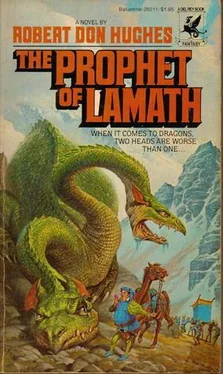

The dragon—suddenly, incredibly under attack immediately put all interpersonal animosity aside, and dealt with the problem. Vicia and Heinox focused their combined fury on the tightly jammed mass of screaming humanity that fouled their ancient nesting place and unleashed anew that dreaded power that had altered the landscape of the entire world so many hundreds of years before. When the sound of the blast died away, eight thousand Chaons were missing, and the pass was clear of everything save ashes.

So began the second great period of burning. Vicia-Heinox was angry. The two heads could never again ignore their duality—they were no longer one, and there was no changing the fact. But that day they realized that, though they hated one another, they hated people even more. Mankind needed a new education in the power of the dragon, and they vowed to be harsh teachers.

Many of Venad’s archers were also burned away by the dragon’s blast. Those who survived dropped their weapons and ran from the hillsides, but few survived to reach the plain, for the dragon now leapt high into the air and belatedly scorched the mountainsides of Dragonsgate free of forests.

Pahd was no longer laughing. He and Dorlyth were just reaching the plain when the first flash jolted them, They looked at each other in shock, for that flash could only mean one thing. The Maris had no use for history, true, but they knew all of the ancient tales—especially tales of the dragon. Now all the stories had been proved true by the brilliance of that terrible blast. Without another clash of swords, the great host that had been locked in mortal combat throughout the day suddenly dispersed in every direction save east. Chaon and Mart rode side by side, shouting encouragement to each other as they fled the field of battle.

“By the powers,” said Tohn in dismay. “Somehow they woke the beast!” Tohn gripped the battlements of his castle and stared. He had been surveying the wreckage done to his beautiful green fields, by the battle when the flash from the pass caused him to look up. He watched as the dragon rose screaming from behind the rocks; he shuddered at the sight of those bizarre heads as they scorched away trees and shrubs. The dragon’s double-throated scream was audible all the way across the valley and it shocked Tohn into action. He raced down the outer staircase as fast as his old legs would carry him, calling what names of his children, cousins, nephews, and aunts he could remember, calling out other names that he couldn’t put with faces, in the hope that someone would answer.

“Get inside! Get inside!” he called. From the battlements ran others who had witnessed the catastrophe, and these echoed his warnings to scramble for cover. Tohn tried to run across the courtyard, but his breath was gone, and he paused to regain it, coughing amid the flying dust. Then he remembered. “That merchant lad,” he said aloud, to no one but himself, and he grabbed a lungful of dirty air and dashed back to the main gate of the keep.

“Grandfather! What are you doing?” a young matron screeched, but he either did not hear her, or chose to pay her no mind. He slipped the heavy bolt and threw his weight behind the door to push it open.

There was only time for a quick glance around, for escaping Maris and Chaons alike saw that crack in the castle gate and turned to ride frantically toward it. Tohn leapt back inside and heaved the gate shut behind him. He slipped the bolt back in place even as the frightened soldiers jumped from their horses and ran to bang on the door’s heavy planks. The young merchant had been nowhere in sight.

“I cannot,” Tohn sighed, more to himself than to the shouting warriors beyond the barrier. “For my family’s sake, I cannot.” Powerful arms gripped him on either side, and he was carried across the courtyard by teenage youths whose names he could not remember.

“His mind is a little addled by the battle, I think,” said the young mother who preceded them toward the inner keep.

“The dragon is loose. Grandfather!” she yelled in his ear. “We need to get inside or he might harm us!” Tohn said nothing as these, his offspring, patronized him. Let them think him a senile fool, he told himself. Perhaps they’d put him to bed. Tohn’s heart was breaking at the tragedy beyond his walls. Though he could not get enough air into his lungs, his chest seemed to be trying to explode. He needed sleep. Oh! Tohn thought, how I need sleep!

