Grahvos avoided the question. “Your Majesties, the High King has no desire for a battle himself. He has empowered me to speak for him in saying this: if Your Majesties will join forces with him, you may retain both your lands and your titles …”

“Be Zastros’ lickspittle in my own kingdom?” interjected Zenos. “No, thank you, my lord!”

“Then we’ll crush you.” Grahvos sounded confident, but a brief scan of the man’s surface thoughts showed Milo much confusion.

“Brave words,” said the High-Lord gravely. “Spoken by a man of proven bravery; but your position is untenable for long, Lord Grahvos … and I’m sure you know it.

“Your army has no boats, and you saw how solid is the wall blocking the bridge. We got those stones by destroying the only ford between here and the mountains. Of course, you could fell trees and try rafting. My catapult crews would be most gratified to see such an attempt … they’d also like to see an attempt to build a floating bridge, if you had that in mind.

“No, Lord Grahvos, your king sits at the end of a very long and most tenuous supply line, deep into hostile territory. His army has already suffered the loss of thousands by the activities of our partisans. Entire units have deserted and marched back to your homeland and, I understand, camp fever has incapacitated more thousands. It might occur to your king to send for his navy.”

Grahvos started. That very thought had been on his mind.

Milo grated. “Forget that thought and persuade your king to do likewise. I had hulks towed from Kehnooryos Atheenahs and scuttled in the channel just west of the Lumbuh delta. There is but the one channel and your dromonds could never negotiate it… now.

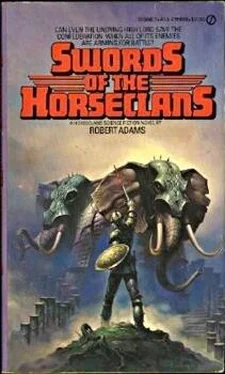

“The longer you sit on the south bank, Lord Grahvos, the higher will be your losses—more men and units will desert, more will be ambushed or killed in raids, more and more will die of disease. Any attempt to cross the river, by any of your available means, will be fatal to the troops employed.” And it was, to almost all of them. The first… and last… assault was launched just after the next day’s dawning. First onto the bridge came two elephants, sheathed from head to foot in huge plates of thick armor that turned the six-foot darts as though they had been blunt children’s arrows. A sixty-pound boulder struck a massive headplate with a clang heard the length of the bridge, but the beast halted only long enough to trumpet his pain and displeasure, then came slowly on. It was then that Milo gave the order to fire the bridge.

The undersides of the logs making up the new roadbed had been thickly smeared with pitch and the interstices packed with tarred oakum and other inflammable substances and the first firearrow began a conflagration which, aided by a fortunate wind, was soon sweeping south, preceded by smoke from the green wood.

The elephants, scenting the oncoming danger, first tried to turn, then to back away, only to be met by countless spear points. Finally, with the fire a bare five feet distant, the eastward elephant splintered the heavy rail and plunged into the river, sinking like a stone. Given room, the other spun about and plowed through the close-packed troops, leaving a wake of mangled flesh and crushed bone.

Miraculously, the other elephant came plodding out of the river onto the north bank, just downstream of the siege-engine emplacement. Milo tried to mindspeak the animal,… and was surprised when he succeeded.

After a short period of wordless mental soothing, he asked, “What are you called, sister?”

“You not … of my kind,” It was half statement, half question.

Milo had had other experiences with animals that had never been mindspoken, and these guided him. Beckoning a couple of Horseclan mindspeakers, he gingerly approached the huge, dripping, mud-slimed beast. There was no longer a battle to require his supervision. The attackers were in full retreat before the fire … those who could walk, run, or hobble; the rest were roasting on the bridge or drowning in the river.

When the elephant saw them, she quickly rolled her trunk out of harm’s way, confused thoughts of battle-training flooding the surface of her mind.

It was obvious that the headplates partially obscured her vision, so Milo took pains to stand where she could clearly see him, motioning the others to do the same. “Sister, we do not wish to hurt you. Why do you wish to hurt us?”

He commenced the soothing again, this time joined by the two clansmen. Gradually, the trunk uncurled, then sought one of the sideplates and gently tugged at it. Her mindspeak was plaintive. “Hurt. Take off?”

Endeavoring to exude far more confidence than he felt, Milo paced deliberately to the cow’s side and began unbuckling the indicated plate. He started as he felt the finger-like appendage at the end of her trunk touch him, but its touch proved tender as a caress, wandering over his body, front and back, head to toe. He was straining to reach the topmost buckles when the trunk closed about his waist and lifted him high enough to reach them.

Seeing this cooperation, the two clansmen came up and began to help. A half hour saw the cow stripped of a quarter-ton of plate and thick mail. Milo was at first appalled at her condition—she seemed bare skin and bones, her ribs clearly evident—and then he recalled that long, long supply line winding through forageless countryside and constantly menaced by his raiders; Zastros was having enough trouble feeding his men, not to mention his animals.

He turned to one of his clansmen. “Rahdjuh, ride to the castra and tell them to get any horses away from my pavilion. Captain Portos says our sister’s kind afright horses; I’m willing to take his word on the matter. Then ride on to the quartermaster and tell Sub-Strahteegos Rahmos to send a wagonload of his best hay and five or six bushels of cabbages to my pavilion immediately. Understand?”

“Yes, God-Milo.” The clansman took off at a dead run toward the picket line.

Milo turned back to the cow and rubbed a hand down the rough, wrinkled trunk. She brought the trunk up, resting its end on his shoulder. “Sister, I wish to help you. I know that you need food, much food.”

She again responded with the plaintive mindspeak. “Hungry … hungry many days. Good two-legs brother will give food?”

Milo beckoned the clansman to him and placed his arm across the smaller man’s shoulders. “Sister, this is my brother, and he is good. He will take you to much food.” He projected a mental picture of bales of fragrant hay and baskets of green-and-white cabbages.

The young clansman stood still while she subjected him to the same examination earlier afforded Milo, but he gasped when she suddenly grasped his torso, lifted him high off the ground, and sat him straddling the thick neck just behind the massive head. “Which way food?” she demanded.

Milo chuckled at the expression on the clansman’s face. “Well, Gil, have you ever bestrode a bigger mount?”

Gil relaxed, grinned, and shook his head. “No, God-‘ Milo, nor has any other Horseclansman, I think. She… and I… we are to go now to your pavilion?”

“Yes, Gil, and since she has accepted you, you are now her brother … and her keeper.” He glanced at the blazon on the young man’s cuirass, the broken saber, and ferret head that proclaimed him a scion of Clan Djohnz. “Tell Chief Tchahrlee that you now have no other duties but to care for our sister here. Now, take her to the food; those bastards over there have been starving her.”

The night after the abortive assault, a score of biremes crept upriver, their oars muffled. Avoiding the larger camp of Zastros, they staged four almost simultaneous attacks on as many camps, while a force of swampers struck the easternmost camp and a strong contingent of mounted irregulars brought fire and sword to the rear areas. The swampers, unaccustomed to fighting in the open, took heavy losses, but the casualties of the pirates and the mountaineers were minimal. The swampers did not attack again, but the reavers and the mountainmen did, three more nights in a row, never striking the same camps.

Читать дальше