“That is my mission, cousin,” Pezi replied with insulting politeness. “But first priority is a saddle-maker I know.”

“A saddle-maker?” Someone asked. “Since that thief stole my horse, I’ve had to use one of your skinny little saddles that doesn’t amount to anything. It’s like riding on a rail, I tell you! It’s about to cut me in half.” Someone giggled. “What are you laughing at?”

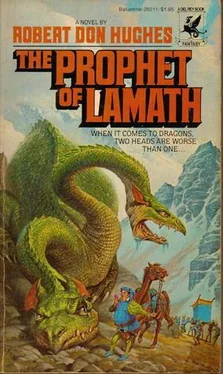

“The dragon has one body with two heads. Can’t you picture Pezi with one head and two bodies?”

“There’s certainly enough of him for two!” someone whooped, and they were all cackling again.

Why fight it? Pezi thought. His sword remained in his scabbard, and he sighed for the passed-up onions.

Pelmen came back to camp before the sun rose, and was there when Bronwynn awoke. A fire was made, and breakfast cooked and eaten, without a word passing among the three of them.

They bypassed the mountain, skirting its base to the east and then back around to the north. Even after they were well past it, Pelmen kept craning his neck to look back at its towering summit.

It was during that afternoon that the dread fell on Bronwynn. She began to believe that things were watching her. The forest had opened up again, and they rode once more in the realm of the big trees. Bronwynn could see long distances in all directions, yet she still felt uncommonly tense. She convinced herself that there were watchers behind every trunk—invisible watchers, who kept hiding behind the trees. She pulled Sharki down off her shoulder and began stroking his feathers. If it annoyed him, the bird didn’t show it. She searched the limbs above for squirrels, but saw none. Except for the three of them, the forest was abandoned. We are riding through the land of the dead, she thought, and a tremor swept through her. She swiveled in her saddle, seeking reassurance from the powershaper who rode behind her, but found no help there. She saw that Pelmen was turned away too—back to the mountain. What fascinated him so about that pile of rock? Then she saw his face as he turned around again, and her heart quailed. His forehead was furrowed with lines of uncertainty, and his normally vibrant eyes looked lifeless and lost. His lips moved. He’s talking to himself, she thought. The powershaper is unsure of his power. She turned to look at Rosha and edged her horse closer to his. The young warrior was fighting to stay awake. The day passed in deathly silence.

And yet when they stopped to make camp that night, Pelmen seemed his old self. He called fire out of the air and made it dance to amuse Bronwynn. He slapped Rosha on the shoulder and taunted him for being a sleepy head.

“You are Rosha Pahd-el, that’s who you are,” Pelmen teased. “You’ve caught the King’s disease.” Rosha grinned wryly, but said nothing of the cause of his exhaustion. He was profoundly grateful finally to see Pelmen kneel in the ritual that would draw a wall of invisibility around them. But his thanksgiving gave way to anxiety again when, more than an hour later, Pelmen hadn’t budged from that position. Rosha sat by the fire and watched his father’s friend, feeling some responsibility to protect the man—and realizing how unequal he was to the task.

“I’ll bet you’re hungry, aren’t you?” Bronwynn asked. Rosha began to reply that indeed he was, but stopped when he saw she wasn’t talking to him but to her bird! “Go on, Sharki. Take off!” She tossed the bird up into the air, even as Rosha was crying out.

“Wait!” The cry echoed away.

Rosha stood slowly, shock and disappointment etched on his face. Bronwynn looked at him curiously. “What’s wrong with you?”

“P-p-Pelmen has p-put up the cloak of p-protection! How will Sharki find us in the d-dark?” Now grief tore through Bronwynn, and she cried, “My falcon! I’ve lost my falcon!” She darted for the edge of the tiny clearing, but Rosha leapt out and caught her by the wrist. “He won’t know where to find me! He’ll be lost!” she said, tears spilling onto her cheeks as she struggled to get away.

Rosha clung to her, whispering to calm her. “We’ll f-f-find him. We’ll step outside the c-c-cloak and wait for him to return!” Then he slipped his arm around her shoulders. Glancing back once more at the kneeling figure of Pelmen, he guided her through that magic wall of chill they had come to take for granted. The fire winked out behind them, and they sat on a fallen log and looked back at the now darkened meadow. There were no stars tonight, nor did the glow of a moon pierce the heavy cloud cover overhead. Rosha drew his greatsword and propped it on the log beside him.

“We’ll be able to see him here?” the girl asked anxiously.

“I g-guess so. I’m no p-p-powershaper, I d-don’t know.”

“I wonder if Pelmen is, anymore,” Bronwynn said, her eyes searching the sky. “Has he talked to you about last night?” Rosha shook his head. “I m-meant to sp-speak to you about that—”

“Slow down,” she murmured, laying a hand on his arm. “You get nervous and then you talk fast, and your stutter gets worse.” Rosha looked at her, a new appreciation of her dawning in him, then nodded and continued, more slowly now. “I—have—been—watching—him—all day. He is—changing.”

“Into what?”

“Into—whatever—he is—in Lamath.”

“That makes no sense. He’s himself, isn’t he?”

“Yes. But—my—father—says—his—self—is different there. He d-doesn’t—he—doesn’t—shape—ppowers in Chaomonous, d-does he?”

“Slowly! No. But there aren’t any powers in Chaomonous.”

“No—powers?”

“I’ve never seen any. But, of course, there are things like lightning and wind. Our learned men don’t call them powers, though, and they don’t try to shape them by magic.”

“Then—how?”

“By—understanding them. Experimenting with them. Mixing things together. You understand, don’t you?” Rosha shook his head. “Sounds like m-magic to me.”

“But Pelmen doesn’t do that there. Or he didn’t, when I knew him.”

“What—did—he—”

“He was a player.” Rosha cocked his head in puzzlement. “He put on plays for all the people to come watch.

He wrote some himself, I think. They were funny plays, until he began to make fun of my father. That’s what caused my father to enslave him.” Bronwynn thought for a moment, then said, “Oh no, he’s not going to turn into a stupid actor again when we get to Lamath, is he?” Rosha shook his head, and partially smiled. “He’s—not what you—think he is.”

“By that you mean—?”

“He’s m-more.” Now it was Bronwynn’s turn to be puzzled, and she waited for Rosha to elaborate. “M-my father—told me, but I d-didn’t—believe him. Last n-night—I—left—you—for—a little while. I followed him. He was—kneeling—like he is n-now. Only he was—talking to someone.”

“Who? Who was there?” Bronwynn asked anxiously, the dread springing again to her mind.

“That’s—j-just it. There was n-no one there!”

“But there’s someone here, laddie-buck!” a voice said behind them, and suddenly Rosha and Bronwynn knew what fishnets looked like to a fish.

The men were experts at this quiet capture, and struggle was futile. Rosha still gave it a try, fighting to get his hands past the rope that bound them within the net and onto the handle of his greatsword. A foulsmelling man kicked the sword and sent it flying well beyond Rosha’s reach.

“Fetch it, laddie-buck,” he laughed, but his laughter froze in his throat. He had kicked the sword into the meadow.

Before it hit the ground, it disappeared. “This meadow is witched!” he whispered urgently. “Let’s take our treasure and begone!” Bronwynn screamed and Rosha fought, but the net was too strong and the hands that held them too experienced. Soon they were both bound hand and foot, and were each carried away by a pair of slaves, their bottoms dragging in the fir needles.

Читать дальше