The echo of that note rolled, now growing fainter and fainter down the chain of the hills, seemed louder, more imperative, than—the sound from which it was born. No war trumpet’s ring, no temple gong, no sound I had ever heard could compare with it.

So—they had succeeded in opening their long closed door. Their homeland was before them. Theirs—theirs! Not mine—

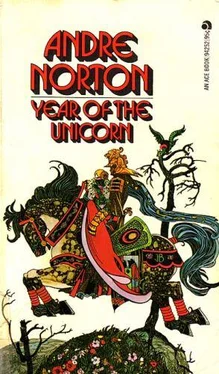

A further rattling of rocks—I looked around. Slavering boar eyeing me, and behind its shoulder the narrow muzzle of a wolf, and the beat of eagle’s wings. The Weremen—or beasts—coming to me. It was my vision from the dead forest brought into the sunlight of open day. And this time I could not flee.

“Gillan!”

A weaving, watering of the pattern. Men now and not beasts. Herrel had pushed to the front of the pack.

“Kill!”

Did that come from the wolf’s jaws, or in the scream of the eagle, or the wild neighing of a stallion? Did I hear it at all, or only read it in their eyes?

“You can not kill—” that was Herrel, “she is sister stock—”

Their heads swung so they looked upon me, and then to him, and again to me.

“Do you not understand what we have netted by chance? She is wise-stock—witch by blood!”

Hyron had come to the fore, was looking upon me with narrowed eyes, noting my dishevelled clothing, the wounds on my hands.

“Why came you here?” His voice was quiet, too quiet.

“I woke—I was—called—” Out of somewhere I chose that word to describe the uneasiness which had impelled me here.

“Did I not tell you?” broke in Herrel. “All of the true blood would answer when we—”

“Silence!” That carried the force of a blow in the face. I saw Herrel’s body tense, his eyes glitter. He obeyed, but only just.

“And you came where?” Hyron continued.

“Up there.” At that moment I could not have raised hand to point. I used my eyes to indicate the rise from which I had viewed their calling.

“Yet—” Hyron said slowly, “you did not fall, you climbed down in return—”

“Kill!”

Halse? Or another? But Hyron was shaking his head. “She is no meat for our rending, pack brothers. Like draws like.” He raised his hand and lined a symbol in the air between us. Green it was as if traced in the faintest curl of mist, and then that green became blue which was grey at its dying.

“So be it.” Hyron spoke those three words as if he pronounced some sentence. “Now we know—”

He did not move towards me, but Herrel did. And I yielded to his hand. Together we walked slowly, none of the Riders following closely behind, letting the distance grow between us.

“Your gate is open?”

“It is open.”

“But—”

“Now is not the time for talking. We shall have many hours for that ahead of us—”

Then he broke the moment of new silence. “I wish—” he began but did not continue, looking never at me but at the way ahead, picking out ever the easiest footing for me.

“What do you wish?” I did not really care much. I was so tired I wanted nothing but to slip into some dark place and there rest content.

“That there was more—or less—”

More or less what? I wondered mistily, not that it mattered. But to that he made no reply.

We came to the tents. The fire was dead, and there were no signs of life—the others must still sleep. Why had I not been able to share that? Since we had passed through the Throat of the Hawk I had shared nothing—nothing—

Herrel brought me back to the bed where the sword had lain between us. Weary I lay down upon it and closed my eyes. I think that I slept—or swooned—because of my great weariness of body and mind.

Had I been adept in the power born in me, but which I used only as a clumsy child would play with a weapon which could either save or harm, then I would have been armed, warned, perhaps able to defend myself against what the new night brought. But Hyron, in that testing, knew me for what I was, witch blood right enough, but unskilled, so no foe to stand against what he could summon and aim.

I had thrown away the one defence Herrel might have set between me and what they intended. Though I was not to know that for long to come.

Hyron moved quickly, and he had the backing of all the pack but one in that moving. Illusions they dealt in—but illusions may be common, or very complex. And the opening of the gate allowed them to draw upon sources of energy which had been dammed from their use for a long time.

I roused as Herrel knelt beside me, cup in his hand, concern in his face, his touch tender. He would have me drink—it was the reviving fluid which had restored me before. I could recall its taste, its spicy scent. Herrel—I put out my hand—it was so heavy—so hard to lift. Herrel’s cheek bearing my nail brand—Why had I so misused one who—one who—?

But that cheek wore no brand! Herrel—cat—Or wax it a cat’s green eyes watching me? Cat-bear—? My eyelids were so heavy I could not hold them open.

But though I could not see, yet still it would seem that hearing had not foresaken me, the dregs of my power leaving open that small channel to the outer world. I could hear movement in the tent about me. Then I was lifted, carried—

I was aloof, apart from what my ears reported.

“—fear him—”

“Him?” Laughter. “Look upon him, brothers! Can he move to raise his hand, does he even know what we now would do?”

“Yes, he will be content enough to ride with us in the morning.”

It was like that beat of their desire in the valley, but now it formed a huge, stifling cloud of will—their will—pushing me down into darkness—with no hope of struggling against it.

The ashen forest about me again—and the hunt! But this was, in its way, worse than it had been before. I looked down upon my breast for that amulet which had been my safety in a sea of terror. This time it did not warm my flesh. I was bare of any defence. Yet I did not run. As once I had said, when fear comes too often, then it loses its sharp edge. I braced my back against one of the dead trees and waited.

Wind—no, not wind, but a purpose so great it sent its force before it as a wind—stirred the leaves which were pallid skeletons of their living brothers. Still did I make myself stand and wait.

There were shadows—but not dark—these were pale and grey and they flitted about, their misshapen outlines hinting of monstrous things. But, as I continued to stand my ground, they only gathered behind the trees, menacing, not attacking.

A wail to follow on that wind of purpose, so high and shrill as to hurt the ears. The shadows swayed and fluttered. Now down the forest aisles moved those who had substance. Bear, wolves, birds of prey; boar, and others I could not name. They walked erect which somehow made them more formidable to my eyes than if they hunted four-footedly.

The need for speech struggled in my throat. Let me but call aloud their names! Only that relief was denied me, and it was as if I suffocated in the need to scream.

Behind the beasts the shadows gathered thickly, their outlines melting, re-forming, melting again, so all that I knew was they were things of terror, utterly inimical to my form of life. Now the pack of beasts split apart and gave wide room to the leader of their company. A long horse head, the wildness of an untamed stallion gleaming in the eyes. And in its human-hands a weapon—a bow of grey-white tipped with silver, a cord which gave off a green gleam.

He who wore the bear’s mask held out an arrow. It, too, was green. A spear of light might have been forged into that splinter shaft.

“By the bone of death, the power of silver, the force of our desire—” No spoken words, the invocation rang in my head as a pain thrust, “Thus do we loose one of three, never to be knotted together again!”

Читать дальше