I swig the rest of the bottle of brandy, then stumble outside in the vast lawn, the alcohol lifting me but I collapse. A light snow. The grass is frozen, prickly. I can smell the earth and wonder how many millions of worms writhe just below the surface, wriggling toward the sky to feast on me if I should die. I lie facedown for hours— What have I done to you? What have I done? Beyond shivering, beyond freezing. My aunt finds me unresponsive but awake—I remember staring into the white sky. What have I done to you? I don’t remember my aunt moving me inside, submerging me in a warm bath. I don’t remember the EMT’s visiting me, I don’t remember anything.

Gav calls.

“Turn on the television,” he says.

Eleven at night, drunk on rum—I turn on the living room television to reruns of Takeshi’s Castle Revival , Japanese women running an obstacle course, their voices dubbed over in Czech. Snow’s fallen heavily the past few days, shrouding the fields. My aunt’s in the barn, the barn lights the only brightness for miles and miles.

“What am I looking for?” I ask Gav, but flip through the news channels and see what he’s guiding me to: “Breaking News. Shootout in Alabama.”

“I’m going to ping my mom,” he says. “Someone should be there with you—”

Helicopter shots of a sprawling farmhouse and acres of fields. Two barns, one of them on fire. A dead body’s in the yard.

“Authorities have ID’d the victim as Cormac Waverly, 36, an Alabama state trooper. At this time, Cormac Waverly is believed to have been one of the assailants in the Theodore Waverly death stream—”

“Dominic, are you all right?” my aunt asks, hurrying inside—she thinks I may have had another episode, a drunken fit or something. She’s relieved to find me sitting on the edge of the couch, even if I do have a drink in my hand. I set the drink down.

“I’m fine,” I tell her. “They found him, it looks like. Waverly. There’s a shootout—”

She takes off her hat and gloves and after a few minutes leaves to brew us tea—a strong Earl Grey that reminds me of Albion, of our first night together. I wonder if she’s there in Alabama.

Cycling the same helicopter shots: circling the compound, black smoke churning from one of the barns, the body sprawled in the lawn just outside the house. The farm is Gregor Waverly’s. Diagrams of the compound, illustrations of the barn fire. The fire started earlier in the day, during the first wave of the assault, when members of Birmingham SWAT established a perimeter. There was an exchange of gunfire. A grenade explosion ignited the barn.

Nearing one thirty in the morning, my aunt makes Cream of Wheat with brown sugar and butter and brews a pot of coffee. The networks recycle the Hannah Massey footage, flashing Waverly’s capsule bio. Footage detailing Waverly’s relationship with President Meecham, extending far back to her earliest days in politics. Talking heads fill in the narrative of the morning’s events—an FBI task force working with private researching firm the Kucenic Group built a case against Theodore Waverly and the Waverly family of Birmingham, Alabama, following the release of the Hannah Massey murder stream.

The Kucenic Group—my old boss appears on television, his white hair and beard growing in wild tangles and braids, looking much more like an avenging prophet than the leader of a private research firm.

“We recognized initial footage as evidence linked to an unsolved case related to the Pittsburgh City-Archive and pursued this lead jointly with representatives of the FBI—”

I wonder what changed—what gave Kucenic courage enough after he’d already abandoned me, after he was so willing to let Hannah Massey slip through the cracks? Maybe the FBI recognized the footage of Hannah’s body, maybe they traced it back to his case file and demanded answers. Maybe the FBI showed up at his door with a bigger stick than Waverly.

Phalanxes of Birmingham SWAT and the FBI assault team snake toward the house, advancing on foot behind armored trucks, eventually moving single file behind men holding steel shields. An explosion rips through the rear section of the house, a fireball that plumes toward the news helicopter covering the siege. Within minutes it’s reported that one member of the Birmingham SWAT was injured in the explosion, an apparent gas leak in the house ignited by gunfire. A few minutes pass and the networks confirm a second death—a man identified as Gregor Waverly, his body recovered. Images of Gregor as a younger man, posed arm in arm with his brother.

Fire trucks and ambulances on scene. The FBI assault team streams into the house. Within minutes they emerge with two men in custody, Rory Waverly and Theodore Waverly, though Rory is reportedly in critical condition resulting from gunshot wounds. Thirty minutes after the arrests, the governor of Alabama holds a press conference, thanking the joint work of the agencies involved. During questions from the press, he confirms that Rory Waverly has died as a result of gunshot wounds sustained in the siege.

Every so often Hannah Massey intrudes on my dreams—I follow the slope down to the riverbed and find Hannah still alive, her body still in the river, half buried in silt. I wonder if I’ll be able to save her, if I can just reach her in time, but in every iteration of this dream the river current kicks up swiftly and carries Hannah away.

“Wake up,” says my aunt, “it’s just a dream—”

I’m fragile now, somehow—I realize that. Physically, I’m fragile and still become exhausted easily. The limping, the difficulty with my hands. Even simple things are still frustratingly challenging for me. The blindness in my right eye has broadened despite further laser surgeries—even on the brightest days there’s a haze that hangs over everything I see. I have trouble sustaining my concentration, even when I’m researching Simka’s case. One afternoon I realize I haven’t made headway for weeks—I realize I’m letting Simka slip through the cracks, so I write to Kucenic—an appeal to continue unraveling Waverly. I describe Simka to him, describe how I believe Waverly was behind the accusations that sent Simka to prison. I figure that Kucenic won’t receive my letter for weeks, or maybe months, as he’s adjusting to his newfound fame—his stream appearances commenting on high-profile cases—but I know that despite the wait, Kucenic is the best hope for Simka. Kucenic will put two and two together, I’m certain. He’ll realize that I’m the only one who can possibly know so many connective details about these cases, but I keep my name out of the letter. I sign as Mook.

General solitude, dedication to poetry. My aunt made an ultimatum—that I stop drinking or move out. She said she’d give me three weeks to make up my mind, but I told her I no longer needed alcohol or drugs, that something had broken inside of me and healed. I resurrected the name Confluence Press for my chapbooks and attend small-press festivals and art fairs, my aunt helping me with the business end of things even though my only sales goal is to break even. After Twiggy’s chapbook, I solicited a Ukrainian poet I’ve long admired for a chapbook and again a poet from Mississippi who’d won the National Book Award a few years ago. I just received confirmation from Adelmo Salomar that I can reprint Ouroboros as a limited-edition chapbook for the fourth book in my line. His letter is postmarked from Chile—I’ve framed it and hung it near my workstation. Everyone I meet is enthusiastic about my craft. I keep my chapbooks to limited runs and have received some positive reviews, even a mention in Poetry magazine in an article about Fine Press books. The attention is appreciated—but I’ve already heard from poets I knew marginally a decade ago, people wondering about John Dominic Blaxton and how I knew him.

Читать дальше

![Том Светерлич - Завтра вновь и вновь [litres]](/books/401288/tom-sveterlich-zavtra-vnov-i-vnov-litres-thumb.webp)

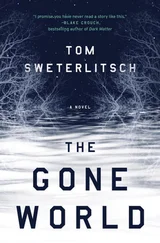

![Том Светерлич - Исчезнувший мир [litres]](/books/420722/tom-sveterlich-ischeznuvshij-mir-litres-thumb.webp)