Was that why I hadn’t returned home until Gramps’s death? Even then I knew there was more. Home was a morass where I would sink. I had tried one or two family holidays midway through college. They depressed me, my parents’ stagnation, their world where nothing changed. The trailer park, its tired residents, the dead-leaf-strewn grounds that always seemed to get muddy and wet and never clean. A strange lethargy would settle on me here, a leaden feeling that left me cold and shaken. Visiting home became an ordeal filled with guilt at my indifference. I was new to the cutthroat world of academia then and bouncing from one adjunct position to another was taking up all my time anyway.

I stopped going back. It was easier to call, make promises, talk about how bright my prospects were in the big cities. And with Gramps even phone talk was useless. He couldn’t hear me, and he wouldn’t put on those damn hearing aids.

So now I was living thousands of miles away with a girl Baba had never met.

I suppose I must’ve been hurt at his refusal of my help. The next few days were a blur between helping Mama with cleaning out Gramps’s room and keeping up with the assignments my undergrads were emailing me even though I was on leave. A trickle of relatives and friends came, but to my relief Baba took over the hosting duties and let me sort through the piles of journals and tomes Gramps had amassed.

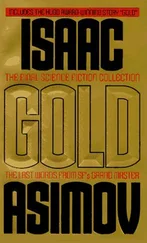

It was an impressive collection. Dozens of Sufi texts and religious treatises in different languages: Arabic, Urdu, Farsi, Punjabi, Turkish. Margins covered with Gramps’s neat handwriting. I didn’t remember seeing so many books in his room when I used to live here.

I asked Baba. He nodded.

“Gramps collected most of these after you left.” He smiled. “I suppose he missed you.”

I showed him the books. “Didn’t you say he was having memory trouble? I remember Mama being worried about him getting dementia last time I talked. How could he learn new languages?”

“I didn’t know he knew half these languages. Urdu and Punjabi he spoke and read fluently, but the others –” He shrugged.

Curious, I went through a few line notes. Thoughtful speculation on ontological and existential questions posed by the mystic texts. These were not the ramblings of a senile mind. Was Gramps’s forgetfulness mere aging? Or had he written most of these before he began losing his marbles?

“Well, he did have a few mini strokes,” Mama said when I asked. “Sometimes he’d forget where he was. Talk about Lahore, and oddly, Mansehra. It’s a small city in Northern Pakistan,” she added when I raised an eyebrow. “Perhaps he had friends there when he was young.”

I looked at the books, ran my finger along their spines. It would be fun, nostalgic, to go through them at leisure, read Rumi’s couplets and Hafiz’s Diwan . I resolved to take the books with me. Just rent a car and drive up north with my trunk rattling with a cardboard box full of Gramps’s manuscripts.

Then one drizzling morning I found a yellowed, dog-eared notebook under an old rug in his closet. Gramps’s journal.

BEFORE I LEFT Florida I went to Baba. He was crouched below the kitchen sink, twisting a long wrench back and forth between the pipes, grunting. I waited until he was done, looked him in the eye, and said, “Did Gramps ever mention a woman named Zeenat Begum?”

Baba tossed the wrench into the toolbox. “Isn’t that the woman in the fairy tale he used to tell? The pauper Mughal princess?”

“Yes.”

“Sure he mentioned her. About a million times.”

“But not as someone you might have known in real life?”

“No.”

Across the kitchen I watched the door of Gramps’s room. It was firmly closed. Within hung the portrait of the brown-eyed woman in the orange dopatta with her knowing half smile. She had gazed down at my family for decades, offering us that mysterious silver cup. There was a lump in my throat but I couldn’t tell if it was anger or sorrow.

Baba was watching me, his swollen fingers tapping at the corner of his mouth. “Are you all right?”

I smiled, feeling the artifice of it stretch my skin like a mask. “Have you ever been to Turkey?”

“Turkey?” He laughed. “Sure. Right after I won the lottery and took that magical tour in the Caribbean.”

I ignored the jest. “Does the phrase ‘Courtesan of the Mughals’ mean anything to you?”

He seemed startled. A smile of such beauty lit up his face that he looked ten years younger. “Ya Allah, I haven’t heard that in forty years. Where’d you read it?”

I shrugged.

“It’s Lahore. My city. That’s what they called it in those books I read as a kid. Because it went through so many royal hands.” He laughed, eyes gleaming with delight and mischief, and lowered his voice. “My friend Habib used to call it La-whore . The Mughal hooker. Now for Allah’s sake, don’t go telling your mother on me.” His gaze turned inward. “Habib. God, I haven’t thought of him in ages.”

“Baba.” I gripped the edge of the kitchen table. “Why don’t you ever go back to Pakistan?”

His smile disappeared. He turned around, slammed the lid of his toolbox, and hefted it up. “Don’t have time.”

“You spent your teenage years there, didn’t you? You obviously have some attachment to the city. Why didn’t you take us back for a visit?”

“What would we go back to? We have no family there. My old friends are probably dead.” He carried the toolbox out into the October sun, sweat gleaming on his forearms. He placed it in the back of his battered truck and climbed into the driver’s seat. “I’ll see you later.”

I looked at him turn the keys in the ignition with fingers that shook. He was off to hammer sparkling new shelves in other people’s garages, replace squirrel-rent screens on their lanais, plant magnolias and palms in their golfing communities, and I could say nothing. I thought I understood why he didn’t want to visit the town where he grew up.

I thought about Mansehra and Turkey. If Baba really didn’t know and Gramps had perfected the deception by concealing the truth within a lie, there was nothing I could do that wouldn’t change, and possibly wreck, my family.

All good stories leave questions , Gramps had said to me.

You bastard, I thought.

“Sure,” I said and watched my baba pull out and drive away, leaving a plumage of dust in his wake.

I CALLED SARA when I got home. “Can I see you?” I said as soon as she picked up. She smiled. I could hear her smile. “That bad, huh?”

“No, it was all right. I just really want to see you.”

“It’s one in the afternoon. I’m on campus.” She paused. In the background birds chittered along with students. Probably the courtyard. “You sure you’re okay?”

“Yes. Maybe.” I upended the cardboard box on the carpet. The tower of books stood tall and uneven like a dwarf tree. “Come soon as you can, okay?”

“Sure. Love you.”

“Love you too.”

We hung up. I went to the bathroom and washed my face. I rubbed my eyes and stared at my reflection. It bared its teeth.

“Shut up,” I whispered. “He was senile. Must have been completely insane. I don’t believe a word of it.”

But when Sara came that evening, her red hair streaming like fall leaves, her freckled cheeks dimpling when she saw me, I told her I believed, I really did. She sat and listened and stroked the back of my hand when it trembled as I lay in her lap and told her about Gramps and his journal.

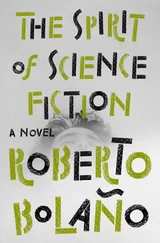

It was an assortment of sketches and scribbling. A talented hand had drawn pastures, mountaintops, a walled city shown as a semicircle with half a dozen doors and hundreds of people bustling within, a farmhouse, and rows of fig and orange trees. Some of these were miniatures: images drawn as scenes witnessed by an omniscient eye above the landscape. Others were more conventional. All had one feature in common: a man and woman present in the center of the scenery going about the mundanities of their lives.

Читать дальше