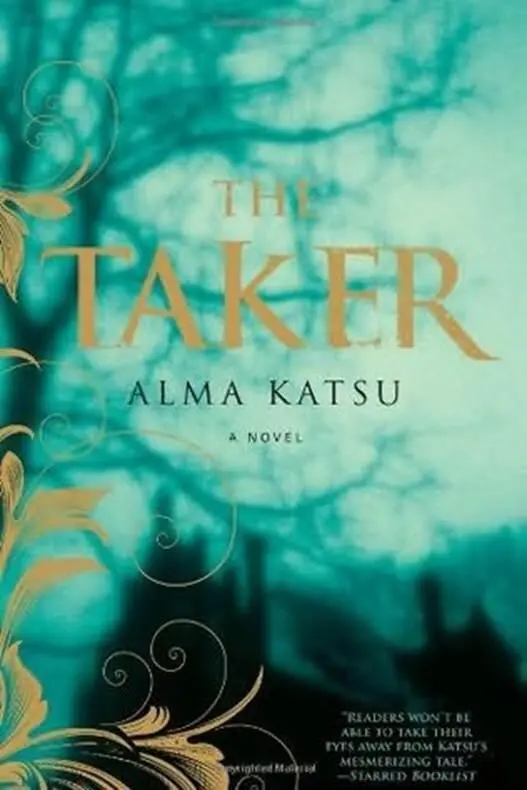

The first book in the Taker series, 2011

As The Taker is a work of fantasy, I don’t imagine readers come to it expecting historical authenticity, but there is one liberty I’ve taken with history that must be pointed out. While there is no town of St. Andrew in the state of Maine, if the reader attempts to triangulate the fictional village’s location based on clues in the text, you’ll see that if it were to exist, it would fall about where the town of Allagash stands today. Truth be told, this exact area of Maine wasn’t settled until the 1860s. However, the Acadian town of Madawaska, not far away, was settled in 1785, and so in my mind it didn’t seem too much of a stretch to have Charles St. Andrew found his outpost around this time.

Goddamned freezing cold. Luke Findley’s breath hangs in the air, nearly a solid thing shaped like a frozen wasp’s nest, wrung of all its oxygen. His hands are heavy on the steering wheel; he is groggy, having woken just in time to make the drive to the hospital for the night shift. The snow-covered fields to either side of the road are ghostly sweeps of blue in the moonlight, the blue of lips about to go numb from hypothermia. The snow is so deep it covers all traces of the stumps of stalks and brambles that normally choke the fields, and gives the land a deceptively calm appearance. He often wonders why his neighbors remain in this northernmost corner of Maine. It’s lonely and frigid, a tough place to farm. Winter reigns half the year, snow piles to the windowsills, and a serious biting cold whips over the empty potato fields.

Occasionally, someone does freeze solid, and because Luke is one of the few doctors in the area, he’s seen a number of them. A drunk (and there is no shortage of them in St. Andrew) falls asleep against a snowbank and by morning has become a human Popsicle. A boy, skating on the Allagash River, plunges through a weak spot in the ice. Sometimes the body is discovered halfway to Canada, at the junction where the Allagash meets up with the St. John. A hunter goes snow blind and can’t make his way out of the Great North Woods, his body found sitting with its back against a stump, shotgun lying uselessly across his lap.

That weren’t no accident , Joe Duchesne, the sheriff, told Luke in disgust when the hunter’s body was brought to the hospital. Old Ollie Ostergaard, he wanted to die. That’s just his way of committing suicide. But Luke suspects if this were true, Ostergaard would have shot himself in the head. Hypothermia is a slow way to go, plenty of time to think better of it.

Luke eases his truck into an empty parking space at the Aroostook County Hospital, cuts the engine, and promises himself, again, that he is going to get out of St. Andrew. He just has to sell his parents’ farm and then he is going to move, even if he’s not sure where. Luke sighs from habit, yanks the keys out of the ignition, and heads to the entrance to the emergency room.

