“He isn’t sending Lamathian citizens away to be eaten, is he?” Asher asked, his back still turned to her.

“General Asher,” Serphimera began, and a chill chattered through him. Her voice had taken on that seductive quality that had so mesmerized him in the past. “I know you are a believer. I can see it in your life, hear it in the way you issue orders. The dragon will reward you for that.” He did not turn to look at her, so she came to stand directly behind him and continued to soothe in subtle tones as she worked to make her point. “You have expanded the realm of Lamath farther north than any war chieftain before you—surely you don’t imagine you did that on your own? I know you don’t.

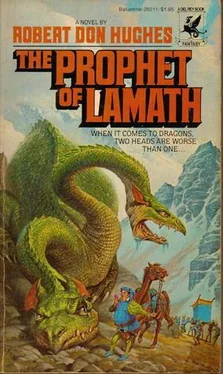

And I know, too, that were you to hear this counterfeit Prophet, you would be as anxious as I to remove him from Lamathian life.” She placed her hands on his shoulders, an electric touch that made his back tingle. “General Asher, he has no tradition. He does not abide by the old understanding, but brings a new belief. And—he says the dragon is divided.”

“What does he say?” The General turned to face her, and was nearly overpowered by her warmth and closeness.

“That the dragon is at war with himself!” General Asher scowled. “At war with himself?” Serphimera danced lightly away, her point made. “Simple heresy,” she added, but she needn’t have. The angry red glow in the General’s cheeks gave evidence that he was already convinced. “He needs to be captured,” Serphimera advised, “and locked away, so that he can do no more harm to others. Or to himself,” she added quietly. “I know where you may find him—”

“Oh, I know where he is,” Asher growled, cursing his own impulsiveness. “He travels with our own navy!”

“What for?”

Serphimera demanded.

“It is the tradition that a Prophet in Lamath at wartime rides with the ships to battle.”

“You could not have waited until after I met him?” she snarled bitterly.

“No. Time was too critical. I needed to rush our navy onto the sea before the Chaon fleet reached the delta and bottled us in the river.”

“Can he be stopped?”

“Not now. Your meeting took place two days ago?”

“I came as swiftly as I could—”

“You are too late. His boat passed by here yesterday, and the fleet left the harbor of Lamath this morning. By this time it should be moving into the ocean—if not already engaged in battle.” Serphimera clenched her jaws in frustration. Asher patted her on the shoulder, then immediately withdrew his hand, surprised at his own familiarity with this, the greatest Priestess of the land. “Calm yourself. If the Chaons sink his vessel, we need concern ourselves with him no longer. If he does return, I myself will meet him at the dock, and carry him from the victory celebration to the dungeon.”

“Never had much dealings with prophets, myself,” the wiry sailor remarked. “Always got a queer feeling when I passed one of them dragon statues.”

“Does the same thing to me,” Pelmen said merrily, and he drew a deep draught of salty air into his lungs. It had been some time since he last saw the ocean, and even longer since he had traveled on it. He noticed the sailor was eyeing him with curiosity, and smiled. The wind and the salt had somehow renewed his spirits.

“I take that as strange, I do,” Erri the sailor observed. “Seems like a prophet fellow would get a real thrill out of one of them monsters.”

“Not this Prophet.” Erri scratched his beard. “You seem a strange Prophet, at that.”

“Oh, I hope so.”

Pelmen grinned.

“Aren’t you afraid the Lord Dragon’11 be displeased?”

“The dragon isn’t the Lord.” Erri jumped as if he’d stepped barefoot onto a jellyfish, and looked around for a place to hide. “Listen, Prophet, a ship is no place to play blasphemy!

Suppose the Lord Dragon decides to burn you with a little flick of lightning! What’s to prevent me from being charred along with you?”

“Relax, Erri. I know that dragon, and he can’t hear me. We’re turning into the wind again,” Pelmen added, and Erri jumped up to help trim the yards as the oars along either side of the vessel slipped out in unison and began thrashing the water like so many centipede legs. The sounds of a beating drum and groaning men rose through the boards of the deck, dampening Pelmen’s cheerful mood. There had been a time when he, too, had worked an oar in the bowels of a battleship. He preferred to forget the experience.

Those who rowed below were mostly Chaon slaves. Ironic, Pelmen thought, that the Chaon fleet would be powered primarily by Lamathian muscle. He doubted there were many Maris below deck. Maris made poor oarsmen. They were too small, usually, to pull much weight, and they spent too much time being seasick. Setting a Mari to an oar was like trying to hitch a mountain goat to a plow. When sea traders went shopping for oarsmen, they usually chose slaves from the other seafaring nation. Of this Pelmen was sure, however: when the fleets closed for battle, Lamathian slaves would be cheering their Chaon masters, while Chaon slaves would show new loyalty for Lamath. Nationality had little meaning in the stinking hold of a battleship. What mattered there was survival.

Erri returned, swinging himself down to sit on a pile of rope. “So tell me, then,” he continued, picking up the conversation as if he’d never left, “why are you a Prophet of the Dragon if you have such a low opinion of the beast himself?”

“I’m not a Prophet of the dragon,” Pelmen replied evenly. Erri stared, his eyes and mouth very wide. Then he glanced up at the sky, fully expecting a cloud to appear suddenly in the clear blue and aim a fire bolt directly at them.

Nothing happened, and he looked back at Pelmen.

“Nothing happened,” he observed needlessly.

“Of course not.”

“I don’t understand. If you’re not a Prophet, why pretend to be a Prophet?”

“I didn’t say I wasn’t a Prophet. I just said I wasn’t a Prophet of the dragon.” Erri nodded, but his expression said he was puzzled. “I didn’t know there was any other kind.”

“Didn’t it ever seem strange to you, all this noise and excitement about a dragon?”

Erri shrugged. “Not really. Religion is always strange. It doesn’t have to make sense.”

“It does to me,” Pelmen murmured quietly. “Yeah, but you’re a Prophet, see. Religion is supposed to make sense to a Prophet.” Pelmen didn’t say anything. “Isn’t it?”

“Has nothing to do with religion, Erri. Has nothing to do with the dragon, either. What’s important is the Power, Erri, not the Dragonfaith. All the rest is just wrapping.” Erri chuckled. “See, you are a Prophet after all. I Can’t understand anything you say.”

“Is that because you’re afraid you shouldn’t? Or because you do understand, and are afraid of what it might mean?” Pelmen’s eyes had been scanning the southern horizon as they spoke, and now he saw golden triangles, far away—the sails of the Chaon fleet. “Better warn the Seachief, Erri. We’re about to meet our brothers from the south.” At that moment bells began ringing on all the ships, and the salty air was filled with shouted orders. Erri scampered off to his station, but a thought sprang into his mind and he swiftly climbed back to ask Pelmen, “Just one thing. If you don’t believe in the Dragon, how you going to help us in this battle?”

“The Power will have to show you that, my friend. At this point I really have no idea.” The oars pulsed more quickly, in rhythm with the increasing pace of the oarsmaster’s gavel. It was good the oarsmen could not see what they were rowing into. The sea warriors who stood in the prow of the battleship watched with dismay as more and more golden sails appeared on the horizon.

Читать дальше