Joscelin’s love of the land, my love for Delaunay; these things, I think, along with the good nature of the Friotes and the bold, cheerful manner of my three Chevaliers, won over the folk of Montrève. Once we were at last ensconced, I began to write letters, and Phèdre’s Boys leapt at the chance to play courier, crossing the realm with correspondence. I wrote to Ysandre, with gratitude, to Cecilie Laveau-Perrin and Thelesis de Mornay, with small tales of our doings, to Quintilius Rousse and Gaspar Trevalion, with greetings; and always, with a plea for news. I wrote even to Maestro Gonzago de Escabares, in care of the University of Tiberium, and Remy was gone months on that adventure.

And I bought books, and in L’Arene, Ti-Philippe found Taavi and Danele, owners of a prosperous tailor’s shop in the Yeshuite quarter.

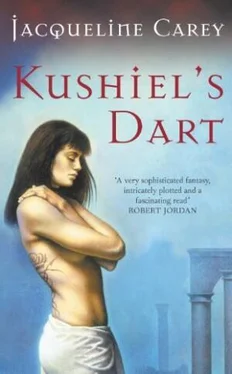

That spring Joscelin and I rode to visit them, and held a happy reunion. Impossible to believe that scarcely a year ago we had met on the road, where they had saved our lives. The girls had grown taller, and our Skaldi pony, still with them, had grown fatter. If they would still accept no reward, I repaid them as best I was able, with a sizeable commission for livery. The insignia of Montrève was a four-quartered shield, with a crescent moon upper right and a mountain crag lower left. That was ever the standard we flew at the manor, but for Phèdre’s Boys, I added my own devices: Delaunay’s sheaf of grain, and the sign of Kushiel’s Dart.

We returned from L’Arene the richer in renewed friendships, and with one addition: Seth ben Yavin, a young Yeshuite scholar who stammered and turned red in my presence, but was nonetheless doggedly persistent in his teaching.

All that spring and well into summer I studied with him, and the days slid by like water. Sometimes Joscelin joined us, but not always; the lure of the mountains was stronger, and he would rather, he declared, learn it from me. As I gained some small proficiency, Seth began to forget I was an anguissette and sometime Servant of Naamah, and grew more at ease in my company, arguing and debating happily.

It was good to have my mind challenged and occupied, for it kept me from restlessness. We had not spoken of that, of what would happen when Kushiel’s Dart began to prick. I was an anguissette; it would. But for now, even I had had a sufficiency of pain.

When deep summer began to give way to early fall, Seth begged leave to depart, having family duties to resume. He left with Fortun to accompany him, a generous purse of his own, and another to accompany a list of books and codices he felt I might need, and for which he promised to search. I had a long way to go in my studies, but I knew enough to begin my quest.

The leaves were beginning to turn gold when Gonzago de Escabares arrived.

He came unannounced, with a lone apprentice tending him, two horses and a well-laden mule between them; a little greyer and stouter, but otherwise unchanged. I threw myself on him with a cry of joy, and he laughed.

"Ah, little one! You’ll give an old man the fits. Come, I’m near starved to the bone. Didn’t my Antinous teach you aught about hospitality?"

I led him into the manor, talking all the while, I am sure, while Joscelin looked on with polite bewilderment and ordered their horses stabled, and the mule unpacked.

Seth ben Yavin had been a paid tutor; Maestro Gonzago de Escabares was my first genuine guest. In an unexpected state of nervousness, I nearly drove the household staff mad with half-brained requests, until Richeline calmly and firmly ordered me to attend to my guest and leave the arrangements to her.

Over wine, which the Maestro quaffed heartily, and an array of cheeses and sweetmeats, which also met a quick end, I learned that he had been traveling in the northern city-states of Caerdicca Unitas, learning of the upheaval along the Skaldic border. An old colleague of his in Tiberium had received my letter, and he decided to pay a visit, bringing an apprentice who wished to learn of de Escabares' method of studying the world.

It had been his plan to return home to Aragonia and begin drafting his memoirs, but upon receiving my letter, he had determined to come first to Montrève, which lay nearly on his way.

"I would have sent word, my dear, but I would have outpaced it," he said, eyes twinkling. "We traveled like the wind, did we not, Camilo?"

His apprentice coughed and hid a smile, murmuring something about a rather slow breeze.

I laughed and patted Gonzago’s hand. "I’m just glad you’re here, Maestro."

After they had retired and rested for a time, we dined, a meal of sufficient rustic splendor that even the Maestro was content. For my part, I ate little, overwhelmed with grateful pride that such hospitality was mine to offer. I knew full well all credit was due to the household of Montrève, and not me; but they had done it on my behalf, investing their pride in mine, and I was grateful.

While we dined, I spun the long story of our journeys, beginning with the death of Alcuin and Delaunay. Much of it, Gonzago knew, but he wanted to hear it firsthand. Tears filled his eyes at the start; he had, in deep truth, been very fond of Delaunay. To the rest of it, told in turns by Joscelin and me, he listened with a historian’s tireless fascination. Afterward, he told us of his travels, and the knowledge he had gleaned. The Caerdicci city-states were falling over themselves to establish trade with the no-longer-isolated nation of Alba, jealous of the status enjoyed by Terre d’Ange and her ally, Aragonia.

By the time our meal was cleared and we were lingering over brandy, the apprentice Camilo’s head was nodding, and Gonzago sent him to bed.

"A good lad," he said absently. "He’ll make a fine scholar someday, if he can stay awake long enough." He rose, ponderously. "I’ve some gifts here for you, if he’s not misplaced them," he added. "I brought a beautiful Caerdicci translation of Delaunay’s verse…pity, I’d have looked up some Yeshuite texts for you if I’d known…and somewhat odd, beside."

"I’ll fetch your bags for you, Maestro," Joscelin offered, heading for his guest-room. Gonzago sank back down with a grateful sigh.

"A long trip on horseback, for an old man," he remarked.

"And I thank you again for making it." I smiled at him. "What do you mean, somewhat odd?"

"Well." He picked up his empty goblet and peered at it; I refilled it with alacrity. "As you know, I was in La Serenissima for some time, which is where my friend Lucretius sought me. I have an acquaintance there, who charts the stars for the family of the Doge. Lucretius inquired for him there, explaining his business. He even had to show the letter, with your seal. They’re all suspicious in La Serenissima." He swirled the brandy in his goblet and drank. "At any rate, my stargazing acquaintance eventually told him that I had gone on to Varro, and gave him the name of a reputable inn. Ah, there you are!" He seized upon the pack that Joscelin brought. "Here," he said reverently, passing me a twine-bound package.

I opened it with care, and found it to be the Caerdicci translation. It was beautiful indeed, bearing a tooled-leather cover with a copy of the head of Antinous, lover of the Tiberian Imperator Hadrian, worked upon it.

Joscelin laughed. "A Mendicant’s trick, if ever there was one!"

"Truly, Maestro, it’s lovely, and I thank you," I said, leaning to kiss his cheek. "Now will you keep me in suspense all night?"

Gonzago de Escabares gave a rueful smile. "You may wish I had, child. Having heard your tale, I have my guess; hear mine, and make your own. Lucretius and his apprentice bedded down at the inn, and in the morning, he found he had a guest. Now, he is an eloquent man, my friend Lucretius; he is an orator after the old style, and I have never known him to be caught short of words. But when I asked him to describe his guest, he fell silent, and at last said only that she was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen."

Читать дальше