The duty nurse nods as Luke walks in, pulling off his gloves. He hangs up his parka in the tiny doctors’ lounge and returns to the admitting area. Judy says, “Joe called. He’s bringing in a disorderly he wants you to look at. Should be here any minute.”

“Trucker?” When there is trouble, usually it involves one of the drivers for the logging companies. They are notorious for getting drunk and picking fights at the Blue Moon.

“No.” Judy is absorbed in something she’s doing on the computer. Light from the monitor glints off her bifocals.

Luke clears his throat for her attention. “Who is it then? Someone local?” Luke is tired of patching up his neighbors. It seems only fighters, drinkers, and misfits can tolerate the hard-bitten town.

Judy looks up from the monitor, fist planted on her hip. “No. A woman. And not from around here, either.”

That is unusual. Women are rarely brought in by the police except when they’re the victim. Occasionally a local wife will be brought in after a brawl with her husband, or in the summer, a female tourist may get out of hand at the Blue Moon. But this time of year, there’s not a tourist to be found.

Something different to look forward to tonight. He picks up a chart. “Okay. What else we got?” He half-listens as Judy runs down the activity from the previous shift. It was a fairly busy evening but right now, ten P.M., it’s quiet. Luke goes back to the lounge to wait for the sheriff. He can’t endure another update of Judy’s daughter’s impending wedding, an endless lecture on the cost of bridal gowns, caterers, florists. Tell her to elope , Luke said to Judy once, and she looked at him as though he’d professed to being a member of a terrorist organization. A girl’s wedding is the most important day of her life , Judy scoffed in reply. You don’t have a romantic bone in your body. No wonder Tricia divorced you. He has stopped retorting, Tricia didn’t divorce me, I divorced her , because nobody listens anymore.

Luke sits on the battered couch in the lounge and tries to distract himself with a Sudoku puzzle. He thinks instead of the drive to the hospital that evening, the houses he passed on the lonely roads, solitary lights burning into the night. What do people do, stuck inside their houses for long hours during the winter evenings? As the town doctor, there are no secrets kept from Luke. He knows all the vices: who beats his wife; who gets heavy-handed with his children; who drinks and ends up putting his truck into a snowbank; who is chronically depressed from another bad year for the crops and no prospects on the horizon. The woods of St. Andrew are thick and dark with secrets. It reminds Luke of why he wants to get away from this town; he’s tired of knowing their secrets and of them knowing his.

Then there is the other thing, the thing he thinks about every time he steps into the hospital lately. It hasn’t been so long since his mother died and he recalls vividly the night they moved her to the ward euphemistically called “the hospice,” the rooms for patients whose ends are too close to warrant moving them to the rehab center in Fort Kent. Her heart function had dropped below 10 percent and she fought for every breath, even wearing an oxygen mask. He sat with her that night, alone, because it was late and her other visitors had gone home. When she went into arrest for the last time, he was holding her hand. She was exhausted by then and stirred only a little, then her grip went slack and she slipped away as quietly as sunset falling into dusk. The patient monitor sounded its alarm at nearly the same time the duty nurse rushed in, but Luke hit the switch and waved off the nurse without even thinking. He took the stethoscope from around his neck and checked her pulse and breathing. She was gone.

The duty nurse asked if he wanted a minute alone and he said yes. Most of the week had been spent in intensive care with his mother, and it seemed inconceivable that he could just walk away now. So he sat at her bedside and stared at nothing, certainly not at the body, and tried to think of what he had to do next. Call the relatives; they were all farmers living in the southern part of the county… Call Father Lymon over at the Catholic church Luke couldn’t bring himself to attend… Pick out a coffin… So many details required his attention. He knew what needed to be done because he’d been through it all just seven months earlier when his father died, but the thought of going through this again was just exhausting. It was at times like these that he most missed his ex-wife. Tricia, a nurse, had been good to have around during difficult times. She wasn’t one to lose her head, practical even in the face of grief.

Читать дальше