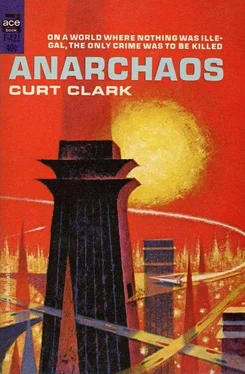

“Those who see by the light of Hell are blind to evil.” Rohstock said that, in his Voyages To Seven Planets. As I rode the shuttle to Anarchaos his words circled and circled through my thoughts, the answer to a question I preferred not to ask.

The shuttle was nearly empty: myself, two other passengers, the steward. Up front were the two pilots, of course, but I never saw them, and so they don’t count.

There is nothing more tedious than a shuttle flight between unimportant planets, even for someone like me, his first time away from home. On a shuttle there is nothing to do, nothing to see; one merely sits in an enclosed tube and is hurtled through hyperspace from here to here, without even the sensation of motion. The only difference between an elevator and such a shuttle is the distance covered. And, of course, the time spent in the voyage.

This one, from Cockaigne to Anarchaos, took four hours. It was the last leg of my journey, and in objective time the shortest, but subjectively it was the longest of all.

I had left Earth five days before on a liner to Valhalla, a three-day trip filled with comfort and luxurious distraction. The customs inspection at Valhalla had taken me by surprise — after all, I was merely passing through their domain — and I had no chance adequately to hide my weapons. They were confiscated, and I was held overnight for questioning. My claim that I was simply a nervous tourist who had brought the weapons along for self-defense was, I suppose, absurd on the face of it; Anarchaos, my destination, was unlikely to attract even self-confident tourists, and the arsenal I’d been carrying was surely excessive for purposes of self-defense. Still, it was the only explanation I would give, and in any case I wasn’t planning to visit Valhalla at all, so the next morning I was — without apologies — released. The weapons were not returned; I would have to get new ones on Anarchaos.

The trip from Valhalla to Cockaigne took seventeen hours. I was saved from boredom by a pleasant conversation with a fellow passenger in the first half of the trip, and by a long and dreamless sleep in the second half.

But now, on this final stage, boredom had me strongly in its grip. I occupied my mind with study of the steward and the other passengers as long as I could, but they were a dull trio, offering little to excite interest or speculation. The steward was male, fairly young, of medium height and weight, blank of face, given to that invisibility or lack of personality common among those in the service occupations. The two passengers, both male, were almost equally invisible; the young, pale, nervously smiling one in the clerical collar was obviously a missionary on his way to his first post, and the older one, with his briefcase and his threadbare dignity, was surely a governmental or industrial functionary of a minor sort, traveling on his employer’s business.

There was only one brief conversation the whole trip, and that between the steward and the missionary. The latter, asking how much longer till we reached Anarchaos, stumbled over the name, smiled apologetically, and said, “It’s a hard word to say.”

“There’s a way to make it easy,” the steward told him. “Start to say anarchy, and midway through switch and say chaos.”

The missionary tried it: “Anarchaos.” The apologetic smile flared again, and he thanked the steward, saying, “It certainly is a name to give one pause.”

“I suppose they meant it that way,” said the steward.

“And their sun,” said the missionary. “Do they really call it Hell?”

“It is Hell,” said the steward.

The hatch was opened, and we three passengers stepped out onto the mesh-sided elevator which would lower us to the ground. Beside me, the missionary blinked and whispered, “Oh, dear! Oh, dear me!”

He was right to be awed. It would take the most intrepid of missionaries not to be awed by his first sight of Anarchaos.

Above us, Hell stood at its perpetual zenith, a swollen red sun, huge and ancient, in the flushed fury of its long decline. Its light was red, rust-red, tingeing everything it touched: the shuttle ship we’d just departed, this elevator and its mesh housing, the flat and nearly empty expanse of the landing pad, the customs and administration shacks across the way, and the distant towers of the city of Ni. So long as Hell stood in the sky, there would be no color here but the shades of red.

The elevator descended, and we were met at the bottom by a slender young man in the uniform of the Union Commission; Anarchaos having no government of its own, the UC maintained a staff at the landing pad here for the assistance and advice of visitors.

“Come this way, please,” he said, without that facile smile of impersonal good fellowship for which the UC is famous; Anarchaos, I suppose, made even official smiles impossible to retain.

We followed him toward the shacks. Behind us, our luggage was being unloaded by other UC men and piled onto a mechanized cart, which buzzed by us before we reached the edge of the pad.

How dreary this world was; walking along with the others I felt weighted down, morose, lethargic. Only with the greatest difficulty could I keep my sense of urgency and feeling of purpose. Already, it seemed, Anarchaos was draining me, sapping my strength.

Our guide led us to a small wooden building, marked on its door ORIENTATION, and motioned us inside, where we found several rows of seats facing a raised platform at the far end.

“Sit anywhere, gentlemen,” he said, and walked down the room and onto the platform. Facing us there he said, “My task, gentlemen, is to acquaint you with some few of the facts of Anarchaos.” And he proceeded to tell us several things which I for one already knew.

That Anarchaos was the only planet circling its sun. That it always showed the same face to its sun, as Earth’s moon shows ever the same face to Earth, so that here there was no night or day in the Earthly sense that I was used to; the city of Ni, for instance, lived in perpetual noon, Hell motionless and unchanging directly overhead. That the planet’s orbit was almost precisely circular, so that there were no seasons here. That humans had colonized it eighty-seven years ago and were to be found only along a narrow band north and south along the sunward face, with Moro-Geth the city farthest to the west and Ulik farthest to the east; at Moro-Geth, Hell stood forever in the attitude of mid-morning, while at Ulik the day was frozen at mid-afternoon. That the night side of the planet was dead and cold and no place for men. That the planet had a deep atmosphere, which constantly drained Hell’s heat to east and west, dissipating most of it on the frigid night side, leaving the day side temperatures well within man’s capacity; at Ni it was Fahrenheit eighty-five degrees and at Moro-Geth and Ulik approximately sixty degrees.

And more, about the humans here; their “society,” if that’s the word for it.

That they had no native government but were maintained entirely by the Union Commission. That they were total anarchists, and yet managed to maintain cities. That they were idealists of nihilism, and yet pragmatic and practical. That individuals should be approached with utmost caution, as nearly anything was liable to give offense. That as there were no laws there was statistically no crime, which merely meant that cheating, stealing, killing and so on were not considered crimes here, or even socially unacceptable.

Читать дальше