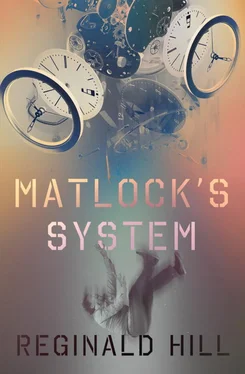

Matlock was sitting in the grass looking out towards the cityscape and wondering what was going on in the world of men and action he seemed to have left behind. Suddenly impatient for activity he jumped to his feet and without a word to Phillip set off across the stones. As he trod on the first one a hooded monk started across from the other side. When he saw Matlock he stopped sharply and stared right at him. The sun was striking athwart his hood and only the barest hint of features could be made out in the dark shadows beneath.

Then he stepped back to the bank. At first Matlock took this to be merely an act of courtesy but as he continued over the stones, he saw the monk, pulling his cowl still further over his head, set off briskly along the path beside the river.

Matlock stood in the middle of the river and watched him go. He heard Phillip come up behind him.

“He didn’t want to meet one of us,” Matlock said.

“Surely not. A change of plan. Something remembered which took him back that way. That was all.”

“If you say so.”

But Matlock was beset by a strange sense of familiarity as he watched the now distant figure.

“Tell me, Phillip,” he said, “are there two types of monk here? Or degrees or ranks? The Abbot said something about this when we first met, and I’ve noticed that many of the Brothers always wear their cowls up indoors and outdoors.”

Phillip paused a while before answering.

“That’s two questions really,” he said. “Yes there are degrees of course, under the Abbot. Degrees of responsibility in the running of the Abbey and degrees of religious initiation. But the wearing of hoods is only indirectly related to this. Some of our brethren prefer this ultimate in withdrawal, this final abasement of self, the concealment of the face, or most of it anyway. It’s a logical spiritual step, if that’s not a contradiction.”

“It must make things rather difficult. Surely you want to be able to recognize people at some time.”

“Why? We are interchangeable, equal before God. Even our names are borrowed. We have them chosen for us on arrival.”

“Do you shed your old identities completely?”

Phillip laughed.

“That would be very difficult. We are still under the Law here. We must report ourselves according to the dictates of the Law.”

“And your heart clocks?”

Phillip looked at him quizzically.

“When our time is up, we must be accounted for like anyone else.”

“But I thought the Meek would inherit the earth?”

“A metaphor, Mr. Matlock. A metaphor.”

Matlock grunted, trying not to sound too disbelieving. His mind was once again sharpening for action and he didn’t want to show the full depth of his dissatisfaction. There was much here in need of investigation and he was not altogether certain whether Phillip was merely his guide or also his guard.

That evening Matlock made a great play of borrowing a history of the Abbey, saying he was going to get some real insight into the traditions and aims of the place. He almost overdid it for Phillip became very keