The angry priest seemed to take a breath, eyes darting, as he reassessed his situation. Clearly it had not occurred to anyone, in organising this ceremony, that something like this might happen.

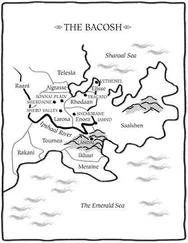

“That is the Shereldin Star,” he explained. “It is the founding star of the Enoran High Temple, the holiest temple in all Verenthane lands, the place where the gods did pass down the Scrolls of Ulessis to Saint Tristen, and to all human kind. It is surely most blessed by the gods, and should you not kneel before their audience, then you do blaspheme most grievously to their very faces!”

“I see no gods here,” said Sasha. “Only men. Any god who would demand that a Lenay man kneel to a golden trinket is no true god of Lenays.”

“You must kneel!” the priest yelled, tendons straining in his neck.

Sasha just stared at him, contemptuously.

“We Lenays,” Jaryd said loudly, “have very stiff knees.” There was laughter from Lenays about the courtyard. More rose to their feet, even the lords. To blaspheme was one thing, but even for devout Verenthanes, this was now about far more than faith.

Behind the priest, a dark-cloaked figure came walking. To Sasha’s astonishment, it was her father, solemn and unsmiling as always. He stopped beside the priest.

“It was a mistake,” he told the priest, in Torovan, “to hold this ceremony before the Goeren-yai. I would have told you that this would happen, but I was not consulted. That oversight now leaves us in an unfortunate predicament.”

“This is your daughter,” said the priest. “Make her obey.”

“She is Goeren-yai,” the king said simply, “and I cannot.”

The priest stared at him. Sasha stared too, in greater shock than the priest. Her father had admitted the unsayable. She had lived much of her life in fear of what might happen should she state the fact so publicly. Now, her father did it for her, in front of a lowlands priest and his flock.

“Your Highness,” said the priest, between gritted teeth, “Lenayin must decide whether it is a Verenthane kingdom or not. The moment for deciding is now.”

“In Lenayin,” said the king, “the chasm between what the kingdom is, and what its nobility may aspire to make it, is often vast indeed. I urge you not to press this matter. I know my people. A Lenay will bow only to whom he chooses, and should you seek to deny him that right, then this alliance is ended, and the holy lands shall remain in the hands of Saalshen. Worse, I think it likely this courtyard shall be drowned with holy blood. I urge you to consider your priorities, Father.”

Torvaal Lenayin did not look at his daughter. He had not spoken with her since her return to the Lenay fold. Word was that he grieved for Alythia. Sasha had wondered if he blamed her and decided that she did not care what he thought. But now, she wondered again.

The priest stormed back toward the archbishop.

“Father,” said Sasha. And felt a sudden, inexplicable yearning. For what, she did not know. “Father…”

Torvaal Lenayin turned on his heel and followed the priest, his black cloak flowing out behind. Sasha felt a pain in her throat. She wanted to run after him and grab him by the arms, and yell into his face. But she did not know what she would say.

There was dark, earnest discussion between priests, Archbishop Turen, King Torvaal and Regent Arosh. They took their places again, and the command was given to rise. The ceremony resumed with all now standing. Sasha could not see much over the tall heads of the men around her, but she did not care. Bacosh men standing nearby gave her very dark looks, but Jaryd and Yasmyn kept guard of her flanks. She could not see Sofy, nor her brothers, from this position, but she could see the Black Order, pointed hoods in rows, like sharp black teeth before the temple steps.

Sasha trained with the officers and yuans that Damon had selected, discussing tactics, and the new use to which Lenay warriors were being instructed to put their shields. There were even several knights, one from Merraine, the other from Tournea, adding their expertise at Damon’s request. They discussed, demonstrated, and made small formations on the riverbank a little upstream from the Nithele walls. Even here, Lenay soldiers intruded upon their practice, filling pots with water, leading horses to drink, bathing, or bartering with the boats that rowed upstream from the city. Those were everywhere, a mass of narrow vessels hugging the shore where the high waters moved with less force, men aboard shouting their wares to all ashore. In others, city girls lifted their dresses to show pale legs, as men ashore hollered and laughed, and asked after the price.

“Perhaps if our cavalry cannot win through the Steel lines,” one powerful yuan said at a pause in training, “we could send our army of whores at them.”

Men laughed. There were hundreds trailing the Army of Lenayin, it was said, though Sasha had not visited the tail of the column to see. Many had children with them, and some, husbands. It was even said that parents were offering daughters for a price. Sasha was astonished at the utter pridelessness of the Bacosh peasantry. She had never considered that a people might discard their honour so wantonly. Perhaps, it occurred to her, honour was not a necessity of human life, but rather a luxury. Her Lenay soul rebelled at the thought.

Mostly she watched as the men discussed and considered the battle to come, contributing occasionally, but not joining in directly. This was men’s fighting, with heavy armour and heavy blows, and no room for finesse. Svaalverd technique counted for little in such an environment. Without technique, she would be just a woman surrounded by men, and no use to anyone. Ahorse, however, she fancied she might have a contribution to make.

One of the young men present was a new arrival, from Torovan. Duke Carlito Rochel, the Lord of Pazira province, son of Sasha’s old friend Alexanda Rochel. He had ridden in with the advance party bearing the Shereldin Star, and said now that the main Torovan column was but two days’ march behind. Sasha was pleased to meet Carlito, yet sad too, for his father had tried his best to prevent Pazira’s participation in this war. He would be very sad to know that his son now rode to fight in the greatest battle the Bacosh had ever known. Sasha wondered if Alexanda had died in vain. And wondered if she would ever again see a day where every new thought did not make her sad.

As she sat on a riverside log, watching the men discussing the collision of two shield lines, she heard a rattle of armoured footsteps. A knight approached, in neck-to-ankles chain mail, and carrying a sack.

“Sashandra Lenayin!” he called, as though pleased to see her. Sasha stood up. Over the mail, the knight wore a surcoat of family colours that Sasha did not recognise. Four more knights walked with him, and there was something to their manner that she did not like. Sasha heard the discussion and clash of practice stanch on shield behind her cease.

The man before her was broad and dark haired. “Aren’t you going to ask who I am?” he asked her after a pause.

“If I cared, I’d ask,” said Sasha.

“I am Sir Eskwith, Lord of Assineth. Cousin to the prince regent. Your relation, I suppose.”

“Great,” said Sasha, expressionlessly. “Welcome to the family.”

“I saw your little performance today, before the temple,” Eskwith continued. “It has caused many of the good lords to wonder exactly whose side you’re on.”

“Lenayin’s,” said Sasha, with certainty.

“Pagan Lenayin’s,” said Sir Eskwith.

“Lowlanders make that distinction. Lenays don’t.”

“My new friends in the Lenay north certainly do.”

“I’ve killed plenty,” said Sasha. “I don’t care what they think.” She could hear her friends approaching, wondering at the intrusion on the Lenay camp.

Читать дальше