Leigh Bardugo

SIEGE AND STORM

For my mother, who believed even when I didn’t.

THE BOY AND THE GIRLhad once dreamed of ships, long ago, before they’d ever seen the True Sea. They were the vessels of stories, magic ships with masts hewn from sweet cedar and sails spun by maidens from thread of pure gold. Their crews were white mice who sang songs and scrubbed the decks with their pink tails.

The Verrhader was not a magic ship. It was a Kerch trader, its hold bursting with millet and molasses. It stank of unwashed bodies and the raw onions the sailors claimed would prevent scurvy. Its crew spat and swore and gambled for rum rations. The bread the boy and the girl were given spilled weevils, and their cabin was a cramped closet they were forced to share with two other passengers and a barrel of salt cod.

They didn’t mind. They grew used to the clang of bells sounding the hour, the cry of the gulls, the unintelligible gabble of Kerch. The ship was their kingdom, and the sea a vast moat that kept their enemies at bay.

The boy took to life aboard ship as easily as he took to everything else. He learned to tie knots and mend sails, and as his wounds healed, he worked the lines beside the crew. He abandoned his shoes and climbed barefoot and fearless in the rigging. The sailors marveled at the way he spotted dolphins, schools of rays, bright striped tigerfish, the way he sensed the place a whale would breach the moment before its broad, pebbled back broke the waves. They claimed they’d be rich if they just had a bit of his luck.

The girl made them nervous.

Three days out to sea, the captain asked her to remain belowdecks as much as possible. He blamed it on the crew’s superstition, claimed that they thought women aboard ship would bring ill winds. This was true, but the sailors might have welcomed a laughing, happy girl, a girl who told jokes or tried her hand at the tin whistle.

This girl stood quiet and unmoving by the rail, clutching her scarf around her neck, frozen like a figurehead carved from white wood. This girl screamed in her sleep and woke the men dozing in the foretop.

So the girl spent her days haunting the dark belly of the ship. She counted barrels of molasses, studied the captain’s charts. At night, she slipped into the shelter of the boy’s arms as they stood together on deck, picking out constellations from the vast spill of stars: the Hunter, the Scholar, the Three Foolish Sons, the bright spokes of the Spinning Wheel, the Southern Palace with its six crooked spires.

She kept him there as long as she could, telling stories, asking questions. Because she knew when she slept, she would dream. Sometimes she dreamed of broken skiffs with black sails and decks slick with blood, of people crying out in the darkness. But worse were the dreams of a pale prince who pressed his lips to her neck, who placed his hands on the collar that circled her throat and called forth her power in a blaze of bright sunlight.

When she dreamed of him, she woke shaking, the echo of her power still vibrating through her, the feeling of the light still warm on her skin.

The boy held her tighter, murmured soft words to lull her to sleep.

“It’s only a nightmare,” he whispered. “The dreams will stop.”

He didn’t understand. The dreams were the only place it was safe to use her power now, and she longed for them.

* * *

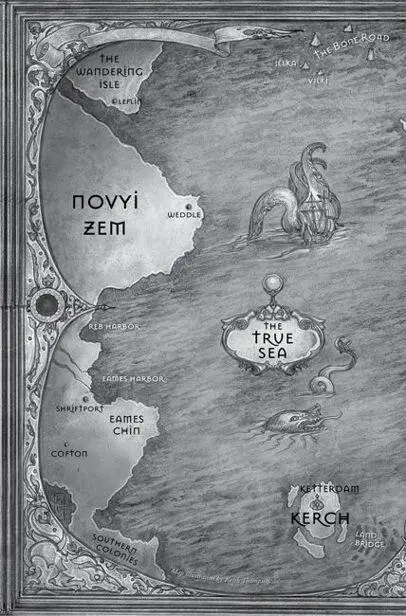

ON THE DAYthe Verrhader made land, the boy and girl stood at the rail together, watching as the coast of Novyi Zem drew closer.

