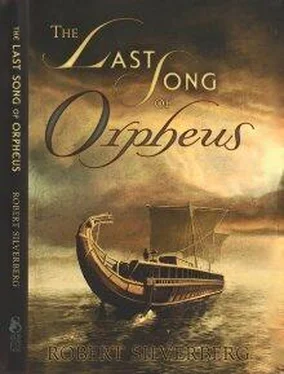

The Last Song of Orpheus

by Robert Silverberg

For Barry Malzberg

Now strike the golden lyre. Bring forth a ringing chord. Another, louder. Louder yet: a chord to raise the dead. Yes, even that: death itself cannot withstand your music. So strike the lyre; raise the dead; make the rivers weep, Orpheus, and the trees shed their leaves in sorrow.

And strike another chord, an even louder one. Then a softer one, and softer still.

Sing, Orpheus!

Sing of your life, and of the understanding of sacred things that has been given to you, and of the tasks the gods have laid upon you, and of your sufferings in pursuit of those tasks, and of your death. And of the eternal renewal that follows death.

Sing!

This will be my last song, which I make for you, Musaeus my son, telling all there is to tell of my life. My last song, but also my first, for in my end is my beginning, and for me there are no ends and no beginnings but only the circle that is eternity. My sense of time and space is not like yours, for I know, better than you, better than any mortal possibly could, that the serpent, Time, curves round upon itself and grasps its tail in its mouth. I stand outside; I contain everything; I perceive the alpha and the omega and for me they do not have the same order of being and arrangement that they do for you. Past, present, future: for me, as for all those who are in whole or in part divine, they are all one indisseverable thing. My yesterdays are my tomorrows, my tomorrows are my yesterdays. It is decreed that I must forever reenact my past, which is indistinguishable from my future, both of them constituting an eternal present. I have lived, and I have died, and I have lived again, and I have died again, and so it will be, repeated and repeated and repeated, world without end.

If I tell you things that you already know, forgive me, for the gods deem it necessary that you hear them again.

I am Orpheus, the son of Apollo. At least it is said that he was my father. I will not deny it. But also people say that my father was Oeagros, king of Thrace, who ruled over the rough unlettered Ciconian folk, and I do not deny that either. I deny nothing; I confirm nothing. But I can at least tell you that beyond any question my mother was the the muse Calliope. It was she who taught me how to make verses to be sung, and Apollo who gave me my golden lyre, which Hermes fashioned for me with his own hands. And so music has flowed from me all my life as though from an inextinguishable fountain, which is to say that there has been music in the world since the beginning of time and that music will endure to time’s end, and beyond it to the moment of beginning again.

I was only a boy when Apollo came to me with that lyre. Not truly young, you understand—I was never young, just as I will never be old—but this was in the time of my life when I was a boy. I lived in Thrace at the court of my father King Oeagros, and the life I led was that of any youthful prince, that is to say, hunting and mastering the games, and attending the rites and sacrifices and later helping to take part in them, and learning how to handle a sword and a spear and a little about the making of verses and the setting of them to music. My father was a rough, remote, thick-bearded man, strong and grim, as kings often are. I was not his only son and he and I spoke very infrequently, though he was as kind to me as he was capable of being. He had dedicated himself to the god Dionysus and we often performed the turbulent rites appropriate to that god, the torchlight festivals and the slaughter of beasts and the chanting of songs and the drinking of wine, and sometimes also the drinking of blood.

Of my mother Calliope I saw very little. She did not dwell at court, but from time to time I was told that she had come to see me, and I went to a cave in the forest that was considered a sacred place to receive her motherly embrace. She was tall and beautiful, very beautiful indeed, a full-breasted bright-eyed woman with long lustrous hair, and there was a special radiance about her that told me even at a time when I understood almost nothing at all that she must be of divine origin. But it remained finally for my nurse to reveal to me that she was one of the nine muses, who were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, and that like many of her sisters she went among mortals from time to time and lay with them and bore children by them, so that the special gifts of the Muses would pass from the Olympians to the race of mankind. Thus she had lured Oeagros to this cave on a day of lightning and torrential rain when he had been hunting and needed sudden shelter, and there she had given herself to him, and I was the product of that union. So said my nurse, at any rate. That was a wondrous moment for me, when I was told that my mother was divine and that I was the grandchild of Zeus.

But there was a greater revelation to come, not very long afterward. I was pursuing a boar in the forest on a dark day when the clouds hung low and thick. As I ran through a dense glade a voice out of nowhere spoke my name, a quiet voice that nevertheless was as commanding as the voice of a hundred kings.

“Orpheus,” it said, and I halted and turned, stunned, and from between two mighty oak trees came a slender golden-haired man of such beauty that I knew him at once to be a god. In his hands he held a lyre of extraordinary workmanship, and I could see the horns of a second lyre rising behind him, strapped to his back. In that same gentle and amazing voice he said, “I have a gift for you, Orpheus.”

He handed me the lyre. I had had a lyre of my own from my earliest years, and fancied that I played it with some skill, but I had never seen a lyre like this one. Its soundbox was a tortoise shell, but a shell of such beauty and perfection of pattern as is unknown in this world, and its frame was not of wood but of gold; and as for its strings—there were seven of them—they were golden too, as were the pegs to which they were affixed. I held my hand above them and my fingers trembled.

“Go on,” the stranger said. “Touch them!”

At his command I touched them—I had always used only my fingertips, never a plectrum, with my lyres—and from it came such a sound as made my heart quiver and lurch in my breast.

There is no sound like the sound of the lyre. It does not pierce one’s ears like the sound of the flute, nor does it shake the hills like a properly struck drum, nor set the heart atremble with warlike impulses like the cry of the trumpet. But it achieves other things, and they are great things, for it is perfect for the accompaniment of the human voice, fitting the contours of the singing tone the way a woman’s body fits a man’s. The subtle shadings of its tone are unmatched in their beauty, and in the hands of a master the lyre catches the listener’s heart and holds it in an unshakeable grasp. The moment I touched this new lyre that the god had given me—for I had no doubt that this was a god—I knew that I would be such a master, and that all the world would yield before the power of my playing.

“It is for you,” he said. “It is the work of Hermes, and there is only one other of its sort in the world.” Which he took now from his shoulders; and he stroked its strings in a loving way and brought from them a music that was like no music mortal ears had ever heard.

In one staggering moment I came to understand that I must be in the presence of bright-shining Apollo himself, and that in some sense I was his son as well as that of Oeagros. He played a melody and nodded to me and I played an answering one, and he smiled—until you have seen the smile of Apollo, you have no understanding of what a smile can be—and he answered my hesitant line with a flourish of his own, to which I replied more boldly, gathering strength and confidence with each movement of my fingers against those golden cords, so that after a time the music that was coming from me was nearly as potent as the one he was offering me. And for a long while we stood there in the secret glade, playing one to another, until I was no longer sure which one of us was Orpheus and which, Apollo.

Читать дальше