“Leroy. You got to jump. You got to jump now.”

He climbed out onto the hull, hooking one hand on the door frame so he could coil his feet under him, push his legs down as far as they’d go. The bone-grey moon started to swell, and he opened his hand.

For a moment, he crouched. Then he jumped, hard and straight and true. He closed his eyes, screwed them tight shut, because he was terrified. He’d rather not know that Phobos would hit him with all the casual effort of swatting a moth.

There was nothing. And nothing. And nothing.

“You did it,” shouted a jubilant voice in his helmet, “You made it, Leroy. God speed, you glorious man. Say hello to the a–”

He opened one eye. Mars. Big and red. He opened the other. To his right, Phobos ground on in its orbit, chemical fire stuttering to an end on its planetward limb. Dust twinkled in its path, and patted softly on Johnson’s space suit. As the moon receded, even that lessened, and he was left alone, face down over Elysium.

The two second tick had gone. And with it, Bradbury.

His own breathing. The pulse in his ears. The hum of fans and the hiss of air. That was going to be it from now on, until those failed and fell silent. Some time later, his orbit would decay, and he’d fall, a fiery Icarus to the land below. Parts of him would reach the surface, and the bacteria within him would spill out onto an alien and inhospitable environment, in turn to wither and die.

Or perhaps not.

A spark of light flashed at the edge of the ice cap, and rose towards him on a pillar of ragged smoke that dragged through the clear, pink Martian sky.

We saw a ship emerging from near the point of flare. It grew steadily larger, catching flecks of sunlight, like the carapace of a golden insect.

_________

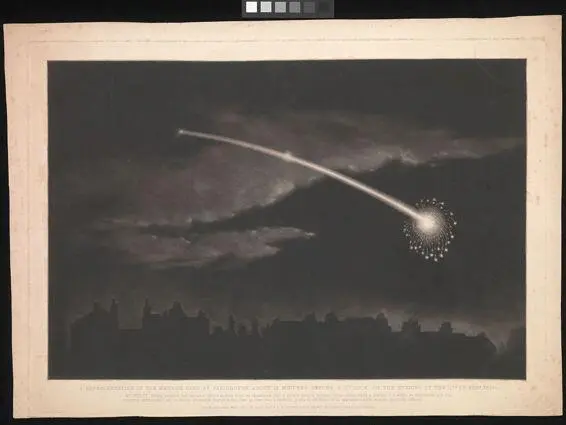

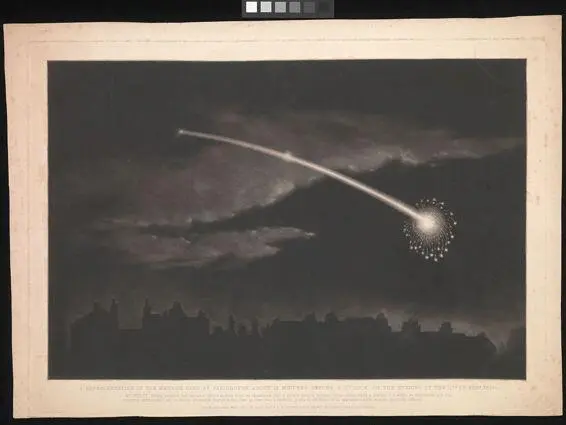

A mezzotint representation of a bright exploding meteor, seen over London on the evening of 1850. The original drawing was Matthew Cotes Wyatt. Wyatt also produced the engraving so that “a faithfully graphic exhibition of its appearance might be more generally diffused”. (1850)

SAGA’S CHILDREN

E. J. SWIFT

You will have heard of our mother, the astronaut Saga Wärmedal. She is famous, and she is infamous. Her face, instantly recognizable, appears against lists of extraordinary feats, firsts and lasts and onlys. There are the pronounced cheekbones, the long jaw, that pale hair cropped close to the head. In formal portraits she looks enigmatic, but in images caught unaware◦– perhaps at some function, talking to the Administrator of the CSSA or the Moon Colony Premier; in situations, in fact, where we might imagine she would feel out of place◦– she is animated, smiling. In those pictures, it is possible to glimpse the feted adventurer who traversed the asteroid belt without navigational aid.

