“To talk,” said Damon with a faint shrug. “It is customary, in the lowlands.”

Sasha nodded. In Lenayin, individual warriors might talk before a duel, but rarely entire armies. She did not think that most Lenay warriors would disapprove of the notion, however. To discuss protocols with a man you were about to kill seemed honourable. Oddly, she found herself wondering why Lenays had never adopted the custom for grand battles. Probably, she thought, because there was so little flat ground in Lenayin. Armies did not line up, but struck with the first advantage. An odd case of terrain dictating custom, perhaps.

From the top of the slope near the castle, a small party of men rode forth. Sasha squinted, but could not make out the flags. Sweat prickled on her brow. She thought she knew why she had been asked for. She wanted to say no. To plead off sick, or find some lameness in her horse. But she could not appear weak before the men. And if her horse was lame, they’d find her another.

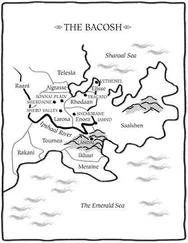

“It must be them,” Koenyg concluded as the party kept coming. The king tapped heels to his horse, and rode with his three children toward the stream and the slope beyond. The stream barely came up to the horses’ knees, and soon they were cantering across fields as the ground began to rise. There were three in the oncoming party, two human and one serrin. Sasha nearly turned back.

Koenyg signalled to her and Damon, and Sasha moved up on Koenyg’s side, the far left position in their line. Damon took the far right, beside their father. They came to a trot, and then a halt, perhaps ten strides from the opposing line of three.

“I’m General Rochan,” said the central man, in Torovan. He wore a helm with a general’s crest, and wore chest and shoulder guards over mail. A middle-sized man, with intense, close-set eyes, of perhaps forty summers. “Commander of the Enoran Second Regiment, acting Commander of Armies for this engagement. To my left is my second, Formation Captain Lashel. To my right, Vilan, of the talmaad .”

Sasha forced herself to look. The serrin had pure white hair like Rhillian’s, worn long and untidy. His eyes were nearly gold within a pale face. It gave him the look of an albino, but Sasha doubted that he was. He was simply serrin. Sasha wished he were elsewhere.

“King Torvaal Lenayin,” her father replied grimly. “My sons, Koenyg and Damon. My daughter, Sashandra.”

General Rochan looked across their line with his sharp eyes. Something about his manner disturbed Sasha further. She had hoped that perhaps some turmoil of Enoran politics would lead the Enorans to place an incapable general in command of this battle. To observe the thoughts racing through Rochan’s eyes, she did not think that had happened.

“You come a long way, King of Lenayin,” Rochan said finally. He drew himself up, and his gaze held little of respect or fear. “Why are you here? We Enorans have done nothing to you.”

“You sin against the Verenthane faith,” said Torvaal. “You hold lands that are not yours.”

“Truly?” Rochan looked genuinely astonished. “I can trace my ancestry back a dozen generations on this land. How is this land not mine?”

“You sin against the Verenthane faith,” Torvaal replied, as though he had not heard the general. “The Archbishop of Torovan has decreed it.”

“Ah,” said Rochan. “Torovan. And how many have the Torovans sent you? It looks perhaps fifteen thousand from our vantage? Eighteen, at the most? They had promised you thirty, had they not? Why does the Archbishop of Torovan send Lenays to die for his cause?”

“Any Verenthane would serve as well,” said Torvaal darkly.

“And barely half of you are Verenthane,” said Rochan, giving Sasha a long stare. Sasha looked at the slope behind him, and the castle, large against the sky.

“We have not ridden all this way to debate,” Koenyg interrupted. “State your terms, if you have any, or offer your surrender. Should you offer it, you shall be given honourable terms from Lenayin.”

Rochan snorted and smiled unpleasantly. “This from a Lenay, who finds nothing honourable in surrender. Have no fear, Prince of Lenayin, we like it as little as you do. Your allies have made it plain for two hundred years that they shall offer no terms. We think it preferable to die on our feet with a sword in our hands than at the end of a Larosan rope, or beneath their torture knives.”

Sasha barely repressed a shudder. The serrin Vilan noticed. Again, Sasha looked away, hoping it would all end soon. Battle would be preferable to this. In battle, one did not have to think.

“Do you have terms?” Koenyg repeated.

“Withdraw now,” said Rochan, coldly. “Those are my terms. You are foreigners to this kind of warfare. Know that the Enoran Steel has faced armies twice the size of what confronts us here, and left them barely a man alive. I think it an abomination that Lenayin’s rulers should lead its sons to die by the thousand upon this foreign field, for this most ignoble cause. You are a curse upon your people, sirs. They will curse you when we are done.”

“The wounded and surrendering shall not be harmed,” said Torvaal, as though he had not heard. “Whatever your previous opponents may have practised, we Lenays practise honourable warfare. Prisoners shall not be tortured, and shall be returned to their families upon the reaching of terms. Neither do we ransom for gold, nor otherwise partake in hostages, as is the frequent custom here. There is no honour in gold. Submission, by death or surrender, is all that honour requires.”

Rochan frowned, and was silent for a moment, considering that. Then he nodded. “I accept these terms,” he said, less coldly than before. “We shall reciprocate, when you are defeated.”

“I hear you have not in the past,” Koenyg accused him.

“No,” the general admitted. “Two centuries of dishonourable warfare by our opponents put a stop to it. Ask of your allies of our captured soldiers tortured and disembowelled alive. Ask them what worse things they do to captured serrin. Our captured enemies we attempt to rehabilitate. Some refuse and prefer death. Others are sent to Saalshen. Others still have come to recognise the error of their ways. Formation Captain Lashel here was once a knight of Merraine. Now, he fights for us, by choice.”

Koenyg seemed astonished. He stared at the captain, who nodded, and said nothing. Sasha felt that she might be ill.

“Sashandra,” said the serrin Vilan. He leaned forward on his saddlehorn, gazing at her with those impossible golden eyes. “You are troubled, Sashandra,” he said in Saalsi. His voice was gentle. “You have the look of one lost, and struggling to recognise the path upon which you walk. It seems familiar to you in parts, but then it plunges into foreign mists. You struggle on, more and more certain that you are lost, only to recognise a tree, or a rock, or to think you recognise them. Surely your path is correct. Surely it is true. Is it not?”

Serrin verbs played games through the undergrowth of Saalsi grammar, twisting about to ambush entire sentences unawares. Sasha stared at him, helplessly. She opened her mouth to speak, but nothing came out. Her family all frowned at her, wondering what was said. The Enorans also frowned, but their eyes were comprehending.

“Can you truly fight us, Sashandra?” Vilan asked as though he knew her personally. “Have we caused you such pain in your heart?” A shiver flushed her skin. And she recalled abruptly the battlefield before the walls of Ymoth, and Errollyn talking with her of the Synnich, and of how he, Aisha, Terel and Tassi had known how to come to Lenayin, despite word of the impending battle being a two-month round trip away.

Dear spirits, she realised in horror, she’d never asked him how. And he’d never told her, perhaps sensing that she did not truly wish to know, lest she discover something that would shake her world. Vilan now looked at her as though he knew her, and somehow, she did not doubt that he did. What was the vel’ennar truly? And if Errollyn lacked it, being du’jannah , how had he known to come to Lenayin when he had? And why had she never asked him how?

Читать дальше