The warder listened silently to her protests, then shrugged. “Priestess, I can only do as I am ordered. I cannot explain the reasons why some sentences are commuted and others carried out. It is the will of the dragon.”

“It is not the will of Lord Dragon!” Serphimera stamped, and the warder looked away, embarrassed. “I thought that the King understood the need for this man’s execution! It was my understanding that Asher had ordered this death, and that the King had agreed! Why would the King overrule his Chieftain’s order!”

“The King did not overrule Asher.”

“Then who?”

Serphimera snarled.

“It was Asher himself who stopped the drawing of this Prophet. He seems to believe the Prophet is right.” Serphimera stood rigid, her body frozen as her mind wrestled to make some sense of this new information. “Asher?” she said at length. “The Prophet has convinced even Asher?” The warder nodded curtly and turned away, hoping the woman would take the hint and leave. He hated to get involved in religious politics. Give him the dirt and blood of true crime any day. At least then, the killing made some sense.

Serphimera gave him his wish. She went out the door of the dungeon with her mind aswhirl. She gazed downward, and the cobblestones seemed a million miles away. She kept walking, putting one foot before the other, fearing that if she stopped she would plunge to her death on those distant rocks below. She walked no more in Lamath, but in a world of dreams too suddenly shattered. Serphimera felt hopelessly lost amid a universe of yelling people. It was only her reputation and her characteristic dress that saved her from the riot begun by the rampaging tugolith. Fighting crowds would clear out of the way for the dazed Priestess to pass, then would fall back to fighting. Her supporters finally found her, and guided her through the flood of angry citizens to the safety of the secluded garden.

“Pelmen, are you awake?”

“Yes…” He really wasn’t, but he was getting there. Pelmen’s eyes opened, and he gazed up into Bronwynn’s face.

She beamed back at him, and shouted, “Rosha! He’s awake!” Rosha came and knelt down in the straw by Pelmen’s side as Pelmen struggled to sit up. The Prophet yelped in pain as his weight shifted onto his left arm, and he would have fallen back had Bronwynn not supported his head.

“Why don’t you just lie there a while?” the girl asked sensibly, and he smiled.

“Where am I?”

“In the dungeon.”

“They didn’t kill me?”

“You really need me to answer that?”

“No,” he murmured. He thought for a moment. “Do you know why they didn’t?”

“We’ve no idea,” Bronwynn answered.

“B-but the warder was m-m-most gentle with you when he carried you in. He s-said something about Asher wanting you whole.” Then Pelmen remembered. He nodded, and forced himself to sit up without using his left arm. Then he moved across the floor to lean against the damp wall.

“Does that make any sense?” Bronwynn asked.

“I think so, yes. Somehow Asher discovered that I was only telling the truth about the dragon. That means he has probably been into Dragonsgate.”

“Then Asher is marching on Chaomonous?” Bronwynn worried aloud, a bit surprised at herself for even caring.

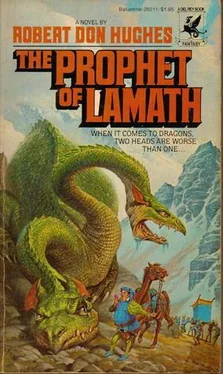

“He’s probably been in Dragonsgate. Through Dragonsgate, and into Chaomonous? I doubt it. Vicia-Heinox has never before allowed an army to pass Dragonsgate—never in his history. Why should he do so now?”

“B-but if he has?”

Rosha wondered.

Pelmen raised an eyebrow. “If he has, I would truly like to know what’s happening now. For if any army has passed Dragonsgate, into any other land, then the world has just witnessed the gravest battle since the time before the dragon—the grandest clash since the parting of the One Land.”

“It is clear now,” Serphimera murmured much later, after the sun had left the sky and the garden’s torches had been lit. “I see my responsibility clearly.”

“And what is it, my Priestess?” begged one disciple. “What can we do, now that this charlatan is again free to roam the streets?”

“Too long I’ve wandered these delightful fields of Lamath, sending others to make the ultimate devotion in my place.”

“No, Priestess—” one began, and another follower wept aloud in anticipation of her words.

“It is time for the Priestess herself to journey to Dragonsgate.”

“No, Priestess, you cannot! Asher’s warriors line every section of road from here to the Lord Dragon’s nest! You’ll not be allowed to pass. Please, stay and reconsider!” _ “It’s time, I tell you!” All the protestors saw the fire in her eyes. They sat quietly then, watching. When she spoke again, Serphimera was once more in control of herself.

“He has slipped away today. But I have seen this Prophet’s doom! A time will come when this one clad in sky blue will be pulled into that sky by the mouths of Lord Dragon, and the Lord will tear him in two!” She glanced around at the circle of faces, her jaw set, her expression carved of stone. “Perhaps,” she said, “my own sacrifice can somehow hasten that day.”

“Yet there is still the hazard of the journey! How will you come to Dragonsgate, if Asher’s warriors hold the road?” Serphimera’s eyelids flickered, and her gaze burned the speaker’s cheeks pink. “Am I not able to plan my own passing?” she asked.

“Forgive me, Priestess,” he mumbled.

“There is a man of hideous countenance who proved a fearsome enforcer in the cleansing of the Prophet’s own monastery. Find me that man!”

“Yes, Priestess,” someone replied.

In moments runners were in the streets, searching for word about an ugly man whose name no one knew, but whose face no one could forget.

Serphimera climbed the stairs to the balcony, and gazed to the south. Humbly she saluted the dragon with crossed arms, and curtseyed. “I come. Lord Dragon,” she murmured quietly, then slipped back into the, lighted interior of the mansion.

“THERE THEY ARE!” Doriyth said ominously, and he pointed with his sword. Through the pass below rode warriors armed from head to toe in plates and mail of gold. The afternoon sun reflected brightly off that highly polished metal, wrought by the finest artisans in the world—the craftsmen of Chaomonous. The line continued to come, clearly visible to Doriyth and his companions, who watched unobserved from the mountaintop above. “You see them, Pahd? Pahd?

Pahd, are you sleeping again?”

“Hunh?” Pahd awakened with a start. He sniffed, and glanced around him. “Where are we?”

“We’re preparing to: go into battle!”

“Oh, yes.” Pahd smiled drowsily. “I was just getting a little rest before the excitement starts. Not easy to do on horseback.” He leaned over his mount’s neck to watch the column a moment, and his eyes brightened. “Ohh. Lots of them, aren’t there?”

“Aren’t you glad you chose to get up this morning?” Doriyth mocked. “You might have missed it.”

“Come now, Doriyth. You aren’t still angry at me for not arriving in time to break Tohn’s siege. Had we arrived sooner, I may well have killed the old gray merchant. Then he never would have had the chance to warn us of all this.”

“True enough, Pahd. But as I recall, you were more angry than I.”

“And understandably so!” Pahd complained. “To get out of bed and ride all that way just to watch two Lords make peace is not my idea of an exciting outing. You might at least have staged a duel of champions.” The west mouth of Dragonsgate opened onto a large 309 plain. Far below them, on a slight rise in that expanse of green meadow, stood the castle of Tohn mod Neelis. Its gates were tightly shut, and Tohn and his people had gathered within to wait out the battle that would decide the future of the Mar. They had been waiting this way for weeks, for Tohn had expected Talith’s army long before this. His young cousins chafed under his restrictions and mocked him behind his back. But Tohn would not change his mind. He had informed Dorlyth that he would open his gates for no one, either to enter or to exit. His keep would remain an island of calm in the midst of a stormy ocean of battling armies.

Читать дальше