Sofy shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“Then you don’t love him.”

Sofy opened her mouth to protest, but realised that Sasha’s conclusion was obvious. “I barely know him,” she said instead.

“But he’s good in bed,” Sasha persisted. Sofy frowned at her. “And tall and handsome. I hear the talk.”

“He is very tall and handsome,” Sofy agreed, still frowning. “But I’m not a naive little girl any more, Sasha. Tall and handsome is not why I married him.”

“Do you hate him then?”

“Hate him? Why…” She shook her head, flustered. “Sasha, why are you saying these things? It sounds like you’re accusing me of something.”

“I hear you’ve been helpful,” Sasha said flatly. “Helping the lords with their squabbles. Diplomacy was always your strong point.”

“I am the princess regent now,” Sofy retorted. “Such things are my responsibility.”

“Your responsibility to help the Larosa murder half-caste serrin and invade Saalshen?”

Sofy stared at her, disbelievingly. Anger followed. “And you’re here too! What does that make you, that you now ride against the armies of the Saalshen Bacosh?”

“A fool,” Sasha said bitterly. “A fool, but not a traitor.”

“And I am?”

“No, Sofy. Just a fool, like me. We’re all fools.”

They rode together in silence, amidst the great creak and sway of saddles and hooves. Peasants gathered on the hillside near their village, in huddled brown cloth, and stared fearfully at the passing army. Sofy swallowed her emotion.

“I don’t know what you want of me, Sasha,” Sofy said quietly. “I do the best I can for my people, as you do. My new family is not evil, they are just people, neither more perfect nor more flawed than most. I feel that perhaps I can do some good here. I’m good at diplomacy, as you say. Perhaps I can…perhaps I can moderate, or attempt to talk some reason to those who would not otherwise…”

“If they win,” Sasha said bleakly, “they’ll slaughter everyone. Serrin and half-castes they’ll torture first. Artists, craftsmen, philosophers, all these people are dangerous because they have dangerous ideas, they’ll be killed first. You can’t reason with it, Sofy, because reason is not at issue. Reason is never at issue. In that, Rhillian was right. Only blood will stop it, one way or the other.”

It was too much. Sofy felt her composure slipping, the tears resuming once more. “What would you have me do?”

“There’s nothing any of us can do. Serve the path of honour: family, nation, faith. When all’s said and done, it’s all any of us have.”

“And what about right and wrong?”

“A luxury I once believed in.” Sasha’s eyes were distant. “A fool’s dream. No more.”

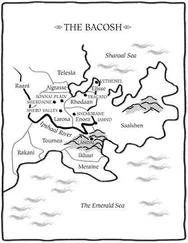

In the early afternoon, word spread down the column that the city of Nithele lay ahead, and there a council of war would be held between the Bacosh and Lenay armies. The Isfayen lords, Sasha, Sofy and Yasmyn all rode forward to arrive at the city in good time.

Nithele was a great walled city on the fork of land between two joining rivers. The Isfayen party halted along one riverbank, and now observed the high city walls. Many small boats sat on the bank, and cityfolk walked there, to gawp at the Army of Lenayin, or to throw nets, or to gather driftwood. Planks made a path on the bank to form a low wharf. Men, bare feet slipping, pants rolled to their knees, carried cargo from riverboats dragged bow-first onto the grass.

“How do men live in such places?” Great Lord Faras wondered darkly, observing the stark walls. The red cloth about his brow denoted him as a bloodwarrior, a sacred title in Isfayen, marked by many trials of manhood, and codes of conduct rigorous even by Lenay standards.

“The lowlanders like stone,” his daughter observed. “They live in stone cages, and fear the sky.”

“Do men live as this in the Saalshen Bacosh?” Faras asked Sasha.

“No,” she said. “Their cities are open. They have no internal enemies, and the Steel have not lost a battle in two hundred years, so they do not need these great walls.”

“Never trust a man with no enemies,” said Yasmyn, as they dismounted. Ahead, on the opposite side of the river from the looming Nithele walls, sat a small fishing village, with boats drawn up to the muddy riverbank. About it was a gathering of Lenay vanguard, with many banners and horses.

“The Saalshen Bacosh are surrounded by enemies,” Lord Faras countered his daughter. “Not only have they the mainland Bacosh, they had the Elissian Peninsula to their north, and made short work of them just now. The Steel have won so many glorious victories outnumbered and surrounded, I have no doubt we do not fight for the side of greater honour in this contest.”

The observation did not surprise Sasha. For the Isfayen, even more than in most of Lenayin, victory in battle brought honour, and honour was currency far richer than gold. When King Soros had liberated Lenayin from the Cherrovan a century before, the Isfayen had taken more convincing than most. Many Isfayen blood chiefs had challenged the new king to arms, and fought bloody battles against chieftains who converted to the new faith, be they Isfayen or from neighbouring Yethulyn or Neysh. Many Isfayen had never considered themselves to be Lenay at all, and had taken the liberation as an opportunity to fight for a separate kingdom…or indeed, for rulership of the greater Lenay kingdom. Thankfully, that prospect had so horrified the rest of Lenayin that they had banded together to ensure it never happened, and the resisting Isfayen chieftains had been crushed. That crushing had gained King Soros the respect of the rest, and Isfayen had submitted to rule from Baen-Tar, after the limited, uniquely Lenay fashion.

Yet the Isfayen had remained remote from the rest of Lenayin, their lands high, rugged and cold, their manners hostile, their justice crude. Even the Isfayen practice of the new faith was unique, a strange crossbreed of old traditions and new civilisation, their temples adorned with colours and flags, their holy stars inscribed with the spirit script of their ancient ways. And yet it was the faith, Kessligh had assured Sasha, that had brought the Isfayen into the Lenay fold to their current extent…which was not to say that they were brothers in the grand Lenay family, but merely that they did not kill the king’s taxmen on principle, or raid the neighbouring villages without at least a warning, or seek marriage with the daughter of prominent lords by galloping into town and throwing the girl over a saddlehorn. With the Isfayen, that was considered progress. Many in the priesthood had taken on the role of educators in wild Isfayen, and had thus attained an importance far beyond the worship of gods. Such men had brought the outside world to Isfayen, and given its inhabitants a reason to care about what lay beyond for the first time in their history.

The Great Lord Faras, Sasha well knew, was considered the best and brightest leader that Isfayen had ever had. Faras’s father had insisted he receive a Baen-Tar education, and now, the breeding showed. Faras had in turn insisted that his son Markan, and daughter Yasmyn, attend Baen-Tar, to learn the ways of the kulemran , or the “non-Isfayen.” That meant everyone from fellow Lenays to lowlanders to serrin. Now, Markan rode with the column, and was rumoured to have befriended Prince Damon, while Yasmyn had become the Princess Sofy’s closest confidante and protector. Many such ties were being forged on this ride, between leaders of lands with far longer history of mutual slaughter than friendship. Some of the credit for that lay with men like Lord Faras-a new kind of Lenay lord, educated and curious in a way that his predecessors had never been. And part of the credit, Sasha reluctantly conceded, lay with her big brother Koenyg. This had been his intention, to forge a nation on the road to war.

Читать дальше