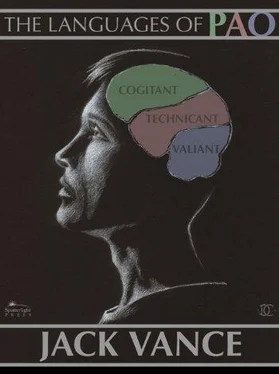

In the great cool halls, full of green leaf-filtered sunlight, children of all ages lived to the sound of the Technicant language, and were instructed according to a special doctrine of causality in the use of power machinery, mathematics, elementary science, engineering and manufacturing processes. The classes were conducted in well-equipped rooms and work-shops; although the students were quartered in hastily erected dormitories of poles and canvas to either side of the monastery. Girls and boys alike wore maroon coveralls and cloth caps, studied and worked with adult intensity. After hours there were no restraints upon their activities so long as they remained on school grounds.

The students were fed, clothed, housed and furnished only with the essentials. If they desired luxuries, play equipment, special tools, private rooms, these could be earned by producing articles for use elsewhere in Pao, and almost all of the student’s spare time was devoted to small industrial ventures. They produced toys, pottery, simple electrical devices, aluminum ingots reduced from nearby ore, and even periodicals printed in Technicant. A group of eight-year students had joined in a more elaborate project: a plant to extract minerals from the ocean, and to this end spent all their funds for the necessary equipment.

The instructors were for the most part young Breakness dons. From the first, Beran was perplexed by a quality he was unable to locate, let alone identify; only after he had lived at Cloeopter two months did the source of the oddness come to him. It lay in the similarity which linked these Breakness dons. Once Beran had come this far, total enlightenment followed. These youths were all sons of Palafox. The name was never spoken in Beran’s hearing, and probably—so Beran conjectured—never out of it.

Surely they were aware of their common parentage. The situation was strange, provocative to the imagination. What could they gain on this alien planet? By all tradition they should be engrossed in their most intensive studies at the Institute, preparing themselves for the Authority, earning modifications. But no, here they worked at an occupation they must regard as menial. Beran found the entire situation mysterious.

His own duties were simple enough, and in terms of Paonese culture, highly rewarding. The director of the school, an appointee of Bustamonte’s, in theory, controlled the scope and policy of the school, but his responsibility was only nominal. Beran served as his interpreter, translating into Technicant such remarks that the director saw fit to make. For this service he was housed in a handsome cottage of cobbles and hand-hewn timber, a former farmhouse, paid a good salary and allowed a special uniform of gray-green with black and white trim.

A year passed. Beran took a melancholy interest in his work, and even found himself participating in the ambitions and plans of the students. He tried to compensate by describing with cautious enthusiasm the ideals of old Pao, but met blank unconcern. More interesting were the technical miracles they believed he must have witnessed in the Breakness laboratories.

During one of his holidays Beran made a dolorous pilgrimage to the old home of Gitan Netsko, a few miles inland. With some difficulty he found the old farm beside Mervan Pond. It was now deserted; the green glass windows were dusty and cracked, the timber dry, the fields of yarrow overgrown with thief-grass. He seated himself on a rotting bench under a low tree, and to his mind came sad images …

He climbed the slope of Blue Mountain, looked back over the valley. The solitude astonished him. Across all the horizon, over a fertile land once thronged with population, there was now no movement other than the flight of birds. Millions of human beings had been removed, most to other continents, but others had preferred to lie with their ancestral earth over them. And the flower of the land—the most beautiful and intelligent of the girls—had been transported to Breakness, to pay the debts of Bustamonte.

Beran despondently returned to Zelambre Bay. Theoretically it lay within his power to rectify the injustice—if he could find some means to regain his rightful authority. The difficulties seemed insuperable. He felt inept, incapable …

Driven by his dissatisfaction, he deliberately put himself in the way of danger, and journeyed north to Eiljanre. He took a room in the old Moravi Inn, on the Tidal Canal, directly opposite the walls of the Grand Palace. His hand hesitated over the register; he restrained the reckless impulse to scrawl Beran Panasper, and finally noted himself as Ercole Paraio.

The capital city seemed gay enough. Was it his imagination that detected an underlying echo of anger, uncertainty, hysteria? Perhaps not: the Paonese lived in the present, as the syntax of their language and the changeless rhythm of the Paonese day impelled them.

In a mood of cynical curiosity, he checked through the archives of the Muniment Library. Nine years back, he found the last mention of his name: “During the night the alien assassins poisoned the beloved young Medallion. Thus, tragically, the direct succession of the Panaspers ends, and the collateral line stemming from Panarch Bustamonte begins, with all auspices indicating tenure of extreme duration.”

Irresolute, unconvinced, without power to enforce any resolution or conviction he might have settled upon, Beran returned to the school on Zelambre Bay.

* * *

Another year passed by. The Technicants grew older, more numerous, and greatly more expert. Four small fabrication systems were established, producing tools, plastic sheet, industrial chemicals, meters and gauges; a dozen others were in prospect, and it seemed as if this particular phase of Bustamonte’s dream, at least, were to prove successful.

At the end of two years Beran was transferred to Pon, on Nonamand, the bleak island continent in the southern hemisphere. The transfer came as an unpleasant surprise, for Beran had established an easy routine at Zelambre Bay. Even more unsettling was the discovery that routine had become preferable to change. At the age of twenty-one, was he already enervated? Where were his hopes, his resolutions; had he so easily discarded them? Angry at himself, furious at Bustamonte, he rode the transport southeast across the rolling farmlands of South Vidamand, over the Plarth, across the orchards and vines of Minamand’s Qurai Peninsula, across that long peculiar bight known as The Serpent, over the green island Fraevarth with its innumerable white villages, and across the Great Sea of the South. The Cliffs of Nonamand rose ahead, passed below, fell behind; they flew into the barren heart of the continent. Never before had Beran visited Nonamand, and the wind-whipped moors covered with thunder-stones, black gorse, contorted cypress seemed completely un-Paonese.

Ahead loomed the Sgolaph Mountains, the highest of all Pao. And suddenly they were over ice-crusted crags of basalt, in a land of glaciers, barren valleys, rushing white rivers. The transport circled the shattered cusp of Mount Droghead, swung quickly down upon a bare plateau, and Beran had arrived at Pon.

The settlement was reminiscent in spirit, if not in appearance, of Breakness Institute. A number of dwellings spread haphazardly to the contour of the terrain, surrounding a central clot of more massive buildings. These, so Beran learned, comprised laboratories, classrooms, a library, dormitories, refectories and an administration building.

Almost immediately Beran conceived a vast dislike for the settlement. Cogitant, the language spoken by the Paonese indoctrinees, was a simplified Breakness, shorn of several quasi-conditional word-orders, and with considerably looser use of pronouns. Nonetheless the atmosphere of the settlement was pure Breakness, even to the costumes affected by the ‘dominies’—actually high-ranking dons. The countryside, while by no means as fierce as that of Breakness, was nevertheless forbidding. A dozen times Beran contemplated requesting a transfer, but each time restrained himself. He had no wish to call attention to himself, with the possibility of exposing his true identity.

Читать дальше