Dharthi suddenly realized that if they were a new species, she would get to name them.

They were so immense, and dominated the light so completely, that very little grew under them. Some native fernmorphs, some mosses. Lichens shaggy on their enormous trunks and roots. Where one had fallen, a miniature Cytherean rain forest had sprung up in the admitted light, and here there was drumming, dripping rain, rain falling like strings of glass beads. It was a muddy little puddle of the real world in this otherwise alien quiet.

The trees stood like attentive gods, their faces so high above her she could not even hear the leaves rustle.

Dharthi forced herself to turn away from the trees, at last, and begin examining the structures. There were dozens of them – hundreds – sculpted out of the same translucent, mysterious, impervious material as all of the ruins in Aphrodite. But this was six, ten times the scale of any such ruin. Maybe vaster. She needed a team. She needed a mapping expedition. She needed a base camp much closer to this. She needed to give the site a name –

She needed to get back to work.

She remembered, then, to start documenting. The structures – she could not say, of course, which were habitations, which served other purposes – or even if the aboriginals had used the same sorts of divisions of usage that human beings did – were of a variety of sizes and heights. They were all designed as arcs or crescents, however – singly, in series, or in several cases as a sort of stepped spectacular with each lower, smaller level fitting inside the curve of a higher, larger one. Several had obvious access points, open to the air, and Dharthi reminded herself sternly that going inside unprepared was not just a bad idea because of risk to herself, but because she might disturb the evidence.

She clenched her good hand and stayed outside.

Her shell had been recording, of course – now she began to narrate, and to satlink the files home. No fanfare, just an upload. Data and more data – and the soothing knowledge that while she was hogging her allocated bandwidth to send, nobody could call her to ask questions, or congratulate, or –

Nobody except Kraken, with whom she was entangled for life.

“Hey,” her partner said in her head. “You found it.”

“I found it,” Dharthi said, pausing the narration but not the load. There was plenty of visual, olfactory, auditory, and kinesthetic data being sent even without her voice.

“How does it feel to be vindicated?”

She could hear the throb of Kraken’s pride in her mental voice. She tried not to let it make her feel patronized. Kraken did not mean to sound parental, proprietary. That was Dharthi’s own baggage.

“Vindicated?” She looked back over her shoulder. The valley was quiet and dark. A fumarole vented with a rushing hiss and a curve of wind brought the scent of sulfur to sting her eyes.

“Famous?”

“ Famous!? ”

“Hell, Terran-famous. The homeworld is going to hear about this in oh, about five minutes, given light lag – unless somebody who’s got an entangled partner back there shares sooner. You’ve just made the biggest Cytherean archaeological discovery in the past hundred days, love. And probably the next hundred. You are not going to have much of a challenge getting allocations now.”

“I –”

“You worked hard for it.”

“It feels like...” Dharthi picked at the bridge of her nose with a thumbnail.

The skin was peeling off in flakes: too much time in her shell was wreaking havoc with the natural oil balance of her skin. “It feels like I should be figuring out the next thing.”

“The next thing,” Kraken said. “How about coming home to me? Have you proven yourself to yourself yet?”

Dharthi shrugged. She felt like a petulant child. She knew she was acting like one. “How about to you?”

“ I never doubted you. You had nothing to prove to me. The self-sufficiency thing is your pathology, love, not mine. I love you as you are, not because I think I can make you perfect. I just wish you could see your strengths as well as you see your flaws – one second, bit of a squall up ahead – I’m back.”

“Are you on an airship?” Was she coming here?

“Just an airjeep.”

Relief and a stab of disappointment. You wouldn’t get from Aphrodite to Ishtar in an AJ.

Well , Dharthi thought. Looks like I might be walking home.

And when she got there? Well, she wasn’t quite ready to ask Kraken for help yet.

She would stay, she decided, two more sleeps. That would still give her time to get back to basecamp before nightfall, and it wasn’t as if her arm could get any more messed up between now and then. She was turning in a slow circle, contemplating where to sling her cocoon – the branches were really too high to be convenient – when the unmistakable low hum of an aircar broke the rustling silence of the enormous trees.

It dropped through the canopy, polished copper belly reflecting a lensed fisheye of forest, and settled down ten meters from Dharthi. Smiling, frowning, biting her lip, she went to meet it. The upper half was black hydrophobic polymer: she’d gotten a lift in one just like it at Ishtar basecamp before she set out.

The hatch opened. In the cramped space within, Kraken sat behind the control board. She half-rose, crouched under the low roof, came to the hatch, held out one her right hand, reaching down to Dharthi. Dharthi looked at Kraken’s hand, and Kraken sheepishly switched it for the other one. The left one, which Dharthi could take without strain.

“So I was going to take you to get your arm looked at,” Kraken said.

“You spent your allocations –”

Kraken shrugged. “Gonna send me away?”

“This time,” she said, “... no.”

Kraken wiggled her fingers.

Dharthi took it, stepped up into the GEV, realized how exhausted she was as she settled back in a chair and suddenly could not lift her head without the assistance of her shell. She wondered if she should have hugged Kraken. She realized that she was sad that Kraken hadn’t tried to hug her. But, well. The shell was sort of in the way.

Resuming her chair, Kraken fixed her eyes on the forward screen. “Hey. You did it.”

“Hey. I did.” She wished she felt it. Maybe she was too tired.

Maybe Kraken was right, and Dharthi should see about working on that.

Her eyes dragged shut. So heavy. The soft motion of the aircar lulled her. Its soundproofing had degraded, but even the noise wouldn’t be enough to keep her awake. Was this what safe felt like? “Something else.”

“I’m listening.”

“If you don’t mind, I was thinking of naming a tree after you.”

“That’s good,” Kraken said. “I was thinking of naming a kid after you.”

Dharthi grinned without opening her eyes. “We should use my Y chromosome. Color blindness on the X.”

“Ehn. Ys are half atrophied already. We’ll just use two Xs,” Kraken said decisively. “Maybe we’ll get a tetrachromat.”

THE MACHINE STARTS

Greg Bear

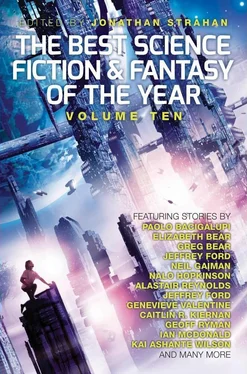

GREG BEAR(www.gregbear.com) is one of the most important science fiction writers of the past forty years. He is the multiple Hugo and Nebula awardwinning author of more than 35 novels, including Blood Music ; Eon and sequels Eternity and Legacy ; The Forge of God and sequel Anvil of Stars ; Queen of Angels and sequel /Slant ; Moving Mars ; Darwin’s Radio and sequel Darwin’s Children ; City at the End of Time , War Dogs and most recent novel, Killing Titan . Bear’s short fiction has won or been nominated for the Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards on multiple occasions, and has been collected in The Wind From a Burning Woman, Tangents, The Collected Stories of Greg Bear , and other volumes. His major stories include “Petra”, “Hardfought”, “Blood Music” and “Tangents”. His complete short fiction will be published in three volumes in 2016. Bear is the father of two young writers, Erik and Alexandra, and is married to Astrid Anderson Bear. The Bears make their home in Seattle.

Читать дальше