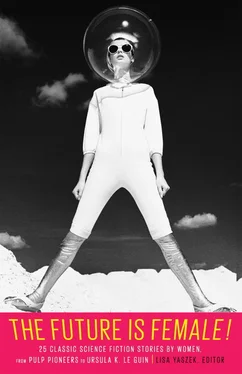

25 CLASSIC SCIENCE FICTION STORIES BY WOMEN,

FROM PULP PIONEERS TO URSULA K. LE GUIN

LISA YASZEK, EDITOR

INTRODUCTION

BY LISA YASZEK

STORIES speculating about the future of science, technology, and society began to appear across the globe over the course of the nineteenth century. But science fiction (SF) only came into its own in the American SF magazines of the early and mid-twentieth century. Tantalizing readers with sensational cover art and even more sensational titles like Amazing Stories , Fantastic Universe , and Astounding Science Fiction , dozens of new periodicals promised to reveal the shape of things to come. They offered not only action-packed adventure narratives but informed, even sometimes prescient, accounts of real-world scientific discovery and technological innovation. Along the way, they became laboratories for aesthetic exploration as well. Authors used these magazines to test the themes and techniques that would become associated with the genre, probing and expanding the limits of fiction; editors distilled the results of these experiments, commenting on shared histories and future trajectories for SF; and fans volunteered ideas and opinions about everything from scientific accuracy to the necessity of sex in speculative writing. This truly collaborative process, still ongoing, has established SF as the premier story form of technoscientific modernity.

As the title of this book asserts, SF was never just about boys and their toys. Instead, the future has always been female as well. This collection presents twenty-five stories written by three generations of American women between the launch of the first specialist genre magazines in the 1920s and the emergence of self-identified feminist SF in the 1970s. Adopting personae ranging from warrior queens and heroic astronauts to unhappy housewives and sensitive aliens, women were pioneers in developing our sense of wonder about the many different futures we might inhabit, partners in forging the creative practices associated with the best speculative fiction, and revolutionaries who blew up the genre when necessary to address the hopes and fears of American women.

So who were the women of early SF? The story of women in this field has long been celebrated by fans, who do the important cultural work of preserving genre history amongst themselves, and, more recently, by authors and scholars who share this history with others outside the SF community. However, such efforts are often overshadowed by “commonsense” assumptions about the historic relations of gender and genre. These assumptions have all but taken on the status of myth and posit that: (1) Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein is a foundational SF text, but few other women participated in the genre until the advent of feminist SF; (2) women sometimes wrote SF before the 1970s but had to disguise themselves as men to get published in a community that was inherently hostile to their sex; and (3) even when early women SF authors did write under their own names, they followed the lead of their male counterparts, celebrating science and technology in ways that reinforced rather than transformed our understanding of science and society.

These myths remind us of what we value in the present moment, and enjoy in increasing abundance: women who write scientifically responsible and socially daring fiction that encourages us to see our own world and its many possible futures in startling new ways. But they also beg an important question. Where did all these modern wonder women—writers like C. J. Cherryh, N. K. Jemisin, Ann Leckie, Nnedi Okorafor, Jo Walton, and Martha Wells, to name just some—come from in the first place?

As it turns out, women have been involved in shaping SF all along. Between the mid-1920s and the late 1960s, nearly 300 women published in the principal genre-specialist magazines—about 15 percent of all contributors, just going by the numbers. {1} 1 See Pamela Sargent, “Women in Science Fiction,” in Women of Wonder (New York: Vintage, 1975), and Eric Leif Davin, Partners in Wonder: Women and the Birth of Science Fiction, 1926–1965 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2006).

Most were fiction writers but some also helped to develop their chosen genre as editors, critics, poets, artists, and science journalists. Still others made their mark in the harder-to-quantify and still-understudied realm of fandom: publishing zines, sharing fan fiction, exerting significant influence on SF as its keenest audience. Women were active within professional organizations (helping to found the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, the Fantasy Amateur Press Association, and the Milford and Clarion Writers’ Workshops), and won every award and honor the community had to confer (see the Biographical Notes to this volume for individual Hugos, Nebulas, and other distinctions).

While it is true that women in SF occasionally met resistance from male writers, editors, and fans who disliked their presence in the field, most recall such incidents as isolated ones. From the start, SF magazine editors appear to have encouraged women’s contributions—as Leigh Brackett put it, “editors aren’t buying sex, they’re buying stories.” {2} 2 Paul Walker, “Leigh Brackett: Interview,” Speaking of Science Fiction (Oradell, NJ: Luna Publications, 1978), 371–83.

At Amazing Stories , the pioneering Hugo Gernsback “liked the idea of a woman invading the field he had opened,” as Leslie F. Stone remembered. {3} 3 In a 1974 speech to the Baltimore Science Fiction Society, published as “Day of the Pulps,” Fantasy Commentator 9.50 (Fall 1997): 100–101.

C. L. Moore “never felt the least bit downed because I was a woman”—indeed Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright is reported to have closed his office for the day in celebration when he received Moore’s now-famous story “Shambleau.” {4} 4 Jeffrey M. Elliot, “C. L. Moore: Poet of Far-Distant Futures,” Pulp Voices; or, Science Fiction Voices #6: Interviews with Pulp Writers and Editors (San Bernardino, CA: Borgo Press, 1983), 45–51.

For Zenna Henderson, Anthony J. Boucher and Francis J. McComas of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction seemed like “midwives” to her career. {5} 5 Zenna Henderson, “The People Series,” in Joseph Olander, Martin Harry Greenberg, and Frederik Pohl, eds., The Great Science Fiction Series (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 173–74.

And so the question remains: if women were a small but generally welcome part of the early SF world, why did so many adopt androgynous or male pseudonyms? The short answer is that most didn’t—and those who did had good reasons for their deception that had little to do with their SF careers. Almost all of the twenty-six authors featured in this anthology published primarily under their own, clearly feminine names, or under female pseudonyms; others (Leslie F. Stone, Leigh Brackett, Marion Zimmer Bradley) were given androgynous names at birth but published as women. (Throughout this volume, we’ve used each story’s original byline; real names are provided in the Biographical Notes.) In the few well-known cases where women deliberately concealed their true identities, they did so for complex professional reasons. Catherine Lucille Moore became “C. L.” so as not to jeopardize her banking job during the Great Depression. Alice Mary Norton reinvented herself as Andre Norton (also writing occasionally as Allen Weston or Andrew North) when she first launched a career writing boys’ adventure tales. Alice Sheldon, spotting a jar of Tiptree marmalade on a supermarket shelf, came up with the pseudonym James Tiptree, Jr., to protect her identity as a former CIA agent and budding experimental psychologist. As each of these examples suggests, the problem was not the reception of women in SF per se, but patterns of sexual discrimination across American culture. Pseudonymous authorship was common practice for male SF writers as well, and is one of the genre’s fascinating quirks; a couple of the apparently female authors we considered for the present volume turned out in fact to be men.

Читать дальше