Dagmira, for her own part, quite rightly demanded to know what I was doing. “Snooping,” I said. “Will you help me?”

She knew me well enough by then to take my bluntness and audacity in stride. We collected the fallen candle and matches and went downstairs, where we discovered that despite the late hour—I judged it to be midnight, or nearly so—someone else was also awake. We heard noises from the vicinity of the kitchen, and stole quietly in the other direction, toward the cellar door from which Rossi had emerged that morning.

It proved to be locked. I lit the candle and examined the latch, unwilling to be thwarted so easily. From what I could see, the lock was of a simple sort; the key acted to pivot a narrow bar on the other side. The gap was just large enough to admit the cover of my faithful notebook. With nary a tinge of remorse, I tore the cover off, and with its length was able to reach through and lift the bar, allowing the door to swing open.

Stairs led downward, into a veritable sink of Rossi’s distinctive and unpleasant odor. Dagmira followed me with the candle, its light bobbing and dancing with each step. And then, when we reached the bottom, the flame reflected off a hundred glassy surfaces.

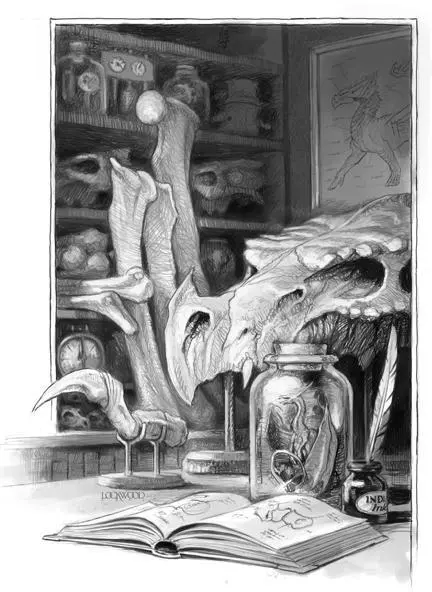

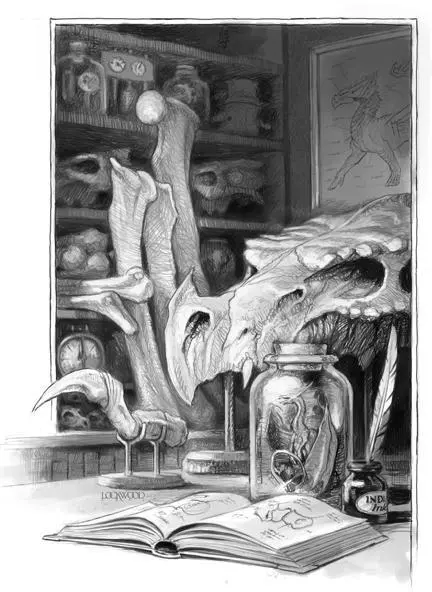

The cellar was no taxidermist’s workshop. It was a chemical laboratory, the likes of which I had never before seen, and have only seen since on the premises of a university. I lacked the proper names for most of the things I saw: bottles and beakers and retorts, rubber tubing and large, shallow tubs. Poor judge of such things though I was, the entire array must have cost a fortune, in transport costs alone.

Dagmira touched the candle flames to a pair of lamps, brightening the room so I could see further. The light played over a well-used notebook on the table, crates of chemicals underneath. I knew their labels would be familiar before I even looked: Chiavoran make, most of the names unknown to me, but the sulfuric acid immediately recognizable. So Astimir had indeed gotten it from here. But why ?

The answer, or at least part of it, lay at the far end of the room.

There was no question of mistaking the bones for ursine or lupine. I had drawn their like in the open air, hurrying for fear that they would disintegrate before I could record all the details. I had seen mineral-encrusted samples preserved by some trick of chemistry in the great cavern near Drustanev. Here they lay in an enormous pile: uncounted numbers, far too many to come from a single beast, not with that stack of femurs against the wall.

Dragon bones. Processed in this laboratory so that they would not break down—my breath stopped at the thought. With what Rossi had developed, we could study them with vastly greater accuracy; we could answer mysteries of anatomy and osteology that had puzzled dragon naturalists since the founding of the field.

