"Do you think I don't know places?" he replied, "or the names of them?"

"The first time you came into my bar I saw that though you had been a pilot all your life, piloting was over for you." Antoyne tried to pull away from her, angry that she should express such an intuition, even in the middle of an empty field where no one but Antoyne could hear; even though it was only what everyone knew about him already. "I always understood that," she said. She kept his hands between hers a moment more. Then she let go, because it came to her that they had already left Saudade a hundred light-years behind them anyway. When she looked up at the ship again, it was black and comforting against the afterglow. "In the end, Antoyne, what does it matter to you?" she said.

"Because it means I am not anyone any more."

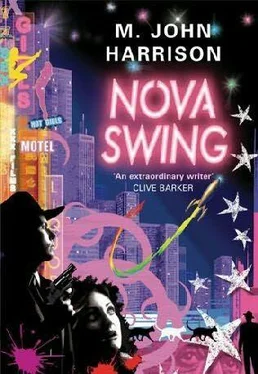

"None of us is anyone any more. We all lost who we were. But we can all be something else, and I will be so happy to fly this rocket anywhere you suggest, even though you and Irene called it Nova Swing, which is the cheapest name I ever heard."

Antoyne stared at her, and then past her. His eyes lit up.

"Hey," he said, "here is Irene now."

Site Crime accountants had followed the money from the back office of the Club Semiramide to a room off Voigt Street, one of the many DeRaad bolt-holes they were rinding and closing daily.

Voigt was full of vehicles and flashing lights. Fire-teams had been deployed. Code jockeys worked on the locked, reinforced door. Quarantine and Hygiene were also in attendance, represented mainly by midrank uniforms, exchanging precedence issues by dial-up while they waited with simulated patience for the action to begin. It was the usual scene, except that a tall, heavily tailored young woman with a forearm datableed had overall charge of the operation. They all knew who she was, but no one trusted her, or understood how she had advanced herself so far so quickly. Since the debacle out on the Lots, they were uneasy working with Site Crime anyway, but their body language and hers confirmed they had no choice.

The lock proved to be mechanical, which no one knew how to finesse. They blew the door off instead.

The teams went in looking confident but feeling nervous. No one wanted to be first at the scene of a big escape. In the event, they were too late. Something weird had happened here, but now it was over. How you would describe it was this: the room stank. It was the same smell, rank and fatty, you got in a quarantine facility, but reduced because it had settled into the fabric-the bare floor, the bed and its foul grey sheets like a disordered shroud, the white walls with their freight of dried human secretions and undecod-able graffiti. The room was vacant, but only just. The Site Crime people all understood this. It was a category of fact they were familiar with. Something had lived here until very recently, but how you described that something-or what you understood by the term "lived"-was very much up to you. If you had been able to stand there twenty-four hours ago, they knew, you might have seen the composite entity formerly known as "the Weather" leave its hiding place for the last time. The door would have unlocked itself without agency, then closed and locked itself again. There would have been silence outside, except perhaps for the strong, calming sound of summer rain, children laughing and running for shelter, the bang of a door further down Voigt. Those sounds would have had, for a second, too sharp an edge. The woman with the datableed checked out the graffiti. She consulted the discreet codeflows rippling up the inside of her forearm. She shook her head thoughtfully.

"You can finish up here," she told Hygiene.

She drove herself back to the uptown bureau at the intersection of Uniment and Poe. There she ran nanocam footage of the other big unsolved mystery in her career.

This impeccable record, assembled by the vanished detective himself and projected across the walls by his shadow operators, left no one the wiser. In the year after the death of his wife, Aschemann had continued his investigation of the Neon Heart murders. All the details were there. They summed to zero. He watched, he asked questions and took names, he went by the gates of the noncorporate port and smelled the money and the violence in the air. He went from bar to bar. ("At one time or another," he told the cameras, with the impish, inturned smile his co-workers had begun to recognise, "all brave men have seen the sky through bars.") He had himself driven to and from the Bureau every morning and afternoon in a pink Cadillac roadster, 1952. He sat in his office with his feet on the green tin desk, and wrote letters to women, and to Prima. Had he killed her? Was he the Tattoo Murderer? The fact was, the assistant thought, he didn't know, any more than she did. All he knew was what Saudade wanted from him: that he be a detective, and have some plan for how that worked. That year, and every year after, he was like a man reassembling himself-not as something new, but not entirely in his own image either. His sense of guilt dated from Prima's death. But his sense of discontinuity dated from marrying her in the first place.

"All crimes," she remembered him advising, "are crimes against continuity-continuity of life, continuity of ownership, systems continuity."

She sighed.

"Switch this off," she ordered.

Not yet midnight. It was too soon to visit the tank farm on C-Street. The office blinds were down, admitting erratically pulsed strips of neon light, rose-pink and a lively poisonous blue. The furniture smelled of authentic furniture polish. Every so often the assistant said something into her dial-up. Or the shadow operators fluttered close, murmuring, "If you could just sign this, dear." Or they pulled themselves about on the desk in front of her like grounded bats, through the jumbled papers and stripes of neon, hoping that she would notice them. Data ran down the inside of her arm. It was her office now. She had a major escape to deal with. She had operations of her own. She could wait another hour before she made her next move. She could wait another hour after that. But she was restless and didn't know what to do this minute. Damp winds chased wastepaper across the intersection outside, to where a lost blonde stood in her short white dinner frock, smiling vaguely at the deserted pavement and holding both her shoes in one hand.

***

Another month passed, the Nova Swing completed her refit. They had port authority approval. They had a new paint job. They had a company name, Bulk Haulage, thought up after hours of numb effort by Antoyne; and a corporate mission statement which Irene discovered written on her heart, "Aim to the Future." They had hot new upgrades in the drive train. Early one wet autumn day, with rain lashing across Carver Field, Liv Hula heated up the rocket engines, swallowed the pilot interface with the usual combination of optimism and self-disgust, and with Antoyne strapped in the second chair, went all-out for the parking orbit.

"Shit," she was saying five minutes later, her voice issuing eerily from the ship's speakers. "It works."

"Isn't that something," agreed Antoyne.

They stared out at space a moment, then at each other in wild surmise. Space! Tests on the infrastructure showed what they already knew. "It's a tub but it actually works!" Scared and elated, anxious, yet somehow secure in their professionalism, they scuttled for home, where they found Irene the Mona looking pale but happy in rose-pink pedal-pushers, refreshing her make-up from her little shiny red urethane vanity case Antoyne remembered so well. "So does it work?" she wanted to know. During the take-off, she admitted, she sat in the administration building bar with a White Light sundae and didn't even dare watch. "But I saw the flash went over everything. You lit up the rain, I got to say that. I had my legs crossed for you."

Читать дальше