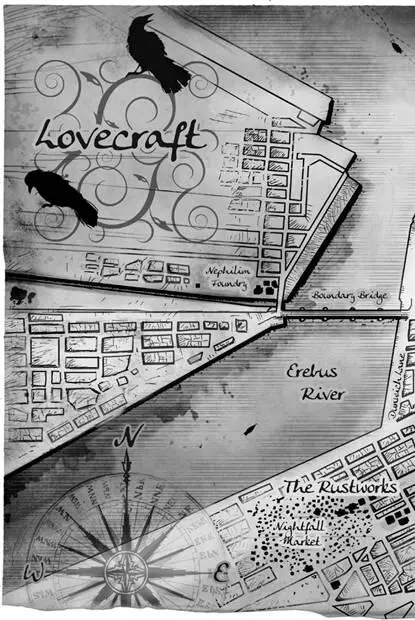

I called it that, the sort of days when the sky was the same color as the smoke from the Nephilim Foundry across the river, and you could taste winter on the back of your tongue.

When I didn’t immediately reply, my mother picked up her hand mirror and threw it at my head. There was no glass in it—hadn’t been for years, at least six madhouses ago. The doctors wrote it into her file, neat and spidery, after she tried to cut her wrists open with the pieces. No mirrors. No glass. Patient is a danger to herself .

“I’m talking to you!” she shouted. “You might not think it’s important, but I went to the lily field! I saw the dead girls move their hands! Open eyes looking up! Up into the world that they so desperately desire!”

It’s a real shame that my mother is mad. She could make a fortune writing sensational novels, those gothics with the cheap covers and breakable spines that Mrs. Fortune, my house marm at the Lovecraft Academy, eats up.

My stomach closed like a fist, but my voice came out soothing. I’ve had practice being soothing, calming. Too much practice. “Nerissa,” I said, because that’s her name and we never address each other as mother and daughter but always as Nerissa and Aoife. “I’m listening to you. But you’re not making any sense.” Just like usual . I left the last part off. She’d only find something else to throw.

I picked up the mirror and ran my thumb over the backing. It was silver, and it had been pretty, once. When I was a child I’d played at being beautiful while my mother sat by the window of Our Lady of Rationality, the first madhouse in my memory, run by Rationalist nuns. Their silent black-clad forms fluttered like specters outside my mother’s cell while they prayed to the Master Builder, the epitome of human reason, for her recovery. All the medical science and logic in the world couldn’t cure my mother, but the nuns tried. And when they failed, she was sent on to another madhouse, where no one prayed for anything.

Nerissa gave a snort, ruffling the ragged fringe above her eyes. “Oh, am I? And what would you know of sense, miss? You and those ironmongers locked away in that dank school, the gears turning and turning to grind your bones …”

I stopped listening. Listen to my mother long enough and you started to believe her. And believing Nerissa broke my heart.

My thumb sank into the depression in the mirror frame, left where an unscrupulous orderly had pried out a ruby, or so my mother said. She accused everyone of everything, sooner or later. I’d been a nightjar, come to drink her blood and steal her life, a ghost, a torturer, a spy. When she turned her rage on me, I gathered my books and left, knowing that we wouldn’t speak again for weeks. On the days when she talked about her dreams, the visits could stretch for hours.

“I went to the lily field …,” my mother whispered, pressing her forehead against the window bars. Her fingers slipped between them to leave ghost marks on the glass.

Time gone by, her dreams fascinated me. The lily field, the dark tower, the maidens fair. She told them over and over, in soft lyrical tones. No other mother told such fanciful bedtime stories. No other mother saw the lands beyond the living, the rational and the iron. Nerissa had been lost in dreams, in one fashion or another, my entire life.

Now each time I visited I hoped she’d wake up from her fog. And each time, I left disappointed. When I graduated from the Lovecraft Academy, I could be too busy to see her at all, with my respectable job and respectable life. Until then, Nerissa needed someone to hear her dreams, and the duty fell to me. I felt the weight of being a dutiful daughter like a stone strapped to my legs.

I picked up my satchel and stood. “I’m going to go home.” The air horn hadn’t sounded the end of hours yet, but I could see the dark drawing in beyond the panes.

Nerissa was up, cat-quick, and wrapping her fingers around my wrist. Her hand was cold, like always, and her nightgown fluttered around her skin-and-bones body. I had always been taller, sturdier than my slight mother. I’d say I took after my father, if I’d ever met him.

“Don’t leave me here,” Nerissa hissed. “Don’t leave me to look into their eyes alone. The dead girls will dance, Aoife, dance on the ashes of the world.…”

She held my wrist, and my gaze, for the longest of breaths. I felt cold creep in around the windowpanes, tickle my exposed skin, run fingers up my spine. A sharp rap came from outside the doors, and we both started. “I know you’re not making trouble for your lovely daughter, Nerissa,” said Dr. Portnoy, the psychiatrist who had my mother’s care.

“No trouble,” I said, stepping away from Nerissa. I didn’t like doctors, didn’t like their hard eyes that dissected a person like my mother, but listening to Portnoy was preferable to listening to my mother shout. I was relieved he’d appeared when he had.

Nerissa’s eyes flickered between me and Portnoy when he stepped into the room. Anxious eyes, filled with animal cleverness. Portnoy patted the breast pocket of his white coat, the silver loop-the-loop of a syringe poking out.

“I’ll kiss you goodbye,” my mother whispered, as if it were our secret, and then she grabbed me in a stiff hug. “See, Doctor?” she shouted. “Just a mother’s love.” She gave a loud laugh, a crow sound, as if it were a colossal joke to be a mother in the first place, and then she backed away from me and sat in the window again, watching the dusk fade to nighttime. I turned my back. I couldn’t stand seeing her for another moment.

“I’m very concerned about your mother,” Dr. Portnoy said. He’d walked me to the end of the ward and had the mountain of an orderly open the folding security gate. “Her delusions are becoming more pronounced. You know if she continues this behavior we’ll have to move her to a secure ward. I can’t risk her infecting the other, trustworthy patients if her madness worsens.”

Читать дальше