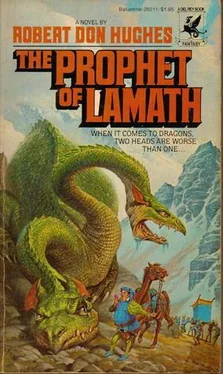

Tahli-Damen watched in amazement. The noise passed as suddenly as it had begun—the dragon cleared the high cliffs, and was into the open sky beyond, no longer visible to the caravan. The merchant gradually became aware of the babbling voices behind him. At last one particular voice got through to him.

“Sir? Couldn’t we—perhaps—move on? Maybe?” It was a slave who was speaking, one who obviously preferred the idea of bondage in Lamath to digestion in the dragon’s belly.

Saying nothing, Tahli-Damen urged his mount forward. Within a few minutes they all reached the level plateau that was the center of Dragonsgate. Then they heard a subtle whir of wings, and once again Vicia-Heinox stood before them.

“Where do you think you are going?” Vicia scolded.

Heinox said nothing, holding back and eyeing the rider angrily. Tahli-Damen hoped Vicia would not turn his back on Heinox—so to speak. It wouldn’t take that other head more than a second or two to swallow the merchant.

“I—thought you—had—” he began lamely.

“We’ve settled our differences,” Vida announced. “That fast?” the rider answered, neglecting to hide the disappointment in his voice. Heinox growled, and Tahli-Damen’s horse backed up three paces, nearly treading on a bewildered slave’s toe.

“Yes,” Heinox snarled. “That fast. I have been forced to admit that an alien presence occupies my body, and that I and it are not the same.”

“There will be trouble when the Lamathians hear this,” Tahli-Damen muttered under his breath.

“Very well,” he spoke out, “what kind of deal do you wish to.

make?”

“We’ll take all of these slaves—” Heinox began.

“All! But you never take all! How can I make a profit if you—”

“You forget,” snorted Vicia. “Now we have two mouths to feed.”

“But you only have one belly!” Tahli-Damen argued.

“It’s the principle!” Heinox snarled. “We get equal shares in everything—until I can figure out how to divest myself of him.”

“It is I who shall get rid of you, Heinox,” Vicia chuckled. “But it may take some time. Until then we share.”

“But—”

the merchant started to protest. “As for you,” said Vicia, “I wish to enlist the aid of your house in dealing with this menace I’m carrying around with me.”

“No!” Heinox snorted, moving in so close behind Tahli-Damen’s back that the merchant could feel the warm breath through his robes. “I must have the aid of Uda! It’s a matter of life and death!”

“You aid him and I’ll eat you,” Vicia said flatly. “You help him and I’ll eat you!” Heinox retorted. Tahli-Damen gulped.

“And if I refuse to help either one of you—”

“We’ll tear you in half.” Heinox smiled.

Tahli-Damen gulped once more. “I hope it doesn’t anger you for me to point this out, but—”

“But what?” Vicia demanded.

“But if you should manage to kill him, you’ll die too.” The merchant looked over his shoulder at Heinox and nodded.

“Yes, it works the same the other way around.” Both heads jerked up and away, and they conversed together in low tones. The merchant looked around. The slaves seemed to have come to terms with their fears of being eaten. The biggest threat now was that the dragon would talk them to death.

“All right,” Vicia said finally after both heads had returned to Tahli-Damen’s side. “We’ve agreed we can’t do anything to one another—yet.”

“But it’s going to be difficult for us—” Heinox interrupted.

“—since we will constantly—”

“—be fighting—”

“—for—”

“—control!” Heinox had gritted his teeth and forced the word in ahead of Vicia. They growled at one another.

“What about business?” the merchant pleaded.

