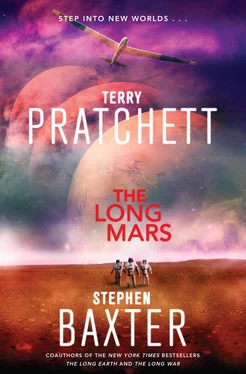

On the Long Mars as on the Long Earth.

She was trapped in a cage one world thin.

As she descended twenty miles.

Into the dark.

Towards the unknown.

It came as a relief when Willis switched on lights, shining front and back of the glider and to either side, picking out the wall on the one hand and the cable on the other. The floor was still too far below to be visible. The wall of the pit was layered, with a spray of sun-blasted dust on the surface, then a mass of rubble and gravel and ice – and then the bedrock, itself deeply cracked, a record of the huge primordial impacts that had shaped this world. She wondered if these walls had needed some kind of consolidation, to keep this tremendous shaft from collapsing. Maybe Mars’s lower gravity, and its cooler interior, helped with that.

‘Piece of cake,’ Willis said as he piloted the glider. ‘Just got to hold her steady. And get used to the thickening air. Worst danger is I’ll fall asleep at the wheel.’

‘Don’t even joke about it, Dad.’

‘You keep watching, the walls, the ground. I have cameras working and other sensors, but anything else you spot—’

‘I can see something.’ The wall, in the plane’s spotlight, was no longer featureless, she saw. The rock face, as rough as ever, was etched with a kind of zigzag spiral. ‘Stairs,’ she said. ‘I see stairs. Big ones, four or six feet deep, it’s hard to tell from this vantage. But they’re stairs, all right.’

‘Ha! And we’re not a mile deep yet. Should have anticipated stairs. A culture careful enough to build this hole in the ground in anticipation of its entire civilization collapsing was always going to install something as simple as stairs.’

‘Why don’t they reach all the way to the surface?’

‘Maybe they just eroded away. I have the feeling this pit has been here a long time, Sally.’

After that, for a time they descended in silence. The circle of Martian sky above them receded, a coppery disc, like a coin. From above, the ship must look like a firefly spiralling down the barrel of a cannon. Still the base of the pit was invisible.

At about twelve miles deep Sally thought she saw more detail on the wall, and she had her father level out for a closer look.

‘Vegetation,’ she said, watching carefully as the glider slid past the walls. ‘Stumpy trees. Things like cacti. Dad, this is like what we saw on Gap Mars.’

He checked the air pressure. ‘Yeah, we’re up to about ten per cent of a bar already. I guess this is the lower limit of tolerance for that vegetation suite. And there must be just enough sunlight down here to support their kind of photosynthesis. Remarkable, isn’t it, Sally? We keep seeing the same biospheric suite, essentially, taking its chance wherever it can, wherever the environment lets up its stranglehold, even just a little. I can feel the air thickening, getting kind of bumpy. . .’

So it was. Sally guessed that the pool of air trapped in the pit was turbulent, stirred up by the heat from below and falling back when it cooled. She tried to watch for more evidence of life on the walls, but mostly she monitored the glider’s increasingly ragged descent.

‘OK,’ Willis said at last. ‘Less than a mile to go. Pitch black down there. Radar’s showing ground. I’m going to put her down on as smooth a patch as I can find – and not far from that anomalous metal heap I detected from the surface.’

She stayed silent; she could only distract him. She checked the seals of her own pressure suit, and telltale sensors monitoring Willis’s suit.

Only in the last few seconds did she see details of the pit bottom, which looked as if it was encrusted with life, a multitude of shapes and colours gaudy in their panning lights, quickly glimpsed. It was like a seabed, like looking down into a fish tank.

‘Here we go . . .’

The landing was bumpy. Through the fabric of the craft Sally heard scrapes, crackles, liquid noises, before they came to rest.

Willis glanced back over his shoulder at her, and grinned. ‘Once again, a piece of cake. Come on, let’s see what’s out there.’

Sally clambered cautiously out of the glider.

The only light came from splashes from the glider’s floods. The disc of sky, far above at the top of this rock chimney, was too remote even to see – although, glancing up, following the blue thread of the beanstalk cable, Sally thought she saw something moving, falling, occluding what light there was.

The ground, as she’d glimpsed just before the landing, was coated with life, most of it static: purple-green bacterial slime, and things like sponges, things like sprawled trees, things like banks of coral. The glider, on landing, had cut parallel tracks through all this, tracks that glistened, moist. The air was comparatively thick, the place was comparatively warm – this was indeed as welcoming an environment as she’d found on any Mars so far. And it surely had to be fed by energy supplied by mineral seeps from the deeper ground, moisture perhaps leaking from some aquifer; there could be no meaningful input of sunlight down here – and no rain, on a typically arid Mars. Unless the pit had some kind of microclimate of its own, she thought, with captive clouds and rainstorms all contained within its walls.

Walking away from the glider towards the elevator cable, she turned her head from side to side, sweeping her helmet flashlight. Aside from the cable itself, and the basic architecture of the pit, there was no sign of structure, of sentience—

Something moved, cutting across her beam from one pool of shadow to another. She whirled, alarmed.

It was a crustacean, she saw, flat to the ground like those she’d seen at some of their early stops, its chitinous armour gleaming with colours that must be, normally, entirely invisible. Indeed it had no eyes, she saw, none of the eye stalks she’d noticed on those surface creatures.

‘You poor thing,’ she said. ‘You really have been down here a long time, haven’t you? Long enough not just for your culture to have fallen apart, but for you to have evolved out your sight . . .’

The creature seemed to listen. Then it scuttled back into the dark.

Keeping a wider lookout Sally walked on, heading for the cable. Even from here she could see that there was no obvious root station, no structure; the cable just seemed to sink into the deep rock, which was covered by a tide of dark-adapted life . . . But, she saw, the cable itself was scuffed, frayed, only a few yards above the ground level.

‘Hey, Dad.’

‘Hmm?’ As ever, Willis sounded distracted, not quite paying attention to her.

‘Bad news is the root node is buried somehow. I suppose if the builders had the power to melt out this pit, they could have just sunk the node in molten rock . . . Good news is the cable is frayed here. Like something clipped it. We might be able to get your samples after all.’

‘Uh huh. And I think I’ve found what did the clipping. Come see.’

She turned, sweeping the glow of her helmet light. She saw Willis in his suit, standing straight, his back to her. He was holding something, in the shadows. And beyond him, nearer the pit wall, she saw a gleam of metal.

It was a spacecraft. A stubby nose and part of a wing poked out of the heavy clay, badly damaged. And she saw scrapings, where Willis had cleared dirt from around a hatchway.

‘What the hell?’

‘Recent,’ he said. ‘Comparatively. Given that the ship hasn’t yet eroded to dust. Maybe they came from some other world – the Earth of this universe, even. Whatever, they must have tried to land down here—’

‘They were even worse pilots than you.’

‘They actually clipped the cable . What if they’d cut it entirely? We could have lost everything.’

Читать дальше