“And you want to leave.”

“Yes. With you.”

“Wow. This is… sudden.”

“Not for a Tufa. I know your song. It hurm… horm…”

“Harmonizes?”

She nodded emphatically. “Har-mo-nize-es with mine. Sorry, the big words are hard right now.”

He bit his lip. “Curnen, I don’t want to say. I owe you a lot, but… you’re not human. ” Even though he knew it was true, he felt weird verbalizing it. She certainly looked human, and small, and sad. If he touched her, she’d be warm and alive. But in a blink, she could transform into something ethereal, otherworldly, alien.

Curnen nodded. “I know. But I can be her, too.”

And again, for an instant, Anna stood there before him.

“No!” he yelled, and turned away. “Don’t ever do that!”

“I’m sorry,” she said quickly. “I won’t do it again, I promise. Some people, some men… like that.”

“Not me.” When he looked, she was herself again. “I’m sorry, I know you want to leave, and I don’t blame you. But I don’t think I could handle it.”

She nodded as if she expected his answer. “That’s how all the songs end. But we each lost half our hearts. If we put our halves together…”

He said nothing.

Sadly, she turned and walked away. Her bare, rough-soled feet skitched against the blacktop.

“Curnen, wait.”

She stopped halfway up the shoulder of the road. Her posture had already regained some of its primal slouch.

“You really can leave? I mean, it didn’t go so well for Rockhouse. Or Bronwyn Hyatt.”

She nodded. With a little smile, she said, “I am not chained to this spot. And the winds know I’ll be back.”

“And are you sure you want to? I mean, I live in a city, in a real flat part of the country. We don’t have hills. We don’t even have many trees. We have a lot of cars, and corn, and people, and noise.”

She chewed her lip thoughtfully. “Do you have songs?”

He half smiled. “Yeah. Songs we got.”

She climbed back down to the road. “Then I’m sure.” She touched his face with her rough fingers. “But hear me, Rob Quillen. The pain of your loss will return. Less, but still considerable. I know you’ve worked hard to release it, but it can still take hold of you. I will help you sing away the fury, Rob, but I will not bear it for you.”

“Okay,” he said, although he didn’t know exactly what she meant.

She grabbed his wrist in a grip like a hydraulic press. “You have to understand me. There are no half measures here. I am your girl. I will be your woman. But I will never be your victim. If you ever try to turn me into that, I will sing your dying dirge.”

Her eyes were, for a moment, as cold as any reptile’s. Rob recalled the brief glimpse of Curnen, blood-spattered and wild, with a chunk of human flesh in her teeth. Then it vanished and she was small, and fragile, and his. He felt it as surely as he did gravity.

And it felt good. Whatever the source, whether it was his own emotion or something impinged on him by her, it felt good. He felt whole.

“I’ll be careful,” he said sincerely.

“And I’ll be patient.” Then she kissed him.

He gently took her arm and guided her to the car. As he did, he glanced at the Cloud County sign and stopped. Something had changed about it. It still read, Welcome to Cloud County, Tennessee, and the painted mockingbirds still flew in the corners. But there was a difference.

“Hey, didn’t that sign used to say something else?” He was certain there’d been more, an epigram or motto of some sort. Of course there had; he’d nearly crashed trying to read it.

Curnen shrugged. “I don’t know. Until now, I could only see the back of it.”

“Huh,” Rob said. Then he helped her into the passenger seat and buckled the belt around her.

Then Rob Quillen and his fairy lover drove away into the west.

Twenty years later…

Denton Sizemore had no time to react. One moment the road was empty; then suddenly she was there, right in front of him. He hit a deer last year, just after he’d gotten his license, and knew how sickening that felt. This was far worse; the sound his truck made when it struck the woman would stay with him forever.

He dialed 911 on his cell phone as he jumped out of the truck. No one used this old highway anymore, and there were no houses within five miles. The only building was the abandoned remains of an old roadhouse nightclub, its parking lot overgrown with kudzu, two faded wood cutouts of what looked like dice or dominoes still mounted on its roof. This was the last place he’d expect to find a pedestrian, especially one who dashed into the road right in front of him.

He knelt beside her. From the way her eyes stared at the overcast sky, he knew she was dead, and he almost threw up. The emergency dispatcher asked him calmly to describe the victim.

“Sh-she looks about thirty,” he told the dispatcher. “She’s got red hair, and she’s wearing clothes like they did twenty years ago. No, I don’t see a purse anywhere.”

Following the dispatcher’s instructions, he tentatively touched her neck for a pulse. Her head lolled to one side the way it could only if her neck was broken. He nearly screamed.

“Y’all, please hurry!” Sizemore said, tears filling his eyes. “I don’t want to be alone here with a corpse !”

The dispatcher stayed on the phone with him until the police and ambulance arrived. The paramedics quickly loaded the body onto a stretcher and carried it away, while the state trooper sympathetically took his statement.

One of the paramedics, a woman with long black hair, put a hand on Sizemore’s shoulder. He recognized her as one of the Needsville Tufas, although he didn’t know her name.

“Don’t feel too bad about it,” she said gently. “It was an accident, that’s all.” She leaned closer. “And really, this woman died twenty years ago.”

Sizemore didn’t understand the strange comment, but the EMT’s smile and touch eased his panic. She hummed a tune he almost recognized as she climbed into the ambulance and closed the door. Red lights flashing, it drove away into the mist.

All song lyrics are original, with the exception of two stanzas from “Hares on the Mountain,” a traditional English ballad first printed in One Hundred English Folksongs : For Medium Voice, a landmark 1916 songbook edited by Cecil J. Sharp (1859–1924); one stanza of “Pretty Saro,” another traditional English ballad, first published in Alan Lomax’s North Carolina Booklet in 1911; and “Little Omie Wise,” which first appeared in The Greensboro Patriot (North Carolina) newspaper on April 29, 1874.

And of course, “Wrought Iron Fences” by Kate Campbell, from her 1997 album Moonpie Dreams, and used by her generous permission. She gets honorary Tufa status for that.

The painting The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke by Richard Dadd is currently on display in the Tate Gallery in London. Its presence in the United States is entirely fictional.

Blood Groove

The Girls with Games of Blood

The Sword-Edged Blonde

Burn Me Deadly

Dark Jenny

Wake of the Bloody Angel

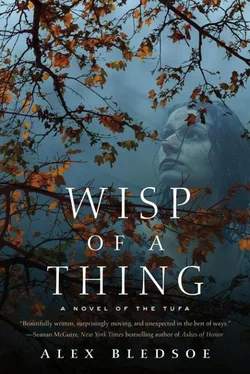

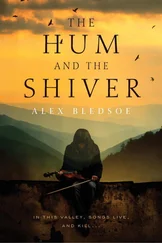

The Hum and the Shiver

Alex Bledsoe grew up in West Tennessee, but now lives in Wisconsin. Besides his tales of the Tufa, he also writes the Eddie LaCrosse and Memphis Vampires series. His official website can be found at www.alexbledsoe.com.

Читать дальше