“At least she doesn’t want copies of Marco and Polo,” says Ana.

“Yeah, thank goodness for that,” agrees Derek. A spouse can almost always make a copy of a digient, and when a divorce isn’t amicable, it’s all too easy to use one to get back at one’s ex. They’ve seen it happen on the forums many times.

“Enough of that,” says Derek. “Let’s talk about something else. What’s happening with you?”

“Nothing, really.”

“You looked like you were in a good mood until I started talking about Wendy.”

“Well, yeah, I was,” she admits.

“So is there something in particular that’s got you feeling so upbeat?”

“It’s nothing.”

“Nothing’s got you in a good mood?”

“Well, I have some news, but we don’t have to talk about it now.”

“No, don’t be silly, it’s fine. If you’ve got good news, let’s hear it.”

Ana pauses and then, almost apologetically, says, “Kyle and I have decided to move in together.”

Derek is stunned. “Congratulations,” he says.

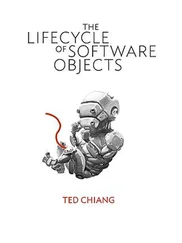

Two more years pass. Life goes on.

Occasionally Ana, Derek, and the other education-minded owners have their digients take some standardized tests, to see how they compare with human children. The results vary. The Fabergé digients, being illiterate, can’t take written tests, but they seem to be developing well according to other metrics. Among the Origami digients, there’s a curious split in the test results, with half continuing to develop over time and half hitting a plateau, possibly due to a quirk in the genome. The Neuroblast digients do reasonably well if they’re permitted the same allowances in testing that dyslexic humans are given; while there’s variation between the individual digients, as a group their intellectual development continues apace.

What’s harder to gauge is their social development, but one encouraging sign is that the digients are socializing with human adolescents in various online communities. Jax becomes interested in tetrabrake, a subculture focused on virtual dance choreography for four-armed avatars; Marco and Polo have each joined a fan club for a serial game drama, and each regularly tries to convince the other of the superiority of his choice. Even though Ana and Derek don’t really understand the appeal of these communities, they like the fact that their digients have become part of them. The adolescents who dominate these communities seem unconcerned with the fact that the digients aren’t human, treating them as just another kind of online friend they are unlikely to meet in person.

Ana’s relationship with Kyle has its ups and downs, but is generally good. They occasionally go out with Derek and whomever he’s dating; Derek sees a series of women, but nothing ever becomes serious. He tells Ana that it’s because the women he dates don’t share his interest in digients, but the truth is that his feelings for Ana refuse to go away.

The economy goes into a recession after the latest flu pandemic, prompting changes in the virtual worlds. Daesan Digital, the company that created the Data Earth platform, makes a joint announcement with Viswa Media, creator of the Real Space platform: Data Earth is becoming part of Real Space. All Data Earth continents will be replaced by identical Real Space versions added to the Real Space universe. They’re calling it a merger of two worlds, but it’s just a polite way of saying that, after years of upgrades and new versions, Daesan can no longer afford to keep fighting the platform wars.

For most customers, all this means is that they can travel between more virtual locations without logging out and in again. Over the last few years, almost all of the companies whose software runs on Data Earth have created versions that run on Real Space. Gamers who play Siege of Heaven or Elderthorn can simply run a conversion utility, and their inventories of weapons and clothing will be waiting for them on the Real Space versions of the game continents.

One exception, though, is Neuroblast. There isn’t a Real Space version of the Neuroblast engine—Blue Gamma folded before the platform was introduced—which means that there’s no way for a digient with a Neuroblast genome to enter the Real Space environment. Origami and Fabergé digients experience the migration to Real Space as an expansion of possibilities, but for Jax and the other Neuroblast digients, Daesan’s announcement essentially means the end of the world.

· · ·

Ana is getting ready for bed when she hears the crash. She hurries out to the living room to investigate.

Jax is wearing the robot body, examining his wrist. One of the tiles on the wall display next to him is cracked. He sees Ana enter and says, “I sorry.”

“What were you doing?” she asks.

“I very sorry.”

“Tell me what you were doing.”

Reluctantly, Jax says, “Cartwheel.”

“And your wrist gave way and you hit the wall.” Ana takes a look at the robot body’s wrist. As she feared, it will require replacement. “I don’t make these rules because I don’t want you to have fun. But this is what happens when you try dancing in the robot body.”

“I know you said. But I try little dancing, and body fine. I try little more, and body still fine.”

“So you tried a little more, and now we have to buy a new wrist, and a new display tile.” She briefly wonders how quickly she can replace them, if she can keep Kyle—who is out of town on business—from finding out about this. A few months ago Jax damaged a piece of sculpture that Kyle loved, and it might be better not to remind him of that incident.

“I very very sorry,” says Jax.

“Okay, back to Data Earth.” Ana points to the charging platform.

“I admit was mistake—”

“Just go.”

Jax dutifully heads over. Just before he steps on the platform, he says quietly, “It not Data Earth.” Then the robot body’s helmet goes dark.

Jax is complaining about the private version of Data Earth that the Neuroblast user group has set up, duplicating many of the continents from the original. In one respect it’s much better than the private island they used as a refuge from the IFF hack, because now processing power is so cheap that they can run dozens of continents. In another respect it’s much worse, because those continents are almost entirely devoid of inhabitants.

The problem is not just that all the humans have moved to Real Space. The Origami and Fabergé digients have gone to Real Space, too, and Ana can hardly blame their owners; she’d have done the same, given the opportunity. Even more distressing is that most of the Neuroblast digients are gone as well, including many of Jax’s friends. Some members of the user group quit when Data Earth closed; others took a wait-and-see approach but grew discouraged after they saw how impoverished the private Data Earth was, choosing to suspend their digients rather than raise them in a ghost town. And more than anything else, that’s what the private Data Earth resembles: a ghost town the size of a planet. There are vast expanses of minutely detailed terrain to wander around in, but no one to talk to except for the tutors who come in to give lessons. There are dungeons without quests, malls without businesses, stadiums without sporting events; it’s the digital equivalent of a postapocalyptic landscape.

Jax’s human friends from the tetrabrake scene used to log in to the private Data Earth just to visit Jax, but their visits have grown increasingly infrequent; all the tetrabrake events happen on Real Space now. Jax can send and receive choreography recordings, but a major part of the scene is live gatherings where choreography is improvised, and there’s no way for him to participate in those. Jax is losing most of his social life in the virtual world, and he can’t find one in the real one: his robot body is categorized as an unpiloted free-roaming vehicle, so he’s restricted from public spaces unless Ana or Kyle is there to accompany him. Confined to their apartment, he becomes bored and restless.

Читать дальше