“The sky,” the old man whimpered. “The sky !” No more sense could be gotten from him, so they all went up to the roof for a look. Ser Eustace was there before them, standing by the parapets in his bedrobe, staring off into the distance.

The sun was rising in the west.

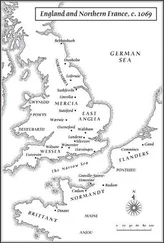

It was a long moment before Dunk realized what that meant. “Wat’s Wood is afire,” he said in a hushed voice. From down at the base of the tower came the sound of Bennis cursing, a stream of such surpassing filth that it might have made Aegon the Unworthy blush. Sam Stoops began to pray.

They were too far away to make out flames, but the red glow engulfed half the western horizon, and above the light the stars were vanishing. The King’s Crown was half gone already, obscured behind a veil of the rising smoke.

Fire and sword, she said.

The fire burned until morning. No one in Standfast slept that night. Before long they could smell the smoke, and see flames dancing in the distance like girls in scarlet skirts. They all wondered if the fire would engulf them. Dunk stood behind the parapets, his eyes burning, watching for riders in the night. “Bennis,” he said, when the brown knight came up, chewing on his sourleaf, “it’s you she wants. Might be you should go.”

“What, run?” he brayed. “On my horse? Might as well try to fly off on one o’ these damned chickens.”

“Then give yourself up. She’ll only slit your nose.”

“I like my nose how it is, lunk. Let her try and take me, we’ll see what gets slit open.” He sat cross-legged with his back against a merlon and took a whetstone from his pouch to sharpen his sword. Ser Eustace stood above him. In low voices, they spoke of how to fight the war. “The Longinch will expect us at the dam,” Dunk heard the old knight say, “so we will burn her crops instead. Fire for fire.” Ser Bennis thought that would be just the thing, only maybe they should put her mill to the torch as well. “It’s six leagues on t’other side o’ the castle, the Longinch won’t be looking for us there. Burn the mill and kill the miller, that’ll cost her dear.”

Egg was listening, too. He coughed, and looked at Dunk with wide white eyes. “Ser, you have to stop them.”

“How?” Dunk asked. The Red Widow will stop them. Her, and that Lucas the Longinch. “They’re only making noise, Egg. It’s that, or piss their breeches. And it’s naught to do with us now.”

Dawn came with hazy gray skies and air that burned the eyes. Dunk meant to make an early start, though after their sleepless night he did not know how far they’d get. He and Egg broke their fast on boiled eggs while Bennis was rousting the others outside for more drill. They are Osgrey men and we are not, he told himself. He ate four of the eggs. Ser Eustace owed him that much, as he saw it. Egg ate two. They washed them down with ale.

“We could go to Fair Isle, ser,” the boy said as they were gathering up their things. “If they’re being raided by the ironmen, Lord Farman might be looking for some swords.”

It was a good thought. “Have you ever been to Fair Isle?”

“No, ser,” Egg said, “but they say it’s fair. Lord Farman’s seat is fair, too. It’s called Faircastle.”

Dunk laughed. “Faircastle it shall be.” He felt as if a great weight had been lifted off his shoulders. “I’ll see to the horses,” he said, when he’d tied his armor up in a bundle, secured with hempen rope. “Go to the roof and get our bedrolls, squire.” The last thing he wanted this morning was another confrontation with the chequy lion. “If you see Ser Eustace, let him be.”

“I will, ser.”

Outside, Bennis had his recruits lined up with their spears and shields, and was trying to teach them to advance in unison. The brown knight paid Dunk not the slightest heed as he crossed the yard. He will lead the whole lot of them to death. The Red Widow could be here any moment. Egg came bursting from the tower door and clattered down the wooden steps with their bedrolls. Above him, Ser Eustace stood stiffly on the balcony, his hands resting on the parapet. When his eyes met Dunk’s his mustache quivered, and he quickly turned away. The air was hazy with blowing smoke.

Bennis had his shield slung across his back, a tall kite shield of unpainted wood, dark with countless layers of old varnish and girded all about with iron. It bore no blazon, only a center bosse that reminded Dunk of some great eye, shut tight. As blind as he is. “How do you mean to fight her?” Dunk asked.

Ser Bennis looked at his soldiers, his mouth running red with sourleaf. “Can’t hold the hill with so few spears. Got to be the tower. We all hole up inside.” He nodded at the door. “Only one way in. Haul up them wooden steps, and there’s no way they can reach us.”

“Until they build some steps of their own. They might bring ropes and grapnels, too, and swarm down on you through the roof. Unless they just stand back with their crossbows and fill you full of quarrels while you’re trying to hold the door.”

The Melons, Beans, and Barleycorns were listening to all they said. All their brave talk had blown away, though there was no breath of wind. They stood clutching their sharpened sticks, looking at Dunk and Bennis and each other.

“This lot won’t do you a lick of good,” Dunk said, with a nod at the ragged Osgrey army. “The Red Widow’s knights will cut them to pieces if you leave them in the open, and their spears won’t be any use inside that tower.”

“They can chuck things off the roof,” said Bennis. “Treb is good at chucking rocks.”

“He could chuck a rock or two, I suppose,” said Dunk, “until one of the Widow’s crossbowmen puts a bolt through him.”

“Ser?” Egg stood beside him. “Ser, if we mean to go, we’d best be gone, in case the Widow comes.”

The boy was right. If we linger, we’ll be trapped here. Yet still Dunk hesitated. “Let them go, Bennis.”

“What, lose our valiant lads?” Bennis looked at the peasants, and brayed laughter. “Don’t you lot be getting any notions,” he warned them. “I’ll gut any man who tries to run.”

“Try, and I’ll gut you.” Dunk drew his sword. “Go home, all of you,” he told the smallfolk. “Go back to your villages, and see if the fire’s spared your homes and crops.”

No one moved. The brown knight stared at him, his mouth working. Dunk ignored him. “Go,” he told the smallfolk once again. It was as if some god had put the word into his mouth. Not the Warrior. Is there a god for fools? “GO!” he said again, roaring it this time. “Take your spears and shields, but go , or you won’t live to see the morrow. Do you want to kiss your wives again? Do you want to hold your children? Go home! Have you all gone deaf?”

They hadn’t. A mad scramble ensued amongst the chickens. Big Rob trod on a hen as he made his dash, and Pate came within half a foot of disemboweling Will Bean when his own spear tripped him up, but off they went, running. The Melons went one way, the Beans another, the Barleycorns a third. Ser Eustace was shouting down at them from above, but no one paid him any mind. They are deaf to him at least, Dunk thought.

By the time the old knight emerged from his tower and came scrambling down the steps, only Dunk and Egg and Bennis remained among the chickens. “Come back,” Ser Eustace shouted at his fast-fleeing host. “You do not have my leave to go. You do not have my leave!”

“No use, m’lord,” said Bennis. “They’re gone.”

Ser Eustace rounded on Dunk, his mustache quivering with rage. “You had no right to send them away. No right! I told them not to go, I forbade it. I forbade you to dismiss them.”

Читать дальше