Palafox darted him a burning glance. To question the genetic strength of a Breakness dominie was a prime solecism. Bustamonte, aware of his mistake, added hastily, “However, I will agree to this figure. In return you must return me my beloved nephew, Beran, so that he may make preparation for a useful career.”

“As a visitor to the floor of the sea?”

“We must take account of realities,” murmured Bustamonte.

“I agree,” said Palafox in a flat voice. “They dictate that Beran Panasper, Panarch of Pao, complete his education on Breakness.”

Bustamonte broke out into furious protest; Palafox responded tartly; there was contention, with Bustamonte erupting into rage. Palafox remained contemptuously calm, and Bustamonte at last acceded to his terms.

The bargain was recorded upon film and the two parted, if not amicably, at least in common accord.

Winter on Breakness was a time of chill, of thin clouds flying down Wind River, of hail fine as sand hissing along the rock. The sun careened only briefly above the vast rock slab to the south, and for most of the day Breakness Institute was shrouded in murk.

Five times the dismal season came and passed, and Beran Panasper acquired a basic Breakness education.

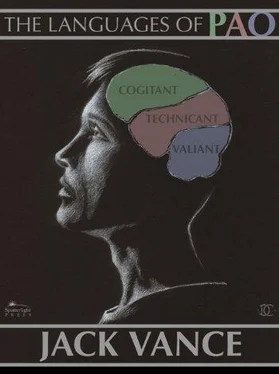

The first two years Beran lived in the house of Palafox, and much of his energy was given to learning the language. His natural preconceptions regarding the function of speech were useless, for the language of Breakness was different from Paonese in many significant respects. Paonese was of that type known as ‘polysynthetic’, with root words taking on prefixes, affixes and post-positions to extend their meaning. The language of Breakness was basically ‘isolative’, but unique in that it derived entirely from the speaker: that is to say, the speaker was the frame of reference upon which the syntax depended, a system which made for both logical elegance and simplicity. Since Self was the implicit basis of expression, the pronoun ‘I’ was unnecessary. Other personal pronouns were likewise non-existent, except for third person constructions—although these actually were contractions of noun phrases.

The language included no negativity; instead there were numerous polarities such as ‘go’ and ‘stay’. There was no passive voice—every verbal idea was self-contained: ‘to strike’, ‘to receive impact’. The language was rich in words for intellectual manipulation, but almost totally deficient in descriptives of various emotional states. Even if a Breakness dominie chose to break his solipsistic shell and reveal his mood, he would be forced to the use of clumsy circumlocution.

Such common Paonese concepts as ‘anger’, ‘joy’, ‘love’, ‘hate’, ‘grief’, were absent from the Breakness vocabulary. On the other hand, there were words to define a hundred different types of ratiocination, subtleties unknown to the Paonese—distinctions which baffled Beran so completely that at times his entire stasis, the solidity of his ego, seemed threatened. Week after week Fanchiel explained, illustrated, paraphrased; little by little Beran assimilated the unfamiliar mode of thought, and, simultaneously, the Breakness approach to existence.

Then … one day Palafox summoned him and remarked that Beran’s knowledge of the language was adequate for study at the Institute; that he would immediately be enrolled for the basic regimen.

Beran felt hollow and forlorn. The house of Palafox had provided a certain melancholy security; what would he find at the Institute?

Palafox dismissed him, and half an hour later Fanchiel escorted him to the great rock-melt quadrangle, saw him enrolled and installed in a cubicle at the student dormitory. He then departed, and Beran henceforth saw nothing either of Fanchiel or of Palafox.

So began a new phase of Beran’s existence on Breakness. All his previous education had been conducted by tutors; he had participated in none of the vast Paonese recitatives, wherein thousands of children chanted in unison all their learning—the youngest piping the numbers “Ai! Shrai! Vida! Mina! Nona! Drona! Hivan! Imple!”; the oldest the epic drones with which Paonese erudition concerned itself. For this reason Beran was not as puzzled by the customs of the Institute as he might have been.

Each youth was recognized as an individual, as singular and remote as a star in space. He lived by himself, shared no officially recognized phase of his existence with any other student. When spontaneous conversations occurred, the object was to bring an original viewpoint, or novel sidelight, to the discussion at hand. The more unorthodox the idea, the more certain that it would at once be attacked. He who presented it must then defend his idea to the limits of logic, but not beyond. If successful he gained prestige; if routed, he was accordingly diminished.

Another subject enjoyed a furtive currency among the students: the subject of age and death. The topic was more or less taboo—especially in the presence of a dominie—for no one died of disease or corporeal degeneration on Breakness. The dominies ranged the universe; a certain number met violent ends in spite of their built-in weapons and defenses. The greater number, however, passed their years on Breakness, unchanging except for perhaps a slight gauntness and angularity of the bone structure. And then, inexorably the dominie would approach his Emeritus status: he would become less precise, more emotional; egocentricity would begin to triumph over the essential social accommodations; there would be outbursts of petulance, wrath, and a final megalomania—and then the Emeritus would disappear.

Beran, shy and lacking fluency, at first held aloof from the discussions. As he acquired facility with the language, he began to join the discussions, and after a period of polemic trouncings, found himself capable of fair success. These experiences provided him the first glow of pleasure he had known on Breakness.

Interrelationships between the students were formal, neither amiable nor contentious. Of intense interest to the youth of Breakness was the subject of procreation in every possible ramification. Beran, conditioned to Paonese standards of modesty, was at first distressed, but familiarity robbed the topic of its sting. He found that prestige on Breakness was a function not only of intellectual achievement but also of the number of females in one’s dormitory, the number of sons which passed the acceptance tests, the degree of resemblance in physique and mind with the sire, and the sons’ own achievements. Certain of the dominies were highly respected in these regards, and ever more regularly was the name of Lord Palafox heard.

When Beran entered his fifteenth year, Palafox’s repute rivalled that of Lord Karollen Vampellte, High Dominie of the Institute. Beran was unable to restrain a sense of identification and so pride.

A year or two after puberty, a youth of the Institute might expect to be presented with a girl by his sire. In expectation of this occasion, the pubescent youths spent considerable time at the space terminal where they might inspect the broods of incoming women.

In solemn groups they stood to the side, making grave appraisals, speculating on the planet of origin of some particular individual, calling to mind the sexual customs of the particular planet, and occasionally, if language permitted, verifying their speculations by putting a series of searching questions.

Beran, attaining this particular stage in his development, was a youth of pleasant appearance, rather slender, almost frail. His hair was a dark brown, his eyes gray and wide, his expression pensive. Due to his exotic origin and a certain native diffidence, he was seldom party to what small group activity existed. When he finally felt the pre-adult stirrings in his blood and began to think of the girl whom he might expect to receive from Palafox, he went alone to the space terminal.

Читать дальше