“You mustn’t scold him, my Lady,” he puffed, “for I can attest that he kept his promise to the letter.” Plari stopped to gasp for a breath.

“Seventeen opponents?”

“They weren’t any good. Mother. If you’re going to make me practice, would you at least find me some decent competition?”

“Such as?” his mother challenged.

“I don’t know. Muldi mod Sag, of the northwest…”

“Killed by a cavern bear,” Plari put in. “Up in the mines.”

“What was he doing there?” Pahd asked.

“You sent him,” the seneschal replied simply.

“Oh yes, now I remember,” Pahd said uncertainly, trying to remember. “But isn’t Muldi a bear’s-bane?”

“He was.” Plari shrugged. “Apparently, bears don’t put as much stock in such titles as we men do.”

“Go on,” Chogi urged, tapping her foot impatiently.

“Name me another.”

“Ah, Doriyth mod Karis, or—”

“Ah-hah!” Chogi gloated, and Pahd looked at her, puzzled. “Doriyth mod Karis is locked in siege with Tohn mod Neelis, or have you forgotten?”

“Of course I haven’t forgotten,” Pahd protested, having forgotten. “Why did he lay siege to Tohn mod Neelis?”

“He didn’t! Tohn attacked him! He sent you word almost two weeks ago. Don’t you remember anything?”

“I remember how to sword-fight,” Pahd sniffed, offended.

“Tell her, Plari.”

“Oh yes, my Lady, he certainly does. It took him not more than four strokes for any man. One to engage, one to disarm, one to feign the death stroke, and a whack across the backside for each with the broad edge of his blade! It was a splendid exercise, with—”

“Spare me, Plari!” Chogi begged. It was a request, but the threat in her voice told Plari he had no alternative but silence. He smiled at Chogi, and closed his mouth. “Nevertheless,” Chogi began, turning to her son, “that wonderful ability of yours is of little value here. I wager Doriyth mod Karis could use your blade this minute—if he hasn’t already fallen. I did tell you that he notified us of his lack of water. I know I did.”

“You did?”

“She did,” Sarie agreed.

“Oh, hello, dear.” Pahd smiled lazily. “What are you doing up?”

“The question is, are you going to lie there and just let one of your vassals, whom you’ve sworn to protect, be overrun by the armies of this renegade merchant? Are you?”

Chogi demanded loudly, her face turning orange-red.

“Of course not.” Pahd shrugged. “Then what are you going to do about it?” Chogi shouted.

“I’ll—rescue him, naturally,” Pahd replied.

“When?”

“Well, we could go today—” Pahd began.

“Wonderful!” Chogi sighed and turned to stalk triumphantly from the room.

“—on the other hand, it’s raining today. By the time we got a nice-sized army gathered from the city, it would be late afternoon, and it isn’t good to leave for war in the late afternoon, so probably it would make better sense to wait until tomorrow morning, when it may not be raining and more people would be willing to volunteer.”

“Are you finished?”

Chogi snorted. She leaned in the doorway, waiting for him to make up his mind.

“Why do you always ask me that. Mother? Why can’t you just let me take my time?”

“The army!” she demanded.

“Shall Plari give the order to muster the army or not?”

“Always rushing me!”

“Take your time, darling,” Sarie soothed, kneeling behind him on the rug to massage his neck.

“I think I will,” Pahd said defiantly, leaning back into her fingers and closing his eyes. They popped open again to look at Chogi. “Don’t worry. Mother, I’ll get to it.” Then he lay back into Sarie’s lap.

“If there’s anything left to get to,” Chogi muttered sourly, and she left the armory. As if that weren’t aggravation enough, she slipped climbing the steps back up to the tower.

But there was no rain on Dorlyth’s castle. Though Doriyth pleaded with the powers to send moisture his way, none fell. He stood on the battlements, gazing north at a large black cloud, feeling the promise of rain in the sticky way his robes clung to his body. But the cloud passed him by. And the blue-and-lime tents stayed on the hillside beyond his unplowed fields, awaiting his decision. To fight? Surrender? Where was Pelmen by now? Where was Rosha? Vainly Doriyth watched the storm bypass the boundaries of his lands. His mind was made up. He skipped down a stairway to the stables and found his captain-at-arms.

“It’s time to move,” he murmured quietly, and the captain managed a grin between parched lips.

“I’d drink to that—if there was anything to drink.” Dorlyth nodded. “A general summons, then. We’ll make our plans together.” Across fields now a foot and a half deep in grass, Tohn sat waiting for some sign. Finally his patience was rewarded. “Action on the battlements,” a soldier informed him through the walls of his tent, and he stepped out into the muggy day to see for himself. There was the crisp, clear note of a horn being blown within the walls of his target, and his wrinkled face cracked open into a smile.

“Blow our own horns, lad,” he ordered his squire, and the boy rushed off to deliver the old merchant’s instructions.

“Now what, Dorlyth?” he said softly, unconsciously fingering the edge of the knife he had been sharpening. He glanced down at the knife; realizing its import, he felt a heaviness come over him. He hid the knife within the folds of his tunic, where it would be easy to reach, and ducked back into the tent to prepare for battle. “Funny,” he continued, speaking only to himself, “I used to feel elation when I finally broke a siege. Why is it now I only feel old?” Trumpets began to sound on all sides of him, and he lost himself in the noise and the detail of making ready for battle.

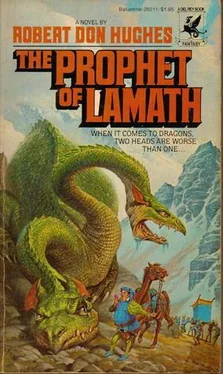

“I wish to see the King,” Peri announced, bowing stiffly. It was not a deep bow. Pezi hated deep bows, for he was afraid someday he would bow so deeply he couldn’t straighten back up again. He looked neither to right nor left, his face frozen into an official-looking frown. There were certain rules of behavior in the Lamathian court, and Peri had studied them all in preparation for becoming a merchant. He concentrated on remembering all of them now. He realized his career depended on how effectively he carried out Flayh’s orders, and that meant he needed to be well received here. But it was difficult for him to keep a confident manner in the rarefied atmosphere of the court of Lamath. It was, of course, no more magnificent than that of Chaomonous—less so—but it was new to Peri, and quite forbidding. The walls were of white marble streaked with veins of blue and coal-black, and they glistened in the light of lamps that burned the purest of olive oil for fuel. Most impressive were the forty-foot dragon statues that guarded every comer and every door. Peri’s last meeting with Vicia-Heinox had left unhealed wounds on his psyche. He didn’t enjoy being reminded of the monster’s existence every forty feet! “You… want to see… the King,” the reply came at length from the vizier of Lamath. When the man said no more, Peri felt a need to fill the silence.

“Yes, I wish to see the King.” There was more silence, and the vizier sneered politely. It was permissible to express any emotion in the Lamathian court, as long as it was done politely.

“You!” More silence. This time when Peri opened his mouth the vizier quickly cut him off. “What possible business would you have that would interest the ruler of the entire world?” It was Peri’s turn to sneer, but he hadn’t mastered politeness. “You might tell the ruler of the world that the King of Chaomonous is preparing to bury him!” The vizier raised an eyebrow, not at the news but at Peri’s breach of etiquette. “What a quaint turn of phrase.” The vizier smiled.

Читать дальше