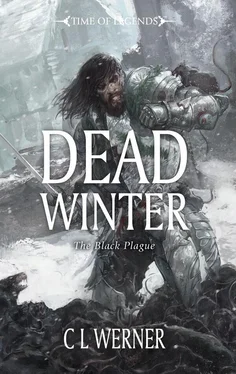

C. Werner - Dead Winter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «C. Werner - Dead Winter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Games Workshop, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dead Winter

- Автор:

- Издательство:Games Workshop

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781849701518

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dead Winter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dead Winter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dead Winter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dead Winter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The prospect of a hungry winter, however, was compounded in the last weeks of Brauzeit. It was then that the diktat of Emperor Boris against the Dienstleute bore its ugly fruit. Discharged from the service of their noble lords, unable to find work to sustain themselves, the dispossessed peasants had mobilised under the leadership of a grizzled old firebrand named Wilhelm Engel. A veteran of many campaigns, a soldier who had served as adjutant to generals and warlords, Engel organised his people with military precision and discipline. In those last weeks of Brauzeit, he led five thousand starving soldiers into the streets of Altdorf to seek redress from the Emperor in whose name they had fought.

From across the Empire, from every province, the Dienstleute continued to come. Every morning, a delegation from Engel would appear before the marble gates of the Imperial Palace with a petition, a request to treat with the Emperor and plead their cause before him. Engel’s demands were straightforward: bread to feed his men, work to sustain them.

Weeks later, Engel’s delegates were still seeking their audience with the Emperor. The ‘Bread Marchers’, as the discharged Dienstleute had come to be called, took to the fields and meadows of Altdorf, constructing shantytowns from wattle and thatch. The largest of these took shape in the wide expanse of the Altgarten, overwhelming the tranquillity of the park with a labyrinth of squalor and poverty. Altdorfers contemptuously named the place ‘Breadburg’, and cursed both it and the scruffy squatters who infested it.

The presence of so many rootless and desperate men was a cause of concern to the inhabitants of Altdorf. The little family farms which helped sustain the city were the constant target of poachers and thieves. Herdsmen took to keeping their livestock inside their homes; granaries began to resemble armed camps with companies of guards patrolling around them night and day. For days, the people of Altdorf shuddered at accounts of the von Werra stables — the stablemaster’s entire stock being rustled in the dead of night. Cook-fires shining from the squalor of Breadburg told the rest of the story.

From the towers of the Reikschloss the extent of the shantytown could be viewed in full. Patrolling the battlements of their fortress, the knights of the Reiksknecht watched as the numbers of Engel’s Bread Marchers continued to swell. As more and more of the park was razed to make room for the expanding morass of shacks and hovels, the knights felt a coldness settle about their hearts. From their vantage, they could see the terrible menace that was growing right inside the city walls.

Baron Dettleb von Schomberg felt the tension in the air as he took his morning constitutional. Three circuits of the castle walls had been his habit since taking the position as Grand Master of the Reiksknecht. He felt that the combination of exercise and fresh air was conducive to good health and a clear mind. This morning, however, he was making his fifth circuit of the wall and still his thoughts were filled with dread.

Von Schomberg’s heart went out to the Bread Marchers and their cause. He felt a great sympathy for these men who had lost the security of their homes and positions. At the same time, he could not afford to ignore the threat these desperate, starving men represented to the peace and security of Altdorf.

Lost in his thoughts, von Schomberg didn’t see Captain Erich von Kranzbeuhler until he almost walked straight into the young knight.

‘My apologies, my lord,’ Erich said, snapping to attention.

Von Schomberg gave the knight a tired smile. ‘Entirely my fault,’ he said, then uttered a dry chuckle. ‘I should thank you. If not for your intervention I might have walked right off the parapet.’

‘Scarcely the heroic death worthy of the Grand Master,’ Erich replied, falling into step beside von Schomberg as the baron marched towards the edge of the parapet. The baron gazed out across the slanted roofs of Altdorf, concentrating his eyes upon the jumbled confusion of Breadburg.

‘There are many things beneath the dignity of the Reiksknecht,’ von Schomberg sighed. ‘But I fear we will be called upon to do them just the same.’

‘The Bread Marchers?’ Erich asked, following his captain’s gaze. ‘Surely that is a problem for Schuetzenverein?’

Von Schomberg shook his head, his expression turning even more grim. ‘Perhaps at one time the city guard could have handled Engel’s people, but the problem has grown too big for the Schueters.’ He slammed his palm against the cold stone of the parapet. ‘By Verena! Why didn’t Prince Sigdan take steps to stop this! Thousands of starving men swarming into his city and he does nothing!’

‘Perhaps he didn’t have the heart to turn them away,’ Erich suggested. ‘These aren’t a rabble of vagabonds; these are Dienstleute discharged by their lords without thought or provision. Men who risked their lives trying to keep the Empire safe.’

‘I share his sentiment,’ von Schomberg said. ‘Except for the officers, every knight in the Reiksknecht is a dienstmann, a vassal of Emperor Boris. I am not unfamiliar with the travails of belonging to such station, but a leader cannot allow sentimentality to cloud his judgment. Engel’s people should have been turned away.’

‘Maybe the decision wasn’t Prince Sigdan’s to make,’ Erich suggested. ‘Increasingly, the Emperor has come to view Altdorf as his own personal suzerainty. If it was his will to have the Bread Marchers repulsed, he would have ordered them removed by now.’

Von Schomberg lifted his eyes, staring out past the Altgarten, past the Great Cathedral of Sigmar to where the Imperial Palace sat upon its hill surrounded by its megalithic dwarf-built walls. The golden pennants of Boris Hohenbach fluttered from the spires of the palace, proclaiming to all and sundry that the Emperor was in residence. Safe behind the high walls of his palace, surrounded by his cronies and sycophants, it was just possible that the Emperor really was oblivious to the unrest gathering right on his doorstep.

The baron’s face contorted into a grimace of pain. There was another possibility, one that von Schomberg found much easier to believe. The Emperor was exploiting the crisis, allowing it to escalate. He thought back to the meeting of the Imperial Council and the outrage expressed by the dignitaries over the new taxes being imposed across the Empire. Special dispensation had been granted to Drakwald and Westerland, in recognition of the unrest in those lands. Conspicuously, the Emperor hadn’t extended such dispensation upon Altdorf and the Imperial Army. The Dienstleute who composed most of the troops would be taxed just like any other peasant, the monies levied to be applied to the Imperial Treasury.

For all his abuse of power, Emperor Boris was still answerable to the electors who had given him that power. He had made it his practice to play one province against another, ensuring that every elector had an enemy he hated more than his Emperor. He further ensured that his word and his power were the only thing preventing these smouldering hatreds from blazing up into outright warfare.

Now, however, it seemed he was playing a different game. Emperor Boris was using the distress of certain provinces to create a state of dependency between them and himself. Only by the largesse of Boris Goldgather would Westerland be empowered to reclaim Marienburg, only by his consideration would Drakwald recover from the depredations of the beastkin. Another emperor, a new emperor, might not be so sympathetic to their plight and impose upon them the same obligations as the other provinces.

It was a bitter kind of loyalty Boris would gain, but it was the only sort he would trust — a loyalty built upon need and dependence rather than respect and admiration.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dead Winter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dead Winter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dead Winter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.