This was ridiculous, and I told him so.

‘Hear me out,’ he said. ‘Historical topless figures don’t peel themselves out of paintings, and you wandering naked about the Siddons in the small hours doesn’t seem very sensible, wouldn’t you agree?’

‘I’m not naked,’ I said, shivering.

‘If you’re not naked,’ he said slowly, ‘then how is it that I can see your doo-dads and your hoo-hah?’

‘You can’t.’

‘They’re as clear as the nose on my face.’

‘That’s a terrible use of an idiom.’

‘Agreed – but take a look for yourself.’

I looked down, and now that he mentioned it, I was naked – except for a single sock, one of Suzy’s, maroon in colour. I shivered again as the lights flickered back on, power returning, and the reality of the situation began to dawn.

‘Sod it,’ I said, ‘I’m narced, aren’t I?’

Lloyd nodded kindly. Hearing about narcosis is one thing, experiencing it quite another. Lloyd took my hand and led me back upstairs to my room, the full stupidity of my actions now becoming abundantly clear. Clytemnestra was exactly where she’d been all along, happily ensconced in the gilt frame, her immovable expression of murderous intent unchanged. My clothes, which I could have sworn I’d put on, were lying where I’d left them on the back of the chair.

‘I think I was dreaming,’ I said with a sigh.

‘Of blue Buicks and oak trees and hands and stuff?’

‘Actually, no.’

‘Then probably part of the narcosis. Have this hot chocolate; I’ll make another for myself.’

I told him I would be fine, but he insisted because I hadn’t yet put anything on room service. I agreed, and he wished me goodnight and departed.

Once I’d drunk the hot chocolate I settled back into bed, feeling unutterably foolish. Narcosis is something that you think will never happen to you, but when it does, it’s kind of scary – but only after the event. When it’s happening, it’s the best reality in town, with the possible exception of the dream in the Gower with Birgitta. I wanted to get back there if possible, so lay back, closed my eyes again and was soon fast asleep.

‘…The provenance of the Louvre Mona Lisa was finally established in the Spring of 1983, when margin notes written contemporaneously by Agostino Vespucci declared that “a fine painting of Lisa del Giocondo as she prepares to slumber is currently being [painted] by Leonardo”. Given that the Louvre Mona Lisa has her depicted as undeniably thin, the true da Vinci is now thought to be the Fat Lisa currently on display in Isleworth…’

–

Art and the Sleeping Artist , by Sir Troy Bongg

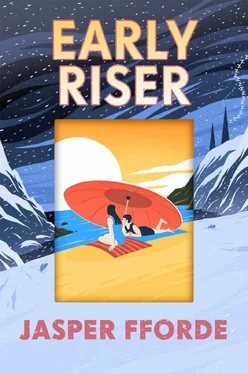

There was dreamless sleep, at first, and darkness. But not quite as I remembered the darkness, as simply shapeless, timeless ebony, but darkness as in an unlit hall – full of memories, and places, and peoples and things – the marker-stones of my life’s experience. Then a chasm, like a rent of linen, but both visual and aural, and in a second I was back: Birgitta, on the beach, blue-and-white towel, the bathing suit of fresh-leaf green and that orange-and-red parasol of spectacular size and splendour. The day was the same, the beach was the same, the Argentinian Queen was the same. I too was the same – not Charlie Worthing, but another, different, Charlie: Birgitta’s Charlie, sitting with her on the striped towel, wearing a black bathing suit and white pumps.

She looked at me and smiled, and I felt myself smile back. The dream was, as far as I could see, identical in every detail. The gulls cackled from on high, and the scent of the tide drifted in on the breeze. She gave me her captivating smile, and pushed the hair once more behind her ear. I was Charles, and she was Birgitta, and this was their perfect moment.

‘I love you, Charlie.’

‘I love you, Birgitta.’

The breakers boomed and then the child, with a gurgle of laughter, chased a beach ball toward shore’s edge. Again.

‘Is this really me?’ I asked, repeating myself before I’d realised it.

Birgitta blinked at me and smiled.

‘You’re Charlie now, my Charlie,’ she said with a giggle. ‘Try not to think about the facility and HiberTech Security. Just today and tomorrow, forty-eight hours. You and me. What Dreams May Come.’

‘What Dreams May Come,’ I replied.

Knowing that I might wake soon, I looked around, eager to soak in the fine detail.

Behind us was a path leading back up to the car park, where there would be a café of whitewashed clapboard that sold the best pistachio ice cream in the nation. We were close to where Birgitta’s mother lived, and would be staying in the room above the car house with its double brass bed, boxwood panelling and lace curtains. We’d leave early on Sunday and stop at Mumbles Pier to eat cockles and laver bread, while ‘Groove Me’ played on a wireless close by. I knew all these things without knowing how I knew, and odder still, I couldn’t just remember backwards, I could remember forwards . The beach was only a memory of better times, many years before. Following this, Birgitta and I had travelled separately to Sector Twelve. She’d painted and I’d worked at HiberTech as an orderly in the Sleep Sciences Division, Project Lazarus. We’d met rarely but passionately, and then we’d been parted, this time for good.

‘Happy snap?’ said a photographer who was plying his trade up and down the beach. ‘Proper tidy you’ll look and as reasonably priced as anywhere you’ll find.’

This was as far as I’d got in the dream the first time round and I expected to be awoken again, but I wasn’t. We agreed and he took the Polaroid, handed it to us and told us he would be back to pick up payment if it came out ‘to our proper satisfaction’. We watched the picture emerge, cementing the moment in time. It was the first time I got to see what I looked like. Birgitta’s Charles was ridiculously handsome, with fine features and dark curly hair that half obscured his eyes. Despite this, he looked somehow lost, hopeless and ultimately doomed—

—I was sitting at the base of an ancient oak, looking up. The spread of the tree went almost to the periphery of my vision, and the light of a fresh Summer’s morning filtered through the leaves. I blinked several times and sat up. The beach dream had abruptly cut out. Not with a fade or a segue but a tear . I was now in another place, another dream – one that I realised very quickly that Watson, Smalls, Moody, Birgitta and Lloyd had all visited before me.

I was sitting atop a rough stack of boulders that had been piled against the tree in a haphazard manner. The stones were large and of a bluish sandstone, smooth and flat and now an artificial island around the trunk. All about me the deep blue sky was punctuated by puffy clouds, and the surrounding grass stretched away in every direction to the horizon.

This felt, like the Birgitta dream that immediately preceded it, utterly real. Every detail was there about me – the texture in the bark, the veins in the leaves, the yellow bursts of lichen upon the rocks. The only evidence I had that this wasn’t real was that I knew it wasn’t. Nothing else. If that was so, then I could understand how Moody and Watson might have confused the two.

I looked at my hands. They still weren’t mine. But they weren’t Charles’ either.

They were old. A good seven decades, wrinkled, covered with liver spots and trembling. I felt weak, too, and the left side of my body had a sort of fuzzy dullness to it. Oddly, or perhaps not so oddly given his presence in all our lives, I was now dreaming I was Don Hector. His oldness, his dignity, his manner. But I wasn’t wholly him, I was partly him. Me, dreaming I was him, or him, dreaming he was me – I could only be sure I wasn’t Don Hector as he’d died two years before.

Читать дальше