She marched away from Tolcet and the girl, shoving through the refugees.

“Where are we going?” Onion said.

“To make the wizards come down,” Halsa said. “I’m sick and tired of doing all their work for them. Their cooking and fetching. I’m going to knock down that stupid door. I’m going to drag them down their stupid stairs. I’m going to make them help that girl.”

There were a lot of stairs this time. Of course the accursed wizards of Perfil would know what she was up to. This was their favorite kind of wizardly joke, making her climb and climb and climb. They’d wait until she and Onion got to the top and then they’d turn them into lizards. Well, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad, being a small poisonous lizard. She could slip under the door and bite one of the damned wizards of Perfil. She went up and up and up, half-running and half-stumbling, until it seemed she and Onion must have climbed right up into the sky. When the stairs abruptly ended, she was still running. She crashed into the door so hard that she saw stars.

“Halsa?” Onion said. He bent over her. He looked so worried that she almost laughed.

“I’m fine,” she said. “Just wizards playing tricks.” She hammered on the door, then kicked it for good measure. “Open up!”

“What are you doing?” Onion said.

“It never does any good,” Halsa said. “I should have brought an axe.”

“Let me try,” Onion said.

Halsa shrugged. Stupid boy, she thought, and Onion could hear her perfectly. “Go ahead,” she said.

Onion put his hand on the door and pushed. It swung open. He looked up at Halsa and flinched. “Sorry,” he said.

Halsa went in.

There was a desk in the room, and a single candle, which was burning. There was a bed, neatly made, and a mirror on the wall over the desk. There was no wizard of Perfil, not even hiding under the bed. Halsa checked, just in case.

She went to the empty window and looked out. There was the meadow and the makeshift camp, below them, and the marsh. The canals, shining like silver. There was the sun, coming up, the way it always did. It was strange to see all the windows of the other towers from up here, so far above, all empty. White birds were floating over the marsh. She wondered if they were wizards; she wished she had a bow and arrows.

“Where is the wizard?” Onion said. He poked the bed. Maybe the wizard had turned himself into a bed. Or the desk. Maybe the wizard was a desk.

“There are no wizards,” Halsa said.

“But I can feel them!” Onion sniffed, then sniffed harder. He could practically smell the wizard, as if the wizard of Perfil had turned himself into a mist or a vapor that Onion was inhaling. He sneezed violently.

Someone was coming up the stairs. He and Halsa waited to see if it was a wizard of Perfil. But it was only Tolcet. He looked tired and cross, as if he’d had to climb many, many stairs.

“Where are the wizards of Perfil?” Halsa said.

Tolcet held up a finger. “A minute to catch my breath,” he said.

Halsa stamped her foot. Onion sat down on the bed. He apologized to it silently, just in case it was the wizard. Or maybe the candle was the wizard. He wondered what happened if you tried to blow a wizard out. Halsa was so angry he thought she might explode.

Tolcet sat down on the bed beside Onion. “A long time ago,” he said, “the father of the present king visited the wizards of Perfil. He’d had certain dreams about his son, who was only a baby. He was afraid of these dreams. The wizards told him that he was right to be afraid. His son would go mad. There would be war and famine and more war and his son would be to blame. The old king went into a rage. He sent his men to throw the wizards of Perfil down from their towers. They did.”

“Wait,” Onion said. “Wait. What happened to the wizards? Did they turn into white birds and fly away?”

“No,” Tolcet said. “The king’s men slit their throats and threw them out of the towers. I was away. When I came back, the towers had been ransacked. The wizards were dead.”

“No!” Halsa said. “Why are you lying? I know the wizards are here. They’re hiding somehow. They’re cowards.”

“I can feel them too,” Onion said.

“Come and see,” Tolcet said. He went to the window. When they looked down, they saw Essa and the other servants of the wizards of Perfil moving among the refugees. The two old women who never spoke were sorting through bundles of clothes and blankets. The thin man was staking down someone’s cow. Children were chasing chickens as Burd held open the gate of a makeshift pen. One of the younger girls, Perla, was singing a lullaby to some mother’s baby. Her voice, rough and sweet at the same time, rose straight up to the window of the tower, where Halsa and Onion and Tolcet stood looking down. It was a song they all knew. It was a song that said all would be well.

“Don’t you understand?” Tolcet, the wizard of Perfil, said to Halsa and Onion. “There are the wizards of Perfil. They are young, most of them. They haven’t come into their full powers yet. But all may yet be well.”

“Essa is a wizard of Perfil?” Halsa said. Essa, a shovel in her hand, looked up at the tower, as if she’d heard Halsa. She smiled and shrugged, as if to say Perhaps I am, perhaps not, but isn’t it a good joke? Didn’t you ever wonder?

Tolcet turned Halsa and Onion around so that they faced the mirror that hung on the wall. He rested his strong, speckled hands on their shoulders for a minute, as if to give them courage. Then he pointed to the mirror, to the reflected Halsa and Onion who stood there staring back at themselves, astonished. Tolcet began to laugh. Despite everything, he laughed so hard that tears came from his eyes. He snorted. Onion and Halsa began to laugh, too. They couldn’t help it. The wizard’s room was full of magic, and so were the marshes and Tolcet and the mirror where the children and Tolcet stood reflected, and the children were full of magic, too.

Tolcet pointed again at the mirror, and his reflection pointed its finger straight back at Halsa and Onion. Tolcet said, “Here they are in front of you! Ha! Do you know them? Here are the wizards of Perfil!”

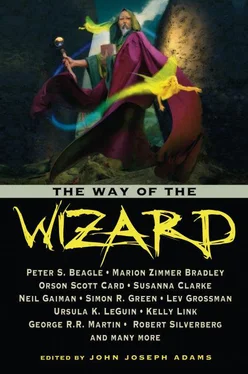

Neil Gaiman’s most recent novel, the international bestseller The Graveyard Book , won the prestigious Newbery Medal, given to great works of children’s literature. Other novels include American Gods, Coraline, Neverwhere , and Anansi Boys , among many others. In addition to his novel-writing, Gaiman is also the writer of the popular Sandman comic book series, and his books Coraline and Stardust were recently made into feature films. Gaiman’s short fiction has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, including my own The Living Dead, By Blood We Live, and The Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes . Most of his short work has been collected in the volumes Smoke and Mirrors, Fragile Things, and M is for Magic . His latest book is a hardcover edition of his poem, Instructions , illustrated by Charles Vess.

Most Americans have probably heard someone say, “If you believe that, I’ve got a bridge to sell you,” referring to New York’s Brooklyn Bridge. It’s just taken for granted that handing over your money to a con man who offers to “sell” you such a famous landmark would be the ultimate example of gullibility. Believe it or not though, this old cliche is based on a real scam that was perpetrated over and over again on naive immigrants whose heads were filled with exaggerated notions of America as a land of opportunity. Con artists would memorize the routes of the beat cops and then set up signs saying “Bridge for sale” when they knew the police would be out of sight. Police repeatedly had to evict people who had been swindled and were attempting to charge tolls for crossing “their” bridge. As newcomers to the city gradually become more sophisticated, the con died away, but lived on in movies such as Every Day’s a Holiday and even in a Bugs Bunny cartoon (“Bowery Bugs”).

Читать дальше