He couldn’t. The leg that had been pinned beneath the horse had sunk into the clay of the river’s bottom. He was trapped there, with the surface less than a foot away.

He almost laughed. It was inconceivable that he had escaped an entire army of Canim, survived that deadly, bloody lightning, only to drown.

He forced himself not to thrash in panic and instead reached down, digging his fingers into the clay. It had been softened by the water, or the task would have been hopeless, but Tavi was able to work his knee lose, and from there to pull the rest of his leg from the cold grasp of the river’s bottom.

Tavi rose from the river, looked wildly around him, and saw the standard lying half out of the water. He sloshed to the river shore and seized it up, taking it in a fighting grip, and looking up to face twenty or more of the ritualist acolytes, in their black cloaks and mantles of human skin. They had fallen upon the horse as it came from the water, and now their claws and fangs were scarlet with new blood.

Tavi looked back to his left, and saw that the Aleran cavalry was already on the move over the Elinarch. It would be a futile gesture. By the time they arrived, there would be nothing of Tavi left to rescue.

Strange, that it was so quiet, Tavi thought. He saw his death in the eyes of the bloody Canim. It seemed that such a thing should have been a great deal noisier. But he heard nothing. Not his enemies snarls, nor the cries from the city. Not the gurgle of water as the Tiber flowed around his knees. Not even the sound of his own labored breath or the beating of his heart. It was perfectly silent. Almost peaceful.

Tavi gripped the standard and faced the oncoming Canim without moving. If he was to die, it would be on his feet, against them, and he would take as many of the things with him as he possibly could.

Today, he thought, I am a legionare.

The fear vanished, and Tavi abruptly threw back his head and laughed. “Come on!” he shouted to them. “What are you waiting for? The water’s fine!*’

The Canim rushed at him-and then suddenly slid to a halt in their tracks with two dozen panicked, inhuman stares.

Tavi blinked, entirely confused. Then he looked behind him.

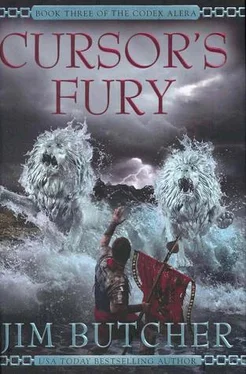

On either side of him, the waters of the Tiber had flowed into solid form, into water-sculptures similar to those he had seen before.

Similar, but not the same.

Two lions, lions the size of horses, stood at his sides, their eyes flickering with green-blue fox fire. Though formed of water, every detail was perfect, down to the fur, down to the battle scars upon their powerful chests and shoulders. Stunned, Tavi lifted a hand and touched one of the beasts on its flank, and though its substance appeared to be liquid, it was as hard as stone beneath Tavi’s fingers.

Tavi turned to face the Canim again, and as he did so both lions opened their mouths and let out roars. Tavi could not hear it, but it set his armor to buzzing, and the surface of the waters rippled and jumped in place for a hundred feet in every direction.

The Canim flinched away from the river, and their stance changed, becoming wary, their eyes apprehensive. And then, almost as one, they turned and fled over the grass, back toward the Canim host.

Tavi watched them go, then slogged up out of the river and planted the standard’s butt on the ground. He leaned wearily against it and turned his head to consider the enormous furies that had risen to his defense.

A faint tremble in the earth warned him of approaching horses, and he looked up to find Max and Crassus thundering up to him on horses of their own. Each of the young legionares dismounted and came toward him. Max’s mouth started moving, but Tavi shook his head, and said, “I can’t hear anything.”

Max scowled at him. Then he turned to the larger of the two water furies. The great old lion greeted Max and nuzzled his hand as affectionately as a pet cat. Max placed his hand on the fury’s muzzle and nodded, the gesture both grateful and dismissive, and the fury sank back into the river.

Beside him, Crassus went through almost precisely the same routine, and the second water lion also sank from sight. The half brothers stood in their place for a moment, staring at one another. Neither of them spoke. Then Crassus flushed and shrugged. Max opened his mouth and let out a bark of the laughter Tavi was familiar with, then shook his had, punched his brother lightly on the shoulder, and turned to Tavi.

Max faced him and mouthed, words exaggerated so that Tavi could read them, That was not in the plan.

“He read my bluff,” Tavi said. “But I made him look pretty bad. It might have worked.”

Max mouthed, This it what it looks like when it works? You are insane.

“Thank you,” Tavi said. He tried to sound dry.

Max nodded. How had is your leg?

Tavi frowned at him, puzzled, and looked down. He felt startled to find, high on his left thigh, a wide, wet stain of fresh blood on his breeks. He touched his leg tentatively, but felt no pain. He hadn’t been injured there. The fabric wasn’t even torn.

Then an inspiration hit him, and he reached into his pocket. At the very bottom, precisely at the top of the bloodstain, Tavi found it-the scarlet stone he’d stolen from Lady Antillus. It felt oddly warm, almost uncomfortably so.

“I’m fine,” Tavi said. “I don’t think that’s mine.” He frowned down, and then peered out at the Canim host, and then at the scarlet clouds overhead.

You need not fear his breed’s power, and you know it, Kalarus had told Lady Antillus. And then immediately after, he had ordered her to fly to Kalare. But if she could have flown, why would she steal horses?

Because the stone would have protected her from the Canim ritual sorcery that blanketed the skies.

Just as it had protected Tavi from the same power.

His heart beat faster. He tried to think of another explanation, but it was the only thing that made sense. How else could he have survived a blast of the same power that had slain the Legion’s officers?

Of course. The Canim had known precisely where to strike. Legion commanders kept their tents in the same location in any camp, no matter where they went. No one was supposed to have survived that blast-no one but Lady Antillus, who would have had the stone with her had not Tavi stolen it when he took her purse.

The original treason became clear to Tavi. After assuming command of the Legion according to proper chain of command, Lady Antillus was probably supposed to lead the union in a retreat, so that the Canim could control the bridge, thereby preventing any sort of Aleran incursion from the north that could march through to Kalarus’s lands.

Of course, that had been before she knew the Canim were arriving in such enormous numbers. Kalarus had tried to use them as a weapon, but they had turned and sliced into his own hand.

Hey, Max mouthed, sticking his face into Tavi’s. Are you all right?

Max and Crassus suddenly whipped their heads toward the Canim host, then they both started back for their horses. Max mouthed to Tavi, They’re coming. We need to go.

Tavi grimaced, nodded, then took the standard and mounted behind Max. The three of them rode for the town as the Canim host began to stir once more. Out of sheer defiance, Tavi raised the standard and let the wind of their passage send the blackened eagle flying where anyone with eyes could see.

Tavi couldn’t hear it as they rode back through the town’s gates, but as they closed behind them he looked up at the battlements and around the courtyard in surprise. Every man in sight, fish and veteran alike, pale-eyed northmen and dark-eyed southerners, old, young, Knight, centurion, and legionare all stood facing Tavi, slamming their steel-cased fists to their breastplates in what had to be a deafening thunder as together they shouted and cheered their captain’s return.

Читать дальше