David Farland

Nightingale

To Mary and Spencer for their continued help and support.

Buddy Bracken, who took me and my son Forrest on a night tour of the swamps at Black River in the Louisiana Bayou;

Christy Hall, who was so kind as to give me the guided tours of Tuacahn High School as I prepared for this novel;

Danielle Wolverton, who provided insights into Tuacahn High School along with editorial support;

Joshua Essoe for providing a fine edit;

Miles Romney and all of his team for their work in illustrating, and composing for the enhanced novel.

A number of people gave excellent critical help, and I'd like to thank all of my readers. It's difficult to express just how grateful I really feel to all of you, especially Day Leclaire, romance author, whose insights into plotting were invaluable. I also got wonderfully detailed feedback from Gray Rinehart, editor at Orson Scott Card's Intergalactic Medicine Show Magazine, who has an uncanny ability to spot every kind of typo imaginable.

There are so many people who offered valuable comments. Very often, something as simple as "I felt like this" allows an author to get a better handle on a reader's emotional response, and that's a tremendous help. I can't get into much detail, but let me just mention a few: Sabine Berlin, Heather Clark, Lisa Devers, Jared Garrett, John Harper, David Hill, Jennifer D. Lerud, Juliana Montgomery, Joe Romano, and Robin Weeks.

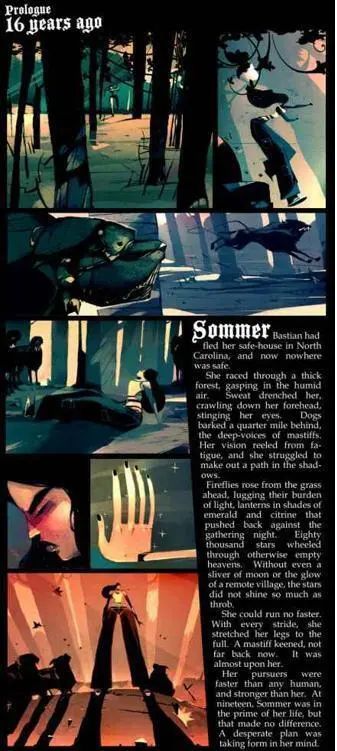

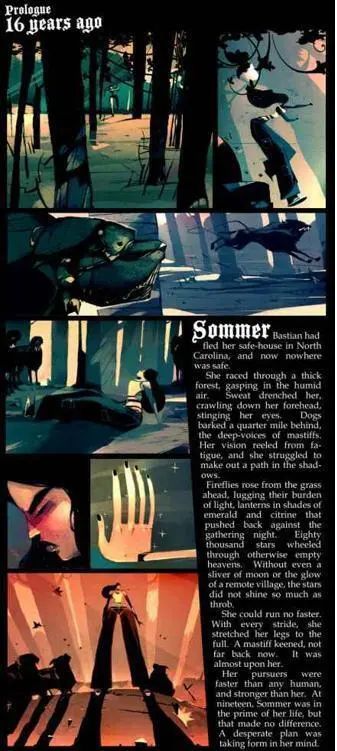

Sommer Bastian had fled her safe house in North Carolina, and now nowhere was safe.

She raced through a thick forest, gasping in the humid air. Sweat drenched her, crawling down her forehead, stinging her eyes. Dogs barked a quarter mile behind, the deep-voices of mastiffs. Her vision reeled from fatigue, and she struggled to make out a path in the shadows.

Fireflies rose from the grass ahead, lugging their burden of light, lanterns in shades of emerald and citrine that pushed back against the gathering night. Eighty thousand stars wheeled through otherwise empty heavens. Without even a sliver of moon or the glow of a remote village, the stars did not shine so much as throb.

She could run no faster. With every stride, Sommer stretched her legs to the full. A mastiff keened, not far back now. It was almost upon her.

Her pursuers were faster than any human, and stronger than her. At nineteen, Sommer was in the prime of her life, but that made no difference. A desperate plan was taking form in her mind.

The dogs were trained to kill. But she knew that even a trained dog can't attack someone who surrenders. Nature won't allow it. And when a dog surrenders completely, it does so by offering its throat.