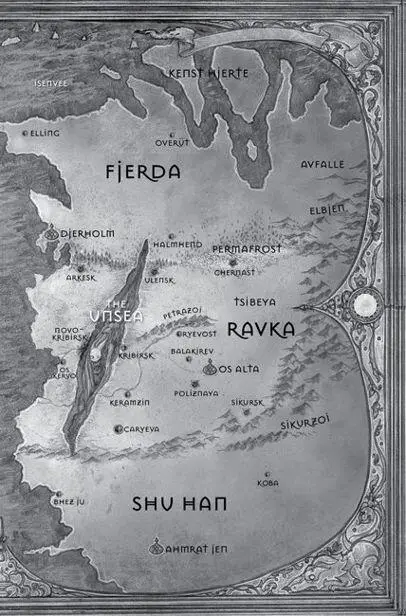

They drifted into harbor through an orchard of weathered masts and bound sails. There were sleek sloops and little junks from the rocky coasts of the Shu Han, armed warships and pleasure schooners, fat merchantmen and Fjerdan whalers. A bloated prison galley bound for the southern colonies flew the red-tipped banner that warned there were murderers aboard. As they floated by, the girl could have sworn she heard the clink of chains.

The Verrhader found its berth. The gangway was lowered. The dockworkers and crew shouted their greetings, tied off ropes, prepared the cargo.

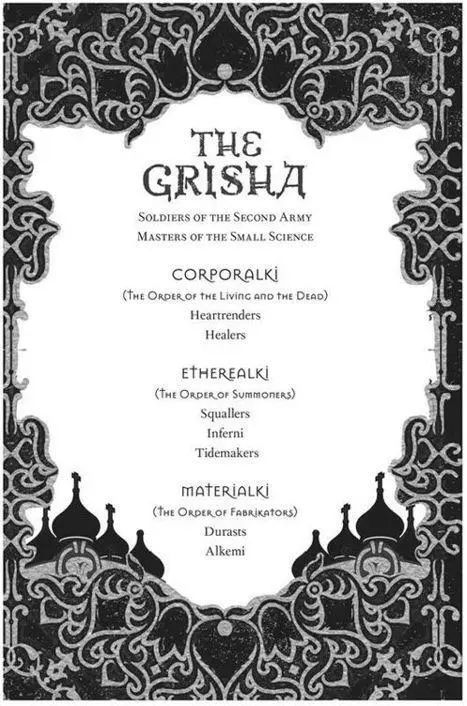

The boy and the girl scanned the docks, searching the crowd for a flash of Heartrender crimson or Summoner blue, for the glint of sunlight off Ravkan guns.

It was time. The boy slid his hand into hers. His palm was rough and calloused from the days he’d spent working the lines. When their feet hit the planks of the quay, the ground seemed to buck and roll beneath them.

The sailors laughed. “ Vaarwel, fentomen! ” they cried.

The boy and girl walked forward, and took their first rolling steps in the new world.

Please , the girl prayed silently to any Saints who might be listening, let us be safe here. Let us be home.

TWO WEEKS WE’Dbeen in Cofton, and I was still getting lost. The town lay inland, west of the Novyi Zem coast, miles from the harbor where we’d landed. Soon we would go farther, deep into the wilds of the Zemeni frontier. Maybe then we’d begin to feel safe.

I checked the little map I’d drawn for myself and retraced my steps. Mal and I met every day after work to walk back to the boardinghouse together, but today I’d gotten completely turned around when I’d detoured to buy our dinner. The calf and collard pies were stuffed into my satchel and giving off a very peculiar smell. The shopkeeper had claimed they were a Zemeni delicacy, but I had my doubts. It didn’t much matter. Everything tasted like ashes to me lately.

Mal and I had come to Cofton to find work that would finance our trip west. It was the center of the jurda trade, surrounded by fields of the little orange flowers that people chewed by the bushel. The stimulant was considered a luxury in Ravka, but some of the sailors aboard the Verrhader had used it to stay awake on long watches. Zemeni men liked to tuck the dried blooms between lip and gum, and even the women carried them in embroidered pouches that dangled from their wrists. Each store window I passed advertised different brands: Brightleaf, Shade, Dhoka, the Burly. I saw a beautifully dressed girl in petticoats lean over and spit a stream of rust-colored juice right into one of the brass spittoons that sat outside every shop door. I stifled a gag. That was one Zemeni custom I didn’t think I could get used to.

With a sigh of relief, I turned onto the city’s main thoroughfare. At least now I knew where I was. Cofton still didn’t feel quite real to me. There was something raw and unfinished about it. Most of the streets were unpaved, and I always felt like the flat-roofed buildings with their flimsy wooden walls might tip over at any minute. And yet they all had glass windows. The women dressed in velvet and lace. The shop displays overflowed with sweets and baubles and all manner of finery instead of rifles, knives, and tin cookpots. Here, even the beggars wore shoes. This was what a country looked like when it wasn’t under siege.

Читать дальше