WHEN ASHER RETURNED to the capital, he encamped his forces on a field west of the city. It was here that he received Pelmen and his party.

“I hope the dungeon was not too uncomfortable,” he said, greeting Pelmen. “I felt you would be safest there until my return. Who are these with you?” Pelmen introduced Bronwynn and Rosha, then introduced Erri. The little sailor had met them that morning at the dungeon gate, holding Minaliss’ reins in one hand, and the white pony’s reins in the other.

“You’ve become a loyal follower very quickly,” Asher observed as he acknowledged the short seaman’s bow.

“Once you’ve discovered the truth, it’s senseless not to be loyal to it.” Erri shrugged, and Asher gazed back at Pelmen.

“My feelings exactly. I apologize. Prophet, for nearly having you killed on such a false charge. Is the arm the only ill effect you suffered?” Pelmen’s dislocated shoulder had been reset and bandaged, and his left arm hung now in a sling.

“Only my arm, Asher. And please, don’t hold yourself responsible. You were acting sincerely.”

“Yes,” Asher said grimly. “Sincerely wrong. The monster—” Asher paused. “How quickly we change.

I’ve never called the dragon that before.” He shook his head, then went on. “The dragon is a-burning.” Pelmen frowned. “I was afraid of that. I saw several charred sections as we made our way through the city.”

“And not the city alone. The beast has ruined crops, destroyed villages, and consumed large quantities of our population. Truly, this is no god.” Asher spat the words out in disgust. “I’ve spoken with—him and discovered it for myself. The dragon is divided.”

“I’m thankful you discovered it when you did, Asher.” Pelmen smiled, rubbing his arm. Then his smile faded.

“So. The dragon is a-burning. And he can’t do that unless both heads cooperate. It appears that Vicia-Heinox has reunited himself in order to punish the rest of the world.”

“What can we do? Is there any way to restrain the monster?”

“One way,” Pelmen said. “By killing him. And the method of doing that has yet to be discovered.” Asher frowned. “As a boy, I was taught that the dragon is uncreated and immortal. But you say he can be killed—and you’ve proved yourself a Prophet. If he must be killed—who could discover such a way but you?” Asher’s gaze was earnest.

Pelmen sighed. He was thinking of Serphimera’s vision. “Who but me?” he said softly. Then he looked around at Bronwynn. “You have the book?”

“Right here.”

“I’ll study it, Asher. I’ll look. This book told us of the beast’s creation—perhaps it will yield some clue to its destruction as well. But it may take time—”

“Take what time you need, Prophet. You realize already the urgency of the situation.” The situation was urgent indeed… and not just for Lamath.

Vicia-Heinox appeared everywhere. Peasants in regions far removed from Dragonsgate, peasants who disbelieved the dragon tales because they had never met a man who had seen the beast, now saw and feared. For Vicia-Heinox did not visit an area without giving it a sampling of dragon-burn.

It was not true that the dragon was systematic in his devastation—but had the beast reasoned out some pattern, it could not have been more crippling to the mental state of mankind. He struck arbitrarily, burning one man’s field while leaving the field next to it to ripen. Witnesses babbled incoherent accounts to their disbelieving neighbors, then hours later those neighbors would chatter their own tales of horror. Villages collapsed into smouldering cinders as the inhabitants watched and wept. Elsewhere, entire populations disappeared, leaving silent, lifeless dwellings as a mute testimony to the dragon’s voracious appetite. Vicia-Heinox distributed his misery generously. His path of destruction could be traced through all three lands. While he was certainly not just or fair in his punishment, at least he vented his anger impartially. If there was a soul in any of the lands who did not know the dragon was a-burning, it was because he had cut himself off from the rest of the race and had hidden under the ground. The cry was everywhere the same.

Читать дальше