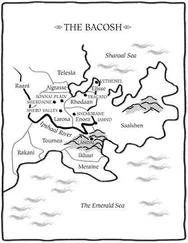

“Bold little buggers, aren’t they?” Zulmaher mused. “Well, keep at them. They’ve analysed our tactics quite well, they know we need to move fast, so there’s an awful lot of irregulars harrying our supply lines and terrorising any of the locals who might like to help. Without Saalshen and your talmaad , our progress would be significantly slowed. You have my thanks.”

“It’s what we’re best at.”

“It is at that,” Zulmaher conceded. “If only Saalshen had seen wisdom, and had put all of its evident martial talents to work over the last two centuries building some significant armies of its own, our current predicament might not seem so dire.”

Rhillian smiled. It was an old debate, and one that she had no intention of resuming here. It was a point, in fact, that the serrin had never stopped debating. Two hundred years ago, King Leyvaan had asked Saalshen a question, and today the greatest serrin thinkers were still undecided on the answer. No wonder so many of Saalshen’s human friends found serrin so exasperating.

“What happened here?” Rhillian asked, nodding to the castle and the preparations to march.

“Lord Crashuren came to terms,” said Zulmaher.

“Terms? When did we start offering terms?”

“When we started running out of time,” Zulmaher replied. “Crashuren is a small fish, and meanwhile the big fish escapes to the north. I do not have a day to waste bombarding yet another castle to wait for another pig-headed lord to come to his senses and surrender.”

“What are the terms?”

“He keeps his castle and lands,” said Zulmaher. “His minor lords will lower their banners and go home, his militia will do the same. In return, we won’t burn him down.”

Rhillian stared at him. Then at his surrounding captains. Several looked uncomfortable. One in particular appeared to be fuming, as though he could barely hold his tongue. Zulmaher, as ever, looked supremely unbothered.

“I just told a village of half-starved peasants, over the bodies of five villagers murdered by Lord Crashuren’s goons, that the lands they worked now belonged to them.”

“Best in future that you don’t,” said Zulmaher. “We don’t want to upset them with unfulfilled promises.”

“You intend to offer this deal to others?”

“It may prove necessary. If the Steel do not return to Rhodaan before the Lenays are ready to start fighting, Rhodaan will be lost. This military assault was always contingent on timeliness. If we are to defeat the Elissian Army on the field, we have no choice but to start skipping castles, and if that means we must make terms with their lordships, that is what we shall do.”

“We have received support from the peasantry,” Rhillian pressed. “Their talk to us of numbers and locations of enemy forces has been invaluable. Some have taken up arms to keep law and order in those lands where the old lords were deposed-”

“Closer to the border,” said Zulmaher, with a trace of impatience. Rhillian had the impression he was now speaking not just to her, but to his captains as well. Several of the captains were looking to her expectantly, as though wishing her to challenge further. Perhaps they’d not dared. Humans took rank so much more literally than serrin. “There were lots of friendly peasantry on the Rhodaani border, just as there were in the early days of Saalshen’s invasion into Rhodaan two hundred years ago. Those borders are porous, there is traffic back and forth in the dead of night, and those folks know us for the civilised people we truly are.

“Here, we are far from the border, and people are poor, uneducated and superstitious. They have much less support to offer us, and many won’t be too thrilled to see the only working system they’ve ever known abruptly pulled out from under them. Poor folk fear chaos as much or more than they fear their lords.”

“And how do you think to ensure that these lords will hold to the terms once the Steel have moved on?” asked Rhillian, sharply. “What will keep you safe from an attack on your rear, and on your lines of supply?”

“Noble honour,” said one of the captains, with heavy irony. Several smirked, finding that funny.

“No,” said Zulmaher, looking straight at Rhillian, “you will.” She stared back, a slight distance up for her-she was nearly as tall as the general, but her horse was not. There was a faint disconcertment in Zulmaher’s eyes, to meet her stare. “You say a thousand talmaad are on Crashuren lands…and perhaps three thousand in all Elisse?”

“Perhaps.”

“That is three thousand of the most formidable light cavalry ever fielded in battle. You can cover ground quickly between castles, remain alert of any uprisings, and carry word quickly should trouble arise. You can also harry, and gather quickly to put down any localised insurrection before it can gather pace.”

“We are not armoured cavalry to put down such heavy forces as the lords can muster,” Rhillian returned.

“When they muster in force, no,” Zulmaher agreed. “But these will be isolated pockets, if any. Their armour may be strong, but even light cavalry, in the numbers you possess, should be sufficient.”

Rhillian let out a snort, and stared at the castle. The flames on the tower showed no sign of abating. Large castles could withstand the hellfire for a greater time. Smaller castles like this one had little chance. Barely two days of bombardment, on the scale even a minor array of Steel artillery could deliver, would have towers ablaze and walls collapsing from the intense heat.

Serrin had given humans this power. Serrin oils, and serrin fires. Serrin steel, so formidable it had given the armies of the Saalshen Bacosh their name. Serrin bows had given human craftsmen ideas for new catapults, leading to advances in artillery that even without the hellfire were truly frightening. Human and serrin minds had combined to form a military of such killing power that it had no equal in all human lands. Thus far, the Steel had fought to protect Saalshen as much as human lands. But still, it was sometimes disquieting. Many great serrin thinkers, Rhillian knew, would look out at the Elissian battleground and wonder exactly what Saalshen had done to create this fire-breathing monster on its doorstep.

“Rhodaan had Saalshen’s approval for this war,” Rhillian said quietly, “on the understanding that the feudal nature of Elisse would be reversed. Feudalism is our death, General. It holds humanity in poverty, ignorance and powerlessness, leaving the masses of your people helpless to the predations of unchecked powerlust and fanatical religion-”

“It is not for Saalshen to tell humanity how to conduct our affairs with other humans,” General Zulmaher interrupted.

“No,” said Rhillian, “but it is for us to decide which of these actions we should support.”

Zulmaher’s grey eyes flashed dangerously. “Are you threatening to break your word to Rhodaan?”

“No more than you have broken your word to us.”

“I gave no such word.”

“You did. You said that you would liberate the Elissian people from their oppressors. We serrin have long memories, General. We know that a problem left unsolved will fester. This is our chance to solve the Elissian problem for good, and I feel you are squandering it.”

Zulmaher looked back to his army. The artillery lines were preparing to move.

“I am in no mood,” he said, “to have my commands dictated by the writ of Imperial Saalshen. You do what you will, M’Lady Rhillian. I shall do what I must, for Rhodaan.” He pressed his heels to his horse and rode toward the head of the forming column. His captains followed, several with final, unhappy looks at Rhillian. She stared at the castle, intact despite the burning tower, and wondered how many hundreds of Elissian fighting men were left within those walls, armed, armoured and undefeated. Perhaps five hundred, including heavy cavalry. And of Lord Crashuren, his lands intact, his rights undisturbed…all from here to the northernmost tip of the Elissian Peninsula, there would be other lords left the same, if General Zulmaher had his way.

Читать дальше