We knew her only once, on Ceres.

You will have heard of what happened on Ceres.

Ours is one of many versions of Saga’s story. Widely distributed are a number of official biographies, and you can easily find another few dozen from less reputable sources. She is the subject of documentaries and immersion, avatars and educational curricula. We were not consulted in their production. But then, we did not know her; we only knew her contradictions, of which there were many. One small but significant example: she renounced her European passport in order to gain Chinese citizenship, yet she gave each of us a traditionally Scandinavian name.

We can say for certain that Saga was born in Ümea, Sweden, where in winter the darkness lies low and thick and heavy and the snow crunches underfoot with that particular sound heard only on Earth. Ulla, the oldest of us, remembers Ümea snow. She remembers the flakes falling on her head and the cold tingling sensation as they melted through her hair into her scalp. At least, this is what she says, and so we agree that this is how it was.

We know that Saga grew up in Ümea with a single mother. The biographies depict her as an exceptionally clever child, excelling in the fields of science and mathematics. A solitary creature. Decisive. Sure. In some editions, Saga herself is quoted:

It was when I saw the lights for the first time, the Aurora Borealis. The most beautiful thing on Earth. But it wasn’t on Earth. That’s when I knew what I wanted to be.

So she did what every child who wishes to be an astronaut must do. Saga taught herself Mandarin.

By age sixteen she was fluent. She applied to the most prestigious university in Beijing to study astro-engineering, and graduated with the top marks in her year. She was promptly accepted as a trainee astronaut in the Chinese Solar System Administration, a move almost unheard of for Europeans, and especially at such a young age. From there her career took off in meteoric fashion. News of her escapades was celebrated across worlds. She mapped the Martian planet. She led the first missions to Jupiter’s moons.

The biographies are less interested in Saga’s domestic life, if we can refer to it as such, and even between us we are not entirely settled on the details. We were raised by our fathers and grandmother. We knew Saga only through occasional communications from the outer planets, and nothing of one another’s existence. She sent us the debris of space. In our bedrooms we stored asteroid crystals and jars of red dust from Mars. We dreamed of Saga sailing through the stars, tailed by comets.

In her transmissions, she would tell each of us the same thing.

She loved us.

We must work hard.

Seek wisely.

Dream deeply.

Her hologram, flickering gently the way we imagined ghosts might, would flood us with bewilderment. We wanted to touch her, but when we put our fingertips to hers, there was nothing but air.

Since we found one another, we have spent many hours puzzling over the mystery of our existence. We do not mean this in an existential manner, although of course we ask those questions as much as the next human being. The mystery we share is something more personal. We would like to know why Saga chose to create us at all.

Ulla’s conception must have been an accident◦– still early in her career, it was not a good time for Saga to have a child, and an abortion would have been more practical. Ulla was born in Ümea (or says she was, as she says she remembers snow. But her father brought her up in Beijing, where, we imagine, he lived out his life awaiting Saga’s return. He waited a long time) but the greater question is why she was born at all. Could Saga have been unaware of her predicament until it was too late? How had she failed to take precautions?

Five years later, Per appeared on the Moon colony. He may have been intended, although a relationship with his father was not. (Nonetheless Per’s father did his best until Per reached sixteen, upon which date his father moved to Mars, we imagine, to search for Saga. He searched a long time.) Per grew up among space farers. Pilgrims, adventurers, criminals on the run, ambassadors, colonists and writers: all passed through Moon and recounted their tales whilst Per, in his first paid job, served them cups of mulled moonshine.

None of us are astronauts, but we have travelled. It is true that much of our journeying was done before we were born. Ulla went to the Moon and back, the size of a fingernail. Per went as far as Mars, and felt its heavy gravity pulling him down against the lining of Saga’s womb. Signy, we believe, was conceived on a ship orbiting Europa under Jupiter’s yellow gaze, and later returned to Earth and entrusted to the care of Saga’s mother in Sweden. Signy is the only one of us to have known our grandmother.

Читать дальше