The little girl sat alone on the edge of the mandrake field, the red-stained stone folded in her fist, finally certain that the little man was gone. She closed her eyes, and tears soaked her eyelashes until they traced courses like rivers, like questing roots, down the soft slopes of her cheeks.

Rachel let the tears dry on her face before she opened her eyes again. When she pried her salt-crusted lids apart, she was surprised to see a hare browsing between the mandrake tops. It looked nervous at her presence, but it merely munched with one eye on her, momentarily content.

She watched it for a few minutes, its awkward hops more endearing than any other rabbit she had ever seen. And somehow, she knew what to do, just as if someone whispered the instructions in her ear.

“Come,” she called. She focused her mind on rabbit thoughts, soft and welcoming as fresh-turned soil. Inside her, she could feel a strange flickering, as warm and welcome as a candle flame. She focused her mind and felt the flickering steady and grow even warmer.

The rabbit hopped right to her.

Rachel laughed as she stroked its soft, humped back. Its fur beneath her fingertips felt luxuriant and warm, softer than anything she’d ever touched. She scooped the little creature up and rested her cheek on its side.

Around her, the flowers of the mandrakes nodded on their stalks like tiny sleepy eyes. Beneath the soil, a new root began to reach toward the sun — nameless but not alone.

Kelly Linkis a short fiction specialist whose stories have been collected in three volumes: Stranger Things Happen, Magic for Beginners, and Pretty Monsters . Her stories have appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Realms of Fantasy, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Conjunctions , and in anthologies such as The Dark, The Faery Reel, and Best American Short Stories . With her husband, Gavin J. Grant, Link runs Small Beer Press and edits the ’zine Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet . Her fiction has earned her an NEA Literature Fellowship and won a variety of awards, including the Hugo, Nebula, World Fantasy, Stoker, Tiptree, and Locus awards.

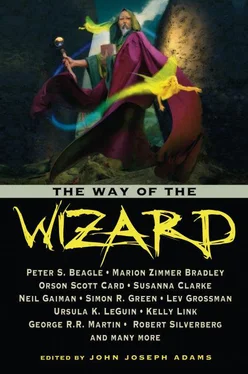

A common issue that comes up when discussing wizard stories is this: Why don’t wizards rule the world? After all, wizards supposedly wield immense magical powers, and yet most fantasy kingdoms still seem to be governed by kings and dukes and lords, whereas the wizards are relegated to being merely advisors, or else they’re off skulking in some humble tower or hovel or cave. Why don’t any of these so-called wizards aim a little higher? Where’s their ambition? Couldn’t they just march into town, toss around a few fireballs, and declare themselves boss?

Of course, many of them are probably happier contemplating arcane mysteries, but surely some must take an interest in local affairs? Can’t they use their powers for good? In Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn , Molly Grue admonishes Schmendrick the Magician, “Then what is magic for? What is the use of wizardry, if it cannot even save a unicorn?” Answer: “That’s what heroes are for.”

But why? Our next story, which originally appeared in the young adult anthology Firebirds Rising , is built around this basic conundrum: Why don’t those darn wizards ever get off their butts and actually do something for a change?

The Wizards of Perfil

Kelly Link

The woman who sold leech grass baskets and pickled beets in the Perfil market took pity on Onion’s aunt. “On your own, my love?”

Onion’s aunt nodded. She was still holding out the earrings which she’d hoped someone would buy. There was a train leaving in the morning for Qual, but the tickets were dear. Her daughter Halsa, Onion’s cousin, was sulking. She’d wanted the earrings for herself. The twins held hands and stared about the market.

Onion thought the beets were more beautiful than the earrings, which had belonged to his mother. The beets were rich and velvety and mysterious as pickled stars in shining jars. Onion had had nothing to eat all day. His stomach was empty, and his head was full of the thoughts of the people in the market: Halsa thinking of the earrings, the market woman’s disinterested kindness, his aunt’s dull worry. There was a man at another stall whose wife was sick. She was coughing up blood. A girl went by. She was thinking about a man who had gone to the war. The man wouldn’t come back. Onion went back to thinking about the beets.

“Just you to look after all these children,” the market woman said. “These are bad times. Where’s your lot from?”

“Come from Labbit, and Larch before that,” Onion’s aunt said. “We’re trying to get to Qual. My husband had family there. I have these earrings and these candlesticks.”

The woman shook her head. “No one will buy these,” she said. “Not for any good price. The market is full of refugees selling off their bits and pieces.”

Onion’s aunt said, “Then what should I do?” She didn’t seem to expect an answer, but the woman said, “There’s a man who comes to the market today, who buys children for the wizards of Perfil. He pays good money and they say that the children are treated well.”

All wizards are strange, but the wizards of Perfil are strangest of all. They build tall towers in the marshes of Perfil, and there they live like anchorites in lonely little rooms at the top of their towers. They rarely come down at all, and no one is sure what their magic is good for. There are wobbly lights like balls of sickly green fire that dash around the marshes at night, hunting for who knows what, and sometimes a tower tumbles down and then the prickly reeds and marsh lilies that look like ghostly white hands grow up over the tumbled stones and the marsh mud sucks the rubble down.

Everyone knows that there are wizard bones under the marsh mud and that the fish and the birds that live in the marsh are strange creatures. They have got magic in them. Boys dare each other to go into the marsh and catch fish. Sometimes when a brave boy catches a fish in the murky, muddy marsh pools, the fish will call the boy by name and beg to be released. And if you don’t let that fish go, it will tell you, gasping for air, when and how you will die. And if you cook the fish and eat it, you will dream wizard dreams. But if you let your fish go, it will tell you a secret.

This is what the people of Perfil say about the wizards of Perfil.

Everyone knows that the wizards of Perfil talk to demons and hate sunlight and have long twitching noses like rats. They never bathe.

Everyone knows that the wizards of Perfil are hundreds and hundreds of years old. They sit and dangle their fishing lines out of the windows of their towers and they use magic to bait their hooks. They eat their fish raw and they throw the fish bones out of the window the same way that they empty their chamber pots. The wizards of Perfil have filthy habits and no manners at all.

Everyone knows that the wizards of Perfil eat children when they grow tired of fish.

This is what Halsa told her brothers and Onion while Onion’s aunt bargained in the Perfil markets with the wizard’s secretary.

The wizard’s secretary was a man named Tolcet and he wore a sword in his belt. He was a black man with white-pink spatters on his face and across the backs of his hands. Onion had never seen a man who was two colors.

Tolcet gave Onion and his cousins pieces of candy. He said to Onion’s aunt, “Can any of them sing?”

Onion’s aunt indicated that the children should sing. The twins, Mik and Bonti, had strong, clear soprano voices and when Halsa sang, everyone in the market fell silent and listened. Halsa’s voice was like honey and sunlight and sweet water.

Читать дальше