“We have agreed on one thing,” Vicia began. “We hate Pelmen the Player!” Heinox snarled. “Bring him to us!” Vicia roared. “We want him soon!” Heinox screamed. “He’s the one who caused all this!” Vicia bellowed, then cleared his throat and dropped his voice. “Bring Pelmen to us, and we’ll give your house a monopoly on all trade through Dragonsgate.” Tahli-Damen’s eyes flew wide open. “I’ll get on it immediately!” he blurted, and he turned his horse to ride back down to the south, to tell Jagd the news. Already he could see it: Tahli-Damen, Elder of Uda, engraved on a mother-of-pearl nameplate— “Of course,” Heinox whispered, coming alongside him again, “if you can think of a way to rid me of this aggravating growth on my shoulder—”

“I am not a growth!” Vicia shouted. “And you remember, merchant of Uda, it was I who kept you from a terminal case of being swallowed!” Tahli-Damen could see another argument brewing, and he kicked his horse to urge it more quickly down the mountainside and out of the line of fire. Then it struck him. He was abandoning his caravan. He slowed his steed and twisted around to shout at the dragon heads above him. “But what about my slaves? My goods?”

“You just worry about Pelmen,” Vicia said, smacking his jaws together hungrily.

“Yes, do,” Heinox urged. “We can guarantee—these slaves will be well taken care of.”

THE DAY THAT BEGAN so cold warmed considerably as the sun climbed in the sky. Dorlyth’s castle lay far to the north when Pelmen finally yielded to Bronwynn’s plea for a rest. They stopped in a grove of trees, and the girl doffed the heavy coat she’d been wearing, carefully moving the falcon from one arm to the other and back again to avoid disturbing it.

“Why are we going south?” she asked.

“To fool Tohn mod Neelis,” Pelmen answered firmly. He was in no mood for conversation. Surely the girl knew that; he had ignored her questions all the way from Dorlyth’s castle. But she was Talith’s daughter, to be sure. Stubbornness ran in her blood.

“Who’s that, and how will it fool him?” she persisted. “Tohn mod Neelis is the Elder of Ognadzu in Ngandib-Mar.

We’re trying to make him believe we are riding south, to take you back to your father.”

“Why don’t we just fool ourselves instead and go back to my father? If you think he’d imprison you again after rescuing me, then you don’t know him. He’d welcome you as a son!” Pelmen made a face, and Rosha chuckled. By the time Bronwynn twisted around to glower at the lad, he had taken a deep interest in something on his saddle horn, he wouldn’t look at her.

“We’re going to Lamath, my Lady, in spite of your persistence,” Pelmen said. “It’s the safest place for all of us, it appears.”

“Then why are we wasting time going south? Shouldn’t we be headed north as quickly as possible?” Pelmen sighed, and peered out through the trees. He pointed at a small stream that divided a meadow that 95 was yellow with buttercups. “I’ll show you a little illusion when we cross the stream, the same illusion Tohn will see when he follows us here. Perhaps you’ll understand then why Tohn may become a bit confused. Let’s ride.”

“Not again!” Bronwynn complained. “We just stopped!”

“Bronwynn,” Pelmen began sharply, then stopped himself. Maybe Dorlyth was right.

Maybe the girl was more than he could manage.

“Yes?” she asked innocently, eyes wide.

“Let’s ride.” He spoke softly to Minaliss, and the horse carried him out of the trees with a crash of breaking brush.

There was nothing to do but follow him, so Bronwynn urged her horse into pursuit. She had stopped paying any attention to Rosha, since he seemed determined to ride behind her. They all crossed the meadow at a trot, stopping at the water’s edge.

Pelmen turned to look at Rosha. “Ride through, lad.” Rosha was quick to obey. He urged his horse down into the stream, feeling a strange chill from the water, as if he crossed ice instead. Riding up the opposite bank, he turned to Pelmen to await further instructions, and gasped in surprise. His hand went to the pommel of his greatsword; it was out of its scabbard and into the air more quickly than a sneeze. Pelmen and Bronwynn were gone! He kicked his mount and was back into the water. As suddenly as they had disappeared, they were there again.

Читать дальше