In the housing, I ease around the humming core of the generator and its whirring shaft. The dials are all still registering power – enough for my needs, at any rate. We’re still down to those last few replacement fuses, but there’s no need to swap one of them at the moment.

I climb the little ladder and poke my head out through the roof hatch. Steeling myself, pushing my fear aside, I put my elbows on the rim and lever my body up through the hatch. Finally I’m sitting on the rim, with my legs and feet still dangling back into the housing. The wind is hard and cold up here, a relentless solid force, but with the enclosing handrails there’s no real chance of me falling. All the same, it takes my last reserves of determination to rise from the hatch, pushing myself up until I am standing on the rubberised decking. The handrails seem too low now, and the gaps between the uprights too widely spaced. With each swoop of the blades, the housing moves under me. My knees wobble. My stomach flutters and sweat pools in the palms of my gloved hands.

But I will not fall. That’s not why I’ve come to the top of the turbine.

Once more I survey my little world from this lofty vantage. The hut, the instruments, the parked vehicle. The low sky. The boggy tracks of my daily routine.

The harder gleam of the causeway, arrowing away.

But it never gets anywhere. The causeway vanishes into bog and then the bog opens up into the silver mirror of a larger expanse of open water. I squint, trying to pick up the causeway’s continuation beyond the flooded area. There, maybe. A scratch of iron-grey, arrowing on toward the horizon. But dark shapes bordering that scratch. Cars, vans – all stopped. Some of them tipped over or emptied like skulls. Burnt out.

I might be imagining it.

Beyond the marsh, beyond the enclosing water, nothing that hints at civilisation.

I realise now that I’ve been here a lot longer than weeks. I know also that I don’t need to worry about being a scientist any more. That’s the least of anyone’s concerns. Being a scientist is just something I used to do, a long time ago.

I wish I could hold onto this. I wish I could remember that the paper doesn’t matter, that the journal doesn’t matter, that nothing matters. That the only thing left to worry about is holding on, keeping things at bay. But unless I’m mistaken that was the last of my medication.

Finally the wind and the swaying overcome my will. I start down the tower, back to the ground.

At the 4WD I stand and watch the birds. That clarity hasn’t completely left me, that knowledge of what I am and what has become of me. I can feel it slipping, draining out of my head as if there are holes in the base of my skull. For the moment, though, there’s still enough of it there. I know what happened.

But the murmuration still contains troubling structure – sharp edges, block knots of density, shifting domains and restless connections. Did I cause all of that to come into being, or is this now the way of things? Is it a kind of equivalence, order emerging in the natural world, while order is eclipsed in ours? Have I been trying to communicate with the murmuration, or is it the other way around? Which of us is the observer, which the phenomenon?

If I tried to kill it, will it find it in itself to forgive me?

I try to hold onto these questions. They seem hugely important to me now. But one pill was never going to hold the dusk at bay.

IN THE MORNING I feel much better about things. Finally, I think I can see a way through – a fresh approach, a new chance of publication. It will mean going back to the start of the process, but sometimes you have no choice – you just have to end things before they get any worse.

I draft a letter to the editor. Although it pains me to do it, I feel that we have no option but to request a new referee. Things have gone on long enough with this old one. Frankly the whole exchange was in danger of getting too personal. We all know that the anonymous part counts for very little these days, and in all honesty professional feelings were starting to get in the way. I had a suspicion about their identity, and of course mine was all to visible to them. We had history. Too much bad blood, too much accumulated recrimination and mistrust. At least this way we will be off to a clean start again.

I read it over, make a few alterations, then send the letter. It might be misplaced optimism, but this time I am quietly confident of success. I look forward to hearing from the editor.

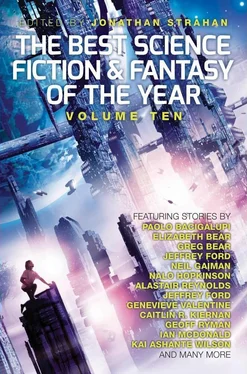

KAIJU MAXIMUS®: “SO VARIOUS, SO BEAUTIFUL, SO NEW”

Kai Ashante Wilson

KAI ASHANTE WILSONis the author of “The Devil in America”, which was nominated for the Nebula, World Fantasy, and Shirley Jackson Awards. His short fiction has been published by Tor.com and in the anthology Stories for Chip. His most recent work is short fantasy novel The Sorcerer of the Wildeeps , which is available from all fine booksellers. He lives in New York City.

IT HADN’T COME down since great-grandparent days, but as its last descent had left no stone on stone – nor man, woman, child alive – anywhere people had once dwelled aboveground on the continent, the hero would go up before it came down again, and kill the kaiju maximus . They would go too: the hero’s weakness, and her strength.

For long cool days, she led them up the old byways toward the spectre of the mountains. Finally they reached the foothills. Here and there leaves of the deep green forest had just begun turning red or gold in the last days of summer. He and the children were all fit, all well, and so most days the hero could get about twenty kiloms out of them. She carried the food, that pack twice the weight of his, which was plenty heavy enough. She brought down game for them if he asked, a turkey, or ducks. They did just as that old sciencer in the last cavestead had counseled: every morning a drop of her blood under the children’s tongues and his, and indeed the heroic factor served to ward them all from sickness. No more fevers, not a cough. The scaled dry patches on the boy’s neck and hands cleared up, and he suffered no more frightening episodes of breathlessness. In little more than a month the baby, looking all the time more and more like poor Sofiya, shot up several centimets, five or six, and put on as many kilos. And him? That ankle he’d twisted back in the spring stopped aching during the first and last hours of a long day’s hike, stopped aching at all. You don’t really know, until it’s gone, how much the pain was wearing on you all along.

Come downhill one bright chill afternoon, he and the baby and boy were resting in the swale, eating apples, when the hero came down from the sky. She gave him the choice of the last hill they’d climb that day. “Which one?” she said. Just north of them two hills overlapped in east-west adjacency. “Where’s the good water?”

He thought about it and said, “That one,” holding out his apple toward where, unseen and unheard, a freshwater spring bubbled up from cloven rock, and ran down down the chosen hill’s farside. Though much higher, the other hill looked easy-hiking. The hill awaiting them was squat, not half so high: but they’d end up climbing its height four or five times, after all the switchbacks, its sides being steep and densely forested, interrupted by brief sheer bluffs. There never really was a chance, was there, the easy hill might have had the water?

“Saw some ducks while I was up flying,” the hero said. (They only ever argued over the children – food for them, water for them, rest.) “But just those spoonies with orange fat.”

“That’s okay.”

“Kids won’t eat that kind, you said.” The hero’s latest eyes caught the light funny, as if prismatic oil were wetting them, not saltwater tears. “They taste too nasty.”

Читать дальше