But he did not want them for study; of that, I was sure. Had he intended to sell them to collectors, he would have kept each individual’s skeleton separate, and he would have preserved all the bones. I saw none of the smaller, more irregular components, and only one skull, placed atop a table in the manner of a trophy. The rest were roughly sorted, and they were long bones all: femurs and humeri and great, curving ribs.

ROSSI’S LABORATORY

My hand trembled as I reached out and picked up a rib. Even in those days, with my limited experience of animal physiology, I marked the extraordinary lightness of the thing. It was necessary; the weight of ordinary bone would never have allowed something so large as a dragon to fly. And where the bones of birds were delicate, these were tremendously robust for their thickness, or they would have collapsed under the burden of muscles and organs. Acting on sudden suspicion, I gripped the rib and tried to snap it across my knee. It did not give.

Dragon bones, perfectly preserved, as if they were still within the body of their dragon.

How many had Rossi and Khirzoff killed, to achieve this success?

Behind me, I heard Dagmira gasp. It broke me from my stunned contemplation of the bones. I turned and found her standing, candle holder almost slipping from her nerveless fingers, staring into the palm of her other hand, where something small gleamed.

I went quickly to her side. “What is it?”

Wordlessly, she extended her hand to me. The object was a ring: a small, cheaply made signet. The emblem, when I examined it, bore words abbreviated in a manner I recognized as Chiavoran. In a voice made tight with fury, Dagmira said, “That is Jindrik’s ring.”

Gritelkin. “You are sure?”

“That is the school he went to, in Chiavora, after he ran away from Drustanev.”

It did look like a university ring. And when I turned it over in my fingers, I found letters engraved on the underside of the face: J.G. Not Rossi’s own ring, then. It was proof enough.

We had to leave the lodge as soon as possible. All of us.

But when I slipped the ring over my thumb and turned with Dagmira to go, we found a new light descending the stairs. A moment later, it emerged into the cellar, and it was borne in Gaetano Rossi’s hand.

His surprise, I think, was for finding two women in his laboratory. Our lights would have long since given away that someone was prying about in his things. I wondered, briefly, whom he had expected. Jacob? Lord Hilford?

In his other hand he carried a plate of sausage, cheese, and bread. A midnight snack, I supposed, to fortify him in his work. He laid it down atop his notebook, not taking his eyes off us, and then said, “Well. What do I do with you two?”

He spoke Chiavoran, of course, which Dagmira would not understand. I imagined she could make out his tone well enough, though: speculative and threatening. Licking my lips, I answered in his own tongue, hoping to flatter our way out of this cellar. “Your work is remarkable. Men have tried to preserve dragon bone before, but so far as I know, you’re the first to succeed. It’s a tremendous discovery for science.”

Rossi dismissed that last word with a sneer. “Science is for withered-up old men in dusty rooms. We have better plans for those bones. Stronger than wood, and lighter than steel; what could we not do with that?”

It was not at all what I had expected him to say. “You—you are talking about industry ?”

“I’m talking about wealth,” he said. “And power. The nations of the world already squabble over iron; that will only grow worse with time. The man who can offer them an alternative will be able to name his price.”

Despite the circumstances—which should have held my attention very firmly indeed—I could not stop my mind from leaping to consider Rossi’s point. Stronger than wood and lighter than steel, yes; as braces or struts, dragonbone would be worth—well, far more than its weight in gold. But you could not build an engine out of it, not by riveting ribs or ilia together. Unless he had some notion of how to—

That was as far as my thoughts got before Rossi put down his light, and picked up a knife.

“But never mind what I’m doing with the bones,” he said. “The real question is what to do with a pair of spies.”

I had thought myself frightened when that rock-wyrm attacked us on our way to Drustanev, or when I believed us stalked by an ancient demon. It was nothing, I discovered, to facing a man who might be about to murder me in cold blood.

Threats from natural sources I can handle calmly; threats from humans bring out the most foolish impulses in me. The next words from my mouth were very ill considered indeed, from the standpoint of wanting to survive, but I could not stop them. “You killed Gritelkin. Why? Because he learned about this?” I gestured toward the dragon bones.

Читать дальше