Nancy Kress

TERRAN TOMORROW

The major advances in civilization are processes that all but wreck the societies in which they occur…. It is the business of the future to be dangerous; and it is among the merits of science that it equips the future for its duties.

—Alfred North Whitehead

The brain is wider than the sky

For, put them side by side

The one the other will contain

With ease, and you beside.

—Emily Dickinson

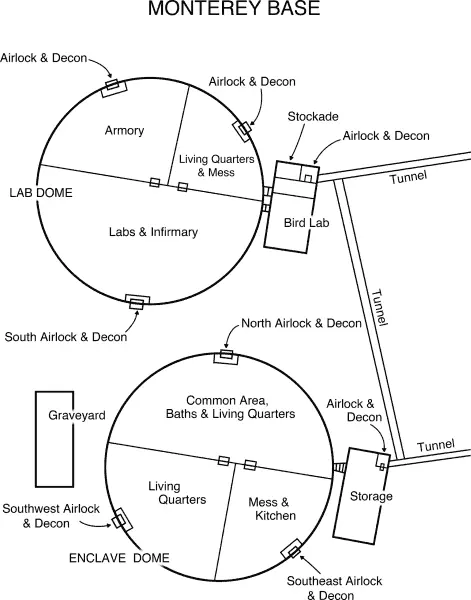

Jason stood in a small enclosure between two doors, leaned forward, and touched the tip of his finger to the pad mounted on the door in front of him. The door said, “Retinal scan and digital chip match. Colonel Jason Jenner,” opened to a long flight of metal steps, and locked behind him. His boots rang on each step.

At the bottom was a small windowless space with three doors. Two were unmarked, one of heavy wood and one of alien metal. The third, fitted with a decontamination chamber and the soft whoosh of negative pressure, bore a sign:

BIOHAZARDOUS MATERIAL

DANGER!

AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY

Jason keyed his way into the unmarked wooden door and closed it. In a tiny, sound-baffled space, a soldier jumped up from a stool and saluted.

Jason said, “Any trouble, Corporal?”

“No, sir. Sleeping, breathing, saying nothing.”

The guard room led to two cells, both with a single barred plastic window. Jason opened one of the cell doors and entered. The cell stank. The prisoner, naked, lay on his side on the bare floor in a stain of his own dried piss. His wrists were manacled with a short chain; another secured one ankle to the wall. Both had bloodied strips of skin. He opened his eyes to stare at Jason, who had to restrain himself from kicking him.

This was one of the men who had broken the world.

“Dr. Anderson, are you ready to talk to me?”

The prisoner said nothing. He had water within reach but had not eaten for three days. Only a few of the people in the base above, none of them civilians, even knew he was here. It had taken Army Intelligence—such as it was, since the Collapse—eight years to find this man. He was the last Gaiist they would ever find.

“If you don’t talk to me…”

Jason didn’t have to finish the sentence, which was good. He was weak enough—that’s how he thought of it—to shrink from torture, even though this man deserved anything that Jason’s men could do to him. But the sentence was such a cliché, even if the situation was not. Never before in the world had there been a situation like this. But always somewhere in Jason’s mind, inescapable as the dull throb of headache, was what Colin would think.

The prisoner finally spoke. “We saved the Earth.”

Anger surged so strong that for a moment Jason’s vision filled with red haze. He regained control.

“Are you going to tell us their plans? New America is your enemy as much as ours.”

Anderson went on gazing at him from pale blue eyes. For a moment Jason thought that Anderson was actually going to give up. But all he did was repeat, “We saved the Earth.”

Disgusted, Jason turned to leave. To Anderson he said, “You have until tomorrow morning to talk voluntarily.” To the sergeant, “No change in treatment.”

“Yes, sir.”

We saved the Earth.

Nothing could be less true.

Or more so.

Her name was Jane.

She told this to all nine people aboard the spaceship Return , her own people first. Her father, reading in a corner of a big room that ten people could not fill, looked at her calmly. “Yes, Jeg^faan, if you prefer. ‘Jane.’” He did not ask why the change. He knew. When you go to live on another planet, you must adapt. Worlders had always, of necessity, been good at adaptation. It was in their genes. And now adaptation was Jane’s mission: she would be the translator, the bridge between worlds.

Glamet^vor¡, with whom Jane once thought she might sign a mating contract, frowned. “I will keep my identity on Terra, and that includes my name. I am Glamet^vor¡,” he said, emphasizing the rising inflection in the middle and the click at the end, the way children did. In many ways, Jane thought, he was a child, although the most brilliant biologist on World, after her father.

“As you wish,” she said mildly. It was good that she had changed her mind about the mating contract. “Changed her mind”—that was a Terran expression, as if a mind was something that could be removed and replaced like a body wrap. English words came more easily to her now, after constant study for so long, but the meanings revealed by the words still astonished her.

She found Glamet^vor¡’s sister with their brother in a sleeping cabin. La^vor, the same age as Jane, was devoted to the boy, who could not speak more than a few words. Something had gone wrong at Belok^’s birth; his mother had died and Belok^’s brain had been damaged. Not, of course, that that made any difference to his siblings’ decision to bring him to Terra. They were lahk.

“La^vor,” Jane said, “I will be called ‘Jane’ now.”

“Why?”

“It’s a Terran name.”

La^vor, nowhere near as intelligent as her older brother, frowned. “You are not Terran.”

“No. But here, I will be called Jane.”

“All right,” La^vor said. She was never argumentative.

Belok^ laughed, but not because he understood. He often laughed or cried inappropriately, following vague ideas in his vague brain. Jane smiled and touched his arm. Like all Worlders, Belok^ had coppery skin, plus the huge dark eyes that had evolved on World to better gather Skihlla’s orangey light. As tall as most Worlders even though he hadn’t finished growing, Belok^ was much wider. If he had been as prickly as Glamet^vor¡, his baby mind in an almost-man’s body might have been difficult to lead, but Belok^ had the same sweet, accommodating disposition as his sister.

None of the Terrans, Jane suspected, fully understood why Belok^ had been brought with them. Terrans did not understand the unbreakable bonds of a lahk. Not even Marianne Jenner, whom Jane sought out next. Marianne sat on the bridge with Dr. Patel and Branch Carter.

Jane said in English, “My name here will be Jane, please. And I will call you Dr. Jenner now, not Marianne-kal, if that is all right.”

“Just call me Marianne,” the older woman said. Jane looked at her more closely. Marianne-kal… no, Dr. Jenner… no, Marianne looked sad. That was to be expected, perhaps. She had left behind her son Noah, married to a Worlder, and her granddaughter. She had two more children on Terra, but when she arrived there, twenty-eight years would have passed since her departure. Marianne’s daughter would be a Terran-year older than Marianne. Jane could not imagine how that would be.

“I feel your sadness,” she said, and Marianne looked at her sharply, started to say something, and then did not.

Dr. Patel said quickly, “‘Jane’—pretty name. Call me Claire.”

Читать дальше