Throughout most of the war, the Narseil were allied with the Centrist Worlds—not because they particularly wanted to be involved in the conflict, but because they thought the Centrist Worlds were the most stable. The riggers of the Narseil Rigging Institute had long been developing interesting new synergies with the riggers of the Centrist Worlds, something the Kyber worlds found a threat to their own hoped-for dominance in starfaring science. “But in the end,” El’ken said, and his voice tightened until it was clear that his words were underlain by a very old anger, “the Centrists decided that a fragile alliance with a nonhuman species was less important to them than ending the costly war. They broke their alliance with the Narseil, in exchange for concessions from the Kyber. On the surface, the Kyber surrendered the fight—but in reality, the Centrists weakened themselves, without even realizing they had done so. Without the shared skill and knowledge of the Narseil, they could never reach the Cluster of a Thousand Suns—not in a practical way. They’re too distant; the undertaking too expensive. But by the time the Centrists realized this, the will to attempt such things had withered away in the long aftermath of the war.”

“But why such an abrupt shift—if the Narseil were allies—?”

El’ken waved away the question. “There were numerous small events, and much racially-motivated suspicion. But what finally provided the excuse to break the alliance was the disappearance of Impris .” El’ken gazed up through the star-dome for a moment, then continued with a sigh. “The Narseil were accused of hijacking the ship in order to obtain details of strategic technologies supposedly carried by one of the passengers. There was never the slightest evidence of any such technical secrets, on or off the ship. But most of humanity was all too willing to believe the accusation. You might find some of the writings of that period interesting. They could teach you a lot about your own people.”

Legroeder wasn’t sure he wanted to know.

“By blaming the Narseil for the loss of Impris , the leaders of the Centrist Worlds were able to justify excluding my people from the colonizing effort that everyone assumed would follow at the end of the war. And by doing that , they unwittingly strengthened the position of the Kyber worlds—the very people they were fighting. Such was the price of the peace.”

“I don’t see—” Morgan began, but was silenced by a sharp glance from El’ken.

“That was the end of collaborative rigging between the Narseil and the Centrist Worlds. It left my people impoverished from the collapse of trade, and the Centrist Worlds a parody of their former power and vision. And history was written to perpetuate the lie.” El’ken’s voice grew even sharper. “Who knows what technologies went undeveloped, what areas of knowledge untapped, because of the breakup of that alliance—particularly rigging knowledge , which not only might have taken us to new star clusters, but might also have helped to explain such mysteries as the disappearance of Impris herself? Who knows! And yet, look at the Kyber worlds, which supposedly lost the war. Their expansionism was restricted, for a time. But they have not remained idle—no.”

“But we hardly even hear about most of the Kyber worlds anymore,” Harriet said.

“Perhaps not. But they haven’t gone away. They’ve changed some of their names, to be sure. And they work in other ways now. But they are not idle.” El’ken laced his long, green fingers together and gazed down at his folded hands, in contemplative silence.

He looked up again. “It was a shrewd maneuver by the Kyber leaders. They would have lost the war anyway, had they continued to fight. But by breaking the Narseil-Centrist alliance, they crippled the growth of the Centrist Worlds’ power and influence, even while appearing to cede victory to them.”

“You mean, by undercutting the Centrists’ joint explorations with the Narseil?”

“Of course,” said El’ken. “But it wasn’t just a matter of lost technology. The collaboration had served as a catalyst, inspiring new efforts. Now, with that gone and the real costs of the war hitting home, many of the Centrist Worlds became insular, more concerned with their own economies than with huge investments in exploration, which might not pay dividends for decades. Many, like Faber Eridani, went through their own post-war upheavals, further undermining the preservation of truth. You can read my own writings on the subject, if you wish to know more about it.” El’ken’s eyes again seemed to focus elsewhere. “Among my people, bitterness lingered long after the war’s end. For many years, the Narseil drew away from humanity.”

“But there’s commerce now,” said Harriet.

“Yes— now . But not nearly what we once had. Tell me—how were you greeted, when you arrived here?”

“Like dogmeat,” Legroeder said.

“Not with great friendliness,” El’ken conceded. “Yes, commerce has been renewed, haltingly. But how much has been lost between the cultures as a result of the betrayal? How much trust? Intellectual exchange? How much fruit of cooperation? What knowledge might have been gained if we had explored the Cluster of a Thousand Suns? It is incalculable.”

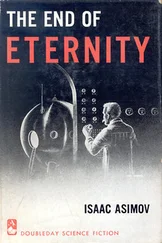

El’ken abruptly stood up. Breathing huskily, he returned to his mist unit, where he stood facing the pool. Legroeder watched Harriet making notes in her compad. When El’ken seemed in no hurry to return, Legroeder got up and walked to the edge of the cavern dome and peered out into space. It all seemed so changeless out there. But he knew it was not. Though it was invisible to the eye, the expanse of interstellar space was laced together by the powerful currents of the Flux. Impris is out there somewhere, he thought. The Flying Dutchman of the Flux… marooned in eternity.

El’ken returned at that moment, picking up as though he had never paused. “It is my belief that descendants of the Kyber are using Impris even now, for their own purposes.”

“Meaning—?”

“Do you have to ask? You, of all people?”

Legroeder’s voice caught. He had never, in seven years with the pirates, been privy to information about Impris . But he’d heard rumors—as had McGinnis. And he had his own capture as evidence. “I know what I think. I want to know what you think.”

“Fair enough. But first, let me ask—do you know who the pirates of Golen Space really are?” The Narseil turned from one to another, his gaze probing. “Any of you?”

Harriet remained silent, though obviously troubled by the question.

“I can tell you who they are,” Legroeder said savagely. “They’re scumbags who prey on the innocent and practice slavery. You want their names? I could give you some, but it wouldn’t do you any good. They’re a long way away.”

“So they are,” said the Narseil. “But that’s not what I meant. I meant, who are they as a people? Where do they come from?”

Legroeder shrugged. “All over the place. A lot of them start out as captives, and get converted, or tortured into cooperating—or—” he tapped his temple “—they get implants, and they don’t have the strength to resist the way Robert McGinnis did.”

“Indeed. But I’m talking about the core population. Do you not know? I’m talking about the Free Kyber—the descendants of the Kyber revolution.”

Legroeder’s mouth opened, but it took him a moment to find words. “Free Kyber? Are you saying that the Kyber worlds are the sponsors of the pirates? ” He suddenly remembered Jakus saying something about the Kyber. Kyber implants.

Читать дальше