That would be her last resort—to lie on her back and give her throat to these killers, so that she could draw them in close.

She raced for her life. To her right, a buck snorted in the darkness and bounded away, invisible in the night. She hoped that its pounding would attract the dogs, and they did fall silent in confusion, but soon snarled and doubled their speed.

The brush grew thick ahead—blackberries and morning glory crisscrossing the deer trail. She heard dogs lunging behind her; one barked. They were nearly on her.

Sommer's foot caught on something hard—a tough tree root—and she went sprawling. A dog growled and leapt. Sommer rolled to her back and arched her neck, offering her throat.

Three dogs quickly surrounded her, ominous black shadows that growled and barked, baring their fangs, sharp splinters of white. They were huge, these mastiffs, with spiked collars at their throats, and leather masks over their faces. Their hooded eyes seemed to be empty sockets in their skulls.

They bounded back and forth in their excitement, shadowy dancers, searching for an excuse to kill.

I can still get away , Sommer thought, raising a hand to the air, as if to block her throat. By instinct she extended her sizraels—oblong suction cups that now began to surface near the tip of each thumb and finger. Each finger held one, an oval callus that kept stretching, growing.

Though she wasn't touching any of the dogs, at ten feet they were close enough for her to attack.

She reached out with her mind, tried to calm herself as she focused, and electricity crackled at the tips of her fingers. Tiny blue lights blossomed and floated in the air near her fingers like dandelion down. The lights were soft and pulsing, no brighter than the static raised when she stroked a silk sheet in the hours before a summer storm.

She entered the mastiffs' minds and began to search. They were supposed to hold her until the hunters came, maul her if she tried to escape. Their masters had trained the dogs well.

But a dog's memories were not like human memories, thick and substantial.

Sommer drew all of the memories to the surface—hundreds of hours of training, all bundled into a tangle—and snapped them, as if passing her hand through a spider's web.

Immediately all three mastiffs began to look around nervously. One lay down at her feet and whimpered, as if afraid she might be angry.

"Good dogs," Sommer whispered, tears of relief rising to her eyes. "Good!" She rolled to her knees, felt her stomach muscles bunch and quaver. She prepared to run.

"Where do you think you're going?" a deep voice asked.

There are more dangerous things than mastiffs, Sommer knew. Of all the creatures in the world, the man who spoke now was at the top of the list.

She turned slowly. A shadow loomed on the trail behind her. In the starlight, she could make out vague features. She knew the man well. He was handsome—not as in "pleasing to look at," but so handsome that it made a woman's heart pound. His beauty, the clean lines of his jaw, the thoughtful look to his brow, hit her like a punch to the chest even now, though she knew he was a killer.

His name was Adel Todesfall, and he served as the head of security for the man who had held her captive for most of the past year, Lucius Chenzhenko.

"Don't hurt me," Sommer's hand raised protectively. "Please don't hurt me. Tell Lucius that I'll be his poppet. I'll be his toy. I'll do anything."

Adel drew a gleaming piece of metal from a shoulder holster, a pistol. Sommer was powerful in her way. Even at ten feet she presented a danger, but Adel remained outside her range.

"You're ill-suited to be a poppet," Adel argued. "Nor would you be very entertaining as a toy. Besides, we have a problem here, one not so easily solved. You stole something from him...."

She peered up, bewildered. "No," she begged. "I took nothing from the compound, not even spare clothes."

Adel smiled, amused. "You don't remember?" She shook her head. "You don't recall carrying a child in your womb for these past eleven months?"

"I've never—" had a child , she thought. But she remembered Lucius, that sadistic monster, forcing himself upon her....

Sommer's people, the masaaks, took longer to gestate than humans did. Sommer could not imagine having carried a child to term, much less forgetting about it, unless...

Adel offered, "You've had the memory ripped from you."

"I don't recall having a child!" she said. She hoped to stall while she gathered her wits. Sommer could not reveal information that she didn't know. Yet if another memory thief had pulled vital information from her, Sommer knew that they might not have been thorough. Each memory in a person's brain is laid down tens of thousands of times, through multiple connections between neurons. Stray thoughts, random feelings, might still be hiding in her skull—clues to the mystery of her missing child.

Читать дальше