“Well, let’s get on with it then!” said the older child a bit huffily, and started walking into the forest. “Fuck it all!”

“Wait up,” said Cuthbert. “Drystan! No!” But Drystan didn’t stop.

“Come on, tittybaby.”

“Shut.” Cuthbert didn’t like naughty words, but he never threatened to tattle on his brother. The consequences were too severe.

The younger boy trotted behind, still carrying his prophylactic branch.

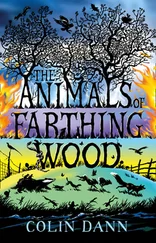

For a while, they combed through a sunny, flat grove of Scots pines. All these softwoods were tall as streetlamps and planted in precise, bright gaps of twelve feet or so. They weren’t native to the forest but had been flash-planted in recent decades to counter vast losses of hardwoods and prevent flooding of the Severn. The smell of pine and rainy loam made Cuthbert feel secure. He and Drystan walked with sure steps over a homogeneous carpet of oranging pine needles, springing a little with each pace.

“A’ve had enough, Dryst,” said Cuthbert. “I wanna go back.” He tugged Drystan’s hand with hot slippy fingers. “I dunna want to see any — you know — them Boogles. I don’t need to see them.”

“Oh, come on, Cuddy,” said Drystan. “Just a little more. There ain’t no bloody Boogles.”

“Don’t say ‘bloody.’ You’ll get a smack from Mum.”

Drystan said, frowning sadly, “What could I get worse than what paerstins *I’ve already ’ad from the Devil himself? That bastard.”

Cuthbert didn’t argue. He had seen Drystan treated worse than a dog by their father — hit hard with broom handles and belts and punched in the stomach. Drystan claimed their father had even once pushed him down the steps at their house, and Cuthbert, skeptical at first, eventually realized it was probably true.

The pines stopped and they found themselves wandering into a more open and varied oak and birch glade. This was the proper, ancient Wyre, before the great woodlands were turned into hunting chases. Here and there grew huge cherry trees and big-leaf limes. The air felt cooler on their faces, but it was trickier to walk. While many old footpaths traversed the forest, some of them trod for hundreds of years by locals, the two boys somehow managed to avoid them all. But it was growing darker, and Drystan seemed disorientated.

Cuthbert said, “We’re lost.”

“We’re bloody not,” said Drystan.

They were walking down into an enormous, strange furrow, about ten meters by one and another meter deep.

“It’s like a giant’s grave hole,” said Cuthbert, fearfully.

It was filled with yellow primroses and ferns taking off in the bowled moisture at its base. It was an old saw rut from the nadir of the deforestation days; indeed, decades before, brave boys roughly the same age used to crawl below the massive circular blade to clean sawdust out. Just when Cuthbert and his brother emerged from it, Drystan hissed, “Stop! Look!” About fifty meters away through a stand of young oak seedlings was an enormous fallow buck, grazing. The two children froze. The animal’s great rack spread like a huge bone map of anger, an inscape of worlds Cuthbert never knew. After a moment, a retinue of does finally appeared, sniffing carefully, nibbling leaves. The buck stared at Cuthbert with ruthless indifference, and the children were afraid and fascinated.

“Has he got a cob on *or summat?” asked Cuthbert. “’E looks like he wants to get us.”

“No,” said Drystan, shoving the anxious word out of his mouth, his voice trembling. “E’s just like a sort of horse or summat. Don’t be afraid.”

“I’m not scared,” said Cuthbert. He said then, in a rather serious tone, as if Drystan was supposed to note this for eternity in the scribbled annals of their youth, “This is the best day I’ve ever had.”

When one of the does ran off, it leaped through the forest with a silent but powerful grace and compactness, like a great red-brown stone skipping along a lake of green. The boys remain transfixed until it vanished. The rest of the bevy held in place, still as statues, like eternity broken into dun-colored pieces shaped like deer.

“I loik this Wyre,” said Drystan.

They took a wide circular path around the animals, crossing through painful nettles and holly patches and over several crisscrossed fallen logs. The forest grew very thick with red-berried rowan and silver-barked wild service trees. It slowed them down. Under the forest canopy spread many grotesque, splaying treeforms caused by the intensive coppicing over the centuries by peasants cultivating cordwood. The coppiced monstrosities looked like colossal flower-heads made of spindly sticks.

As they ambled along, Drystan, at one point, stopped moving, apparently paralyzed by fear.

“I stepped on a snake!” he cried to Cuthbert. “I killed it. It’s such bad luck!”

The two boys inspected the snake and buried it, but the incident obviously disturbed Drystan, and he refused to touch it. He wore an expression of real sadness. It was something Cuthbert never forgot — the death of the adder, before the tragedy, how it seemed to crush Drystan and how he couldn’t stop crying until Cuthbert threw a juicy chunk of coal at him.

They had picked up the pace then, and tried to forget the adder. Cuthbert was having fun, whacking hairgrass and ferns down with his condom stick, as if plying a Congolese rain forest.

After a nervous, exhilarating hour, the sunlight was beginning to fade. They started frankly to run; despite Drystan’s brave words, the prospect of getting caught in the Wyre after nightfall scared them. Worse, if too late, they knew there would be trouble once they got back to the cottage. The belt might come out.

As they ran through the Wyre, Drystan seemed more agile, humming to himself as he hopped over rocks and brush piles and lost antlers and the scat of badgers and stoats. “I’m a deer!” He flowed as a boy-sirocco, crunching down branches and grasses, as fast as the footwork of Roy Race on the football pitch, as dangerous as Dan Dare dashing across a Venusian no-man’s-land to do battle with the green Mekon. He was giggling, couldn’t seem to stop.

“It’s funny this — funny, funny, funny,” he cried. “Kill the Mekon, kill the Mekon!” he was yelling.

“Wait!” screamed Cuthbert, breaking into giggles that slowed him down. “Wait for me!” They charged up and up and up a worn-down red-sandstone escarpment, and dolphin-arched over it, and then they crossed to a half-dissolved railroad track that hadn’t been used for a hundred years, and they roved steadily downhill now, their knees wobbly and ticklish and bending so easily. They were laughing their heads off. The trees were centuries old, taller, the ground entirely grown over with vines and maidenhair and bracken of all sizes and shapes, and everything at heights never any less than their knees, and they ran and laughed and ran and laughed and it was as if they were beating a path through a flood of green and fields of glee that would go on into the millennia.

Then, Drystan disappeared.

Cuthbert foot-planted to a stop. He sucked air in great gobs, his tiny lungs heaving, still grinning. He said, “Wha?”

Where was Dryst?

His brother had simply dropped through the floor of the forest. That’s what Cuthbert saw. So overgrown was this section of the forest over the less acidic soils around Dowles Brook, that the tributary — coursing fast and wide and flush with rainwater from heavy recent storms — was completely obscured.

He ran a few steps more, and then Cuthbert was shouting out in pain and terror, smacking and rolling down a precipitous bank into a brook engorged and irate, the water pressing against him like icy stones. Neither city boy could swim. Little Cuddy grabbed at branches and grasses, but they were all too slippy or too slight or they cut into his tender boy-fingers. All at once, water rushed up his nostrils and into his mouth. It was sweet-tasting and cold but thick with flora and bugs.

Читать дальше