He took a deep breath, attempting to regain composure. No one interrupted him. “I can’t fight that, Y’Highness. No man can. We’ve safety in numbers, but a man can’t fight what he can’t see. If I hadn’t ordered our scouts back-”

“You did well,” Sasha interrupted. “We’ll need our scouts later.” Most of Lenayin’s scouts were Goeren-yai men, foresters with a great respect for the serrin. Serrin, being serrin, would know that. Surely it pained them to do it. But Saalshen was fighting for its right to exist, and serrin for their right to live.

Jurellyn gave Sasha a grateful look. “There’s something moving down the valley,” he continued. “None of us got close enough to hear. But one of us reckoned he could hear wheels, wooden axles. You could ask him more, but he got an arrow in the neck on the way back.”

“How long till dawn?” Koenyg asked no one in particular.

“Soon,” said a guardsman, lifting his palm to the horizon of stars. “Another hand.”

“Wait until the very first light,” said Koenyg. “We’ll just make a mess in the dark otherwise. Battle formations, and we’ll see what the dawn brings us. Father?”

King Torvaal merely nodded, and folded his arms within the black robe he wore. An assent, that he had faith in his eldest son’s command. Koenyg nodded, and strode off to give orders for the nobles to gather. Damon joined him, instructing a guardsman to wake Myklas. Sasha gave her father a final stare, and followed. Torvaal did not seem even to notice. He gazed at the horizon, with all the patience of stone, and awaited the rising sun.

Dawn brought them new silhouettes on the same ridgeline as the command post. The Steel had indeed crossed the valley in the night.

“ All of them?” Damon wondered aloud, as they stood atop the farmhouse roof, and viewed the enormous mass of glittering steel that now formed a huge line across the rolling fields to this side of the valley.

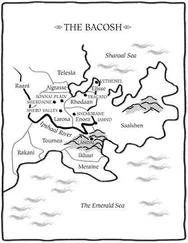

“Looks like,” Koenyg said. “They mean to flank us on our right, and push us back into the valley toward their own border.”

“With the forest at our back,” added the king, looking at the thick trees that covered the opposing slope. All had been surprised when Torvaal had clambered with his children from a horse’s back onto the rooftop. He looked to Sasha more animated than she’d ever seen him. “My son, they will advance on us, and attempt to win around our right flank. We must not let them.”

“Aye, Father. But the surest way to defend the right flank is to attack on the left. They have opened up their entire previous position, and we shall divide their attention by taking it.”

“Could be a trap,” Damon warned, looking out at the formerly surrounded castle.

“If they waste forces setting traps for our cavalry,” said Koenyg, “I would not mind a bit.” He looked down at the Great Lord Heryd, waiting patiently below in full black cloak and armour. “Lord Heryd! The left flank is yours! Should you win through, recall that the artillery is your primary target!”

“My Prince,” Heryd called up, “the north shall bring glory to Lenayin!” He turned and strode to his horses, armoured nobility close behind.

“Is that wise?” Damon asked his brother. “With the primary attack coming on our right flank, we commit our heaviest cavalry to the left.” All three northern provinces, refusing to divide their number to fight amongst pagans, had declared that they would form one entire flank together, leaving the remaining eight provinces to form the opposing cavalry flank, and the reserve. The arrangement was not as lopsided as it first sounded, given that the north were almost entirely cavalry, and were the heaviest in armour and weight of horse.

“I mean to break through, Brother,” Koenyg replied. “We must penetrate their defences and harry their artillery directly. We will achieve it by committing our heavy cavalry to their weakest defence.”

“Only look,” said Sasha, crouched low on the opposite slope of rooftop, “that weakest defence now means riding uphill from the valley.”

“These Enorans improvise well,” the king observed. “They appear as tactically astute as in all the tales. Do not underestimate them, my son.”

“I shan’t, Father. There is no clever move against this foe that could win us a painless victory. We shall fight them, and fight them hard. Damon, our time grows short, I need you on the right.”

“Aye,” said Damon, with something that sounded more like relief than trepidation. He and Koenyg embraced, and then he embraced their father. “Sasha,” he said then, “you’re with me.”

Koenyg embraced Sasha too. “Good call last night,” he told her. “Your details were wrong, but good call anyway.”

“I can’t be right all the time,” Sasha said lightly. She paused before her father. Torvaal extended his hand. Sasha took it hesitantly. Her father looked…concerned. There was a light in his dark eyes that she could not recall having seen before. It was not a confident light, but a light all the same. Sasha could not say if she found it encouraging or disturbing.

“Daughter,” Torvaal said gravely. “Lenayin called, and you came.”

That was it, Sasha realised. No mention of fatherly pride, no smile, nothing. Only this, reluctant acknowledgement. She was still the daughter who failed, the one who shamed all Lenay tradition in her choice of life, the one who had abandoned him as Kessligh had abandoned him after Krystoff’s death, and had finally led an armed rebellion against his personal authority.

“I’ve always come,” Sasha said coldly, and walked carefully across the roof to the edge, and a short jump to the ground. Damon followed, and she walked with him to their horses. “Why does he always do that?” she asked him plaintively.

“Do what?”

“Make me feel like my entire existence is an affront to him!”

“I heard a compliment,” Damon said drily. “That you rejected.”

“Where’s Myklas?” Sasha asked him, changing the subject.

“He rides with Heryd.”

Sasha did not like the thought of Myklas riding with the northern cavalry. But he was too young for a command, he was a good rider, and the northerners should have at least one royal riding with them.

Jaryd was waiting with the horses, and holding a round, wooden shield. He presented it to Sasha.

“What’s this?”

“And to think they ever called me a dunce,” Jaryd remarked.

“I can’t ride with this,” Sasha snorted. “I’m a girl, it’s too heavy for me.”

“It’s the lightest I could find, and it would barely trouble a fifteen-year-old lad,” Jaryd said impatiently, pressing it onto her.

“Take it or I’ll have you tied to a tree and left in the rear,” Damon told her, mounting quickly.

Sasha scowled, and tried its leather straps. It dragged on her arm, and did horrible things to her balance. She smacked it onto the horse’s saddle, and used that weight as a hold to drag herself up. She spurred off after Damon, Jaryd, several Royal Guards and three of Damon’s selected nobility. To their left, facing southward, the Army of Lenayin was slowly forming up.

“Sasha, I want you to ride with the Isfayen!” Damon shouted above the noise of their passage. “They have the hottest heads of the bunch, and they’re most likely to lose them in a fight! Try to keep them sane!”

“I’ll try,” said Sasha, “but I can’t promise anything!”

Upon the far right flank, the Lenay cavalry were forming. Damon, Jaryd and Sasha rode before the forward line, where vanguards for each Lenay province formed behind long banners that swirled in the gusting wind. A great, stamping, swirling mass of many thousands of horse, stretched across fields, fences and thickets of trees. They formed in provincial groups, nobility and standing company soldiers to the fore. They rode past the Valhanan cavalry, and Sasha glimpsed her old enemy, Great Lord Kumaryn, amidst a crowd of mounted noble riders, armour and leathers polished spotless for the occasion. A little across from the nobility, she spotted the banner of the Valhanan Black Wolves.

Читать дальше