“Relax. Avoid emotion. Above all, keep away from women—Ruth, Maude, and the rest of them. That’s been the hardest job. It isn’t easy to break the habits of a lifetime.”

“I can well believe that,” replied Pearson, a little dryly. “How successful have you been so far?"

“Completely. You see, his own eagerness defeats his purpose, by filling me with a kind of nausea and self-loathing whenever I think of sex. Lord—to think that I’ve laughed at the prudes all my life, yet now I’ve become one myself!”

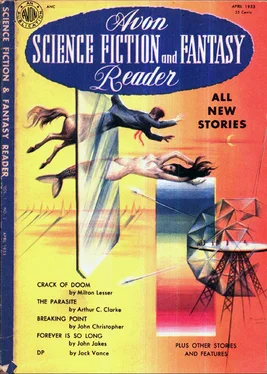

There, thought Pearson in a sudden flash of insight, was the answer. He would never have believed it, but Connolly’s past had finally caught up with him. Omega was nothing more than a symbol of conscience, a personification of guilt. When Connolly realized this, he would cease to be haunted. As for the remarkably detailed nature of the hallucination, that was yet another example of the tricks the human mind can play in its efforts to deceive itself. There must be some reason why the obsession had taken this form, but that was of minor importance.

Pearson explained this to Connolly at some length as they approached the village. The other listened so patiently that Pearson had an uncomfortable feeling that he was the one who was being humored, but he continued grimly to the end. When he had finished, Connolly gave a short, mirthless laugh.

“Your story’s as logical as mine—but neither of us can convince the other. If you’re right, then in time I may return to ‘normal.’ I can’t disprove the possibility; I simply don’t believe it. You can’t imagine how real Omega is to me. He’s more real than you are: if I close my eyes you're gone, but he’s still there, I wish I knew what he was waiting for! I’ve left my old life behind: he knows I won’t go back to it while he's there. So what’s he got to gain by hanging on?” He turned to Pearson with a feverish eagerness. “That’s what really frightens me, Jack. He must know what my future is—all my life must be like a book he can dip into where he pleases. So there must still be some experience ahead of me that he’s waiting to savor. Sometimes—sometimes I wonder if it’s my death.”

They were now among the houses at the outskirts of the village, and ahead of them the night-life of Syrene was getting into its stride. Now that they were no longer alone, there came a subtle change in Connolly’s attitude. On the hilltop he had been, if not his normal self, at least friendly and prepared to talk. But now the sight of the happy, carefree crowds ahead seemed to make him withdraw into himself; he lagged behind as Pearson advanced and presently refused to come any further.

“What’s the matter?” asked Pearson. “Surely you’ll come down to the hotel and have dinner with me?”

Connolly shook his head.

“I can’t,” he said. “I’d meet too many people.”

It was an astonishing remark from a man who had always delighted in crowds and parties: it showed, as nothing else had done, how much Connolly had changed. Before Pearson could think of a suitable reply, the other had turned on his heels and made off up a side street. Hurt and annoyed, Pearson started to pursue him, then decided that it was useless.

That night he sent a long telegram to Ruth, giving what reassurance he could. Then, tired out, he went to bed.

Yet for an hour he was unable to sleep. His body was exhausted, but his brain was still active. He lay watching the patch of moonlight move across the pattern on the wall, marking the passage of time as inexorably as it must still do in the distant age that Connolly had glimpsed. Of course, that was pure fantasy—yet against his will Pearson was growing to accept Omega as a real and living threat. And in a sense Omega was real—as real as those other mental abstractions, the Ego and the Subconscious Mind.

Pearson wondered if Connolly had been wise to come back to Syrene. In times of emotional crisis—there had been others, though none so important as this—Connolly’s reaction was always the same. He would return again to the lovely island where his charming, feckless parents had borne him and where he had spent his youth. He was seeking now, Pearson knew well enough, the contentment he had known only for one period of his life, and which he had sought so vainly in the arms of Ruth and all those others who had been unable to resist him.

Pearson was not attempting to criticize his unhappy friend. He never passed judgments; he merely observed with a bright-eyed, sympathetic interest that was hardly tolerance, since tolerance implied the relaxation of standards which he had never possessed. . . .

After a restless night, Pearson finally dropped into a sleep so sound that he awoke an hour later than usual. He had breakfast in his room, then went down to the reception desk to see if there was any reply from Ruth. Someone else had arrived in the night: two traveling cases, obviously English, were stacked in a corner of the hall, waiting for the porter to move them. Idly curious, Pearson glanced at the labels to see who his compatriot might be. Then he stiffened, looked hastily around, and hurried across to the receptionist.

“This Englishwoman,” he said anxiously. “When did she arrive?”

“An hour ago, Signor, on the morning boat.”

“Is she in now?”

The receptionist looked a little undecided, then capitulated gracefully.

“No, Signor. She was in a great hurry, and asked me where she could find Mr. Connolly. So I told her—I hope it was all right.”

Pearson cursed under his breath. It was an incredible stroke of bad luck, something he would never have dreamed of guarding against. Maude White was a woman of even greater determination than Connolly had hinted. Somehow she had discovered where he had fled, and pride or desire or both had driven her to follow. That she had come to this hotel was not surprising: it was an almost inevitable choice for English visitors to Syrene.

As he climbed the road to the villa, Pearson fought against an increasing sense of futility and uselessness. He had no idea what he should do when he met Connolly and Maude: he merely felt a vague yet urgent impulse to be helpful. If he could catch Maude before she reached the villa, he might be able to convince her that Connolly was a sick man and that her intervention could only do harm. Yet was this true? It was perfectly possible that a touching reconciliation had already taken place, and that neither party had the least desire to see him.

They were talking together on the beautifully laid-out lawn in front of the villa when Pearson turned through the gates and paused for breath. Connolly was resting on a wrought-iron seat beneath a palm-tree, while Maude was pacing up and down a few yards away. She was speaking swiftly; Pearson could not hear her words, but from the intonation of her voice she was obviously pleading with Connolly. It was an embarrassing situation: while Pearson was still wondering whether to go forward, Connolly looked up and caught sight of him. His face was a completely expressionless mask: it showed neither welcome nor resentment.

At the interruption, Maude spun round to see who the intruder was, and for the first time Pearson glimpsed her face. She was a beautiful woman, but despair and anger had so twisted her features that she looked like a figure from some Greek tragedy. She was suffering not only the bitterness of being scorned, but the agony of not knowing why.

Pearson’s arrival must have acted as a trigger to her pent-up emotions. She suddenly whirled away from him and turned towards Connolly, who continued to watch her with lacklustre eyes. For a moment Pearson could not see what she was doing: then he cried in horror: “Look out, Roy!”

Connolly moved with surprising speed, as if he had suddenly emerged from a trance. He caught Maude’s wrist, there was a brief struggle, and then he was backing away from her, looking with fascination at something in the palm of his hand. The woman stood motionless, paralyzed with fear and shame, knuckles pressed against her mouth.

Читать дальше