Finally, I called and he answered.

“I want to see you,” I said, when we had made our way through the pleasantries.

“Sunday?” Did his voice brighten, or was that just blind stupid hope?

Some trick of the noisy synthcoffee shop where I sat?

“No, Thede,” I said, measuring my words carefully. “I can’t. Can you do today?”

A suspicious pause. “Why can’t you do Sunday?”

“Something’s come up,” I said. “Please? Today?”

“Fine.”

The sea lion rookery. The smell of guano and the screak of gulls; the crying of children dragged away as the place shut down. The long night was almost upon us. Two male sea lions barked at each other, bouncing their chests together. Thede came a half hour late, and I had arrived a half hour early.

Watching him come my head swam, at how tall he stood and how gracefully he walked. I had done something good in this world, at least. I made him. I had that, no matter how he felt about me.

Something had shifted, now, in his face. Something was harder, older, stronger.

“Hey,” I said, bear-hugging him, and eventually he submitted. He hugged me back hesitantly, like a man might, and then hard, like a little boy. “What’s happening?” I asked. “What were you up to, last night?” Thede shrugged. “Stuff. With friends.”

I asked him questions. Again the sullen, bitter silence; again the terse and angry answers. Again the eyes darting around, constantly watching for whatever the next attack would be. Again the hating me, for coming here, for making him.

“I’m going away,” I said. “A job.”

“I figured,” he said.

“I wish I didn’t have to.”

“I’ll see you soon.”

I nodded. I couldn’t tell him it was a twelve-month gig. Not now. “Here,” I said, finally, pulling the package out from inside of my jacket.

“I got you something.”

“Thanks.” He grabbed it in both hands, began to tear it open. “Wait,” I said, thinking fast. “Okay? Open it after I leave.” Open it when the news that I’m leaving has set in, when you’re mad at me, for abandoning you. When you think I care only about my job .

“We’ll have a little time,” he said. “When you get back. Before I go away. I leave in eight months. The program is four years long.”

“Sure,” I said, shivering inside.

“Mom says she’ll pay for me to come home every year for the holiday, but she knows we can’t afford that.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. “‘Come home.’ I thought you were going to the Institute.”

“I am,” he said, sighing. “Do you even know what that means? The Institute’s design program is in Shanghai.”

“Oh,” I said. “Design. What kind of design?”

My son’s eyes rolled. “You’re missing the point, dad.”

I was. I always was.

A shout, from a pub across the Arm. A man’s shout, full of pain and anger.

Thede flinched. His hands made fists.

“What?” I asked, thinking, here, at last, was something “Nothing.”

“You can tell me. What’s going on?”

Thede frowned, then punched the metal railing so hard he yelped. He held up his hand to show me the blood.

“Hey, Thede –”

“Han,” he said. “My... my friend. He got jumped two nights ago. Soaked.”

“This city is horrible,” I whispered.

He made a baffled face. “What do you mean?”

“I mean... you know. This city. Everyone’s so full of anger and cruelty...”

“It’s not the city, dad. What does that even mean? Some sick person did this. Han was waiting for me, and mom wouldn’t let me out, and he got jumped. They took off all his clothes, before they rolled him into the water.

That’s some extra cruel shit right there. He could have died. He almost did.” I nodded, silently, a siren of panic rising inside. “You really care about this guy, don’t you?”

He looked at me. My son’s eyes were whole, intact, defiant, adult. Thede nodded.

He’s been getting bullied , his mother had told me. He’s in love . I turned away from him, before he could see the knowledge blossom in my eyes.

The shirt hadn’t been stolen. He’d given it away. To the boy he loved. I saw them holding hands, saw them tug at each other’s clothing in the same fumbling adolescent puppy-love moments I had shared with his mother, moments that were my only happy memories from being his age. And I saw his fear, of how his backwards father might react – a refugee from a fallen hate-filled people – if he knew what kind of man he was. I gagged on the unfairness of his assumptions about me, but how could he have known differently? What had I ever done, to show him the truth of how I felt about him? And hadn’t I proved him right? Hadn’t I acted exactly like the monster he believed me to be? I had never succeeded in proving to him what I was, or how I felt.

I had battered and broken his beloved. There was nothing I could say.

A smarter man would have asked for the present back, taken it away and locked it up. Burned it, maybe. But I couldn’t. I had spent his whole life trying to give him something worthy of how I felt about him, and here was the perfect gift at last.

“I love you, Thede,” I said, and hugged him.

“Daaaaad...” he said, eventually.

But I didn’t let go. Because when I did, he would leave. He would walk home through the cramped and frigid alleys of his home city, to the gift of knowing what his father truly was.

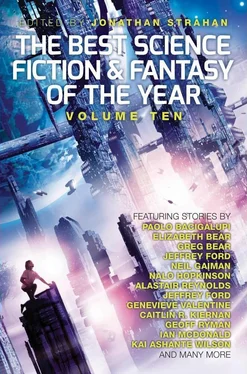

THE HEART’S FILTHY LESSON

Elizabeth Bear

ELIZABETH BEAR(matociquala.livejournal.com) was born on the same day as Frodo and Bilbo Baggins, but in a different year. When coupled with a childhood tendency to read the dictionary for fun, this led her inevitably to penury, intransigence, and the writing of speculative fiction. She is the Hugo, Sturgeon, Locus, and Campbell Award winning author of 26 novels and over a hundred short stories. Her dog lives in Massachusetts; her partner, writer Scott Lynch, lives in Wisconsin. She spends a lot of time on planes. Her most recent book is science fiction novel Karen Memory.

THE SUN BURNED through the clouds around noon on the long Cytherean day, and Dharthi happened to be awake and in a position to see it. She was alone in the highlands of Ishtar Terra on a research trip, five sleeps out from Butler base camp, and – despite the nagging desire to keep traveling – had decided to take a rest break for an hour or two. Noon at this latitude was close enough to the one hundredth solar dieiversary of her birth that she’d broken out her little hoard of shelf-stable cake to celebrate. The prehensile fingers and leaping legs of her bioreactor-printed, skin-bonded adaptshell made it simple enough to swarm up one of the tall, gracile pseudo-figs and creep along its gray smooth branches until the ceaseless Venusian rain dripped directly on her adaptshell’s slick-furred head.

It was safer in the treetops, if you were sitting still. Nothing big enough to want to eat her was likely to climb up this far. The grues didn’t come out until nightfall, but there were swamp-tigers, damnthings, and velociraptors to worry about. The forest was too thick for predators any bigger than that, but a swarm of scorpion-rats was no joke. And Venus had only been settled for three hundred days, and most of that devoted to Aphrodite Terra; there was still plenty of undiscovered monsters out here in the wilderness.

The water did not bother Dharthi, nor did the dip and sway of the branch in the wind. Her adaptshell was beautifully tailored to this terrain, and that fur shed water like the hydrophobic miracle of engineering that it was. The fur was a glossy, iridescent purple that qualified as black in most lights, to match the foliage that dripped rain like strings of glass beads from the multiple points of palmate leaves. Red-black, to make the most of the rainy grey light. They’d fold their leaves up tight and go dormant when night came.

Читать дальше