Following the night’s banquet, Balthaar joined Sofy in their chambers, and dismissed the maids. He clasped her hands as they stood warm before the crackling fireplace, and Sofy’s heart beat faster.

“You are not certain of this war,” he said to her, softly. “Why then did you help today?”

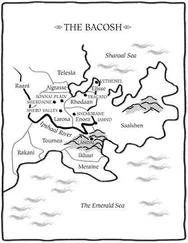

For a long moment, Sofy did not know what to say. “The Bacosh is a grand place,” she said at last. “I am the princess regent. I should try to do good while I have the opportunity. I see Lenays and Larosans sharing each other’s cultures, forging friendships. Surely it cannot be a bad thing.”

She said it firmly enough that she nearly believed it. Her instinct had always been to bring people together. She had never liked conflict. Peace between peoples was always good. She could make something good come of it, she was increasingly certain.

“I would like for many other things to be closer too,” said Balthaar. He kissed her. Sofy thought it rather nice, and let him. He took her to the bed, and began removing her clothes. They made love, and Sofy thought that rather nice too. He seemed rather taken with her, and was ever so gentle. Too gentle, almost, when her own passion took her. As Yasmyn had said, he was a handsome man, and if this were her heaviest royal burden, then it was not a hard one to bear.

Later, she lay in his arms, and gazed at the fireplace. Now she felt different, as though married life had truly begun. Yasmyn would be pleased, she thought, and found herself smiling. And she’d only thought of Jaryd three or four times.

Or maybe five.

Elesther Road was in chaos. The Steel made formations across some alley exits, and cavalry clattered along the cobbles, but the riot continued. Bodies lay unclaimed in the street. Others hung from windows, tied at the neck with rope. The Civid Sein had been this way, and the revenge was spreading.

Lieutenant Raine rode at Rhillian’s side, in full armour. Country folk watched them pass, roughly dressed and bearing all kind of rustic weapons. They roamed Elesther, near the Tol’rhen, and were working toward the Justiciary, while the Steel tried to keep armed mobs apart, with limited success.

“There’s too many of them,” Lieutenant Raine said darkly. “Hundreds more are pouring in every day. They make camp in the courtyards, and the homes of fled or murdered nobility. I need only a word, and I shall drive them back to the farms and villages from which they came.”

“I cannot,” Rhillian said. “Not until the Lady Renine and Alfriedo have been recaptured.” The last was most galling; she had not expected so daring an assault upon the Mahl’rhen itself. Five serrin were dead, a friend amongst them, and the young Lord Alfriedo missing. Still, from the broader perspective, she was not too concerned. “This violence is the work of the feudalists. They were warned of the country folk’s waning patience, and now they see the truth of it.”

“M’Lady,” said the lieutenant, “I am losing men to desertion. You know the Steel, you know the family that we are. The Steel never desert. Or rarely. But now I have noble-born enlisted and officers alike disappearing to see to their families, and I cannot in all honesty say that I blame them.”

Rhillian repressed a grimace and looked across the street. A door had been caved in, and several Steel were rounding up looters, beating them with little mercy. Tracato, most civil and orderly of all human cities, was falling apart.

“Council sits today,” she said. “What think the captains?”

“Council,” Lieutenant Raine snorted. “That word used to mean something. These men are not elected…”

“Neither were most of the old Council, in fairness.”

“But at least there was an appearance,” said Raine. “A pretence, no matter how they bought or bribed their way in. A Council without half its elected members, with all the nobility stripped away and replaced with Civid Sein cronies, is no Council at all worth the name.”

“Yet the Steel are sworn to obey the Council,” Rhillian said. “Will the captains do so? Captain Hauser does not give me a straight answer.”

Raine’s expression was bleak. His eyes lingered on a body, face down on the cobbles in a pool of dried blood. “I’m a country lad myself,” he said, “but I’d cut these Civid Sein scum down like vermin given the nod. This is not civilisation, M’Lady, this is rule of the mob, and I like it not. Nor do a majority of country folk, I believe, nor a majority of the Steel. I’ll not follow the orders of such people who now comprise the Council. But of course, I cannot speak for the captains.”

“If not the Council, then who?”

“M’Lady, I would follow you. I believe most of the dharmi feel the same. The feudalists are traitors, and the Civid Sein are a barbarian lynch mob. You walk the path between, and are not concerned with factions. I believe that is exactly what Rhodaan needs.”

“Lieutenant, you surprise me. Here I’d thought any expression of solidarity from a human would come with expressions of love and loyalty.”

“My father once told me that if you filled up all the goodness ever done by the promises of councilmen, philosophers, lords and priests in your left hand, while shitting in your right, the right hand will be full much faster. I’ll follow you precisely because you don’t ask me to love you.”

Rhillian looked at the young lieutenant for a long moment, then nodded. “I cannot in good conscience even ask you to trust me,” she added. “Most of what I do here, I do not like, and much ill will be done before I am through.”

“It was falling apart already, with what the feudalists were trying. There was little choice.”

“I cannot move against the Civid Sein just yet, Lieutenant, whatever horrors they should perform in the meantime. But soon, I promise.”

In the grand courtyard before the Tol’rhen, usually filled with factional and philosophical debate, there now camped a ragged army. There were many carts, mules and horses, amidst which country folk made makeshift camps. The smoke of cookfires filled the air, and an endless commotion of voices, animals, and from some quarters, shouted speeches.

Rhillian paused on the Elesther steps with Aisha to survey it all, and the Nasi-Keth who wandered through it, some talking and friendly with the new arrivals, others wary. She then pressed on through the main doors, guarded by Nasi-Keth, and into the dining hall. Here, familiar rowed benches had been rearranged crosswise, and crowded with people-perhaps half Nasi-Keth, and the other half not. At the far end, before the kitchens, a stage had been raised. Even above the roaring of the crowd, Rhillian could hear the booming voice of the speaker, in his black Tol’rhen robes. Only one man in the Tol’rhen possessed such a voice, and could rouse such a ruckus.

Rhillian made her way down the side of the hall, Lieutenant Raine at her back. “…and I say that we shall do unto them as they have done to us!” Ulenshaal Sevarien was roaring. “For so many centuries, the nobility have been a plague upon Rhodaan! They call it taxation, but in truth, it was theft! They are a gang of robber barons and thieves, and they have stolen wealth, and property, and the hard-earned labour of our sweaty and dirt-stained hands…”

“Our?” Rhillian wondered sourly. Sevarien’s hands were pink, plump and pale, like the rest of him. She doubted he’d ever pulled a plough, or raised a barn, or milked a cow in his life.

“We demand that the remaining feudal lands be redistributed amongst those who know and work it best!” A roar from the crowd. “We demand equality!” Another roar. “We demand the abolition of false titles and noble privilege!” Again. “We demand an end to the domination of Council by the wealthy few!”

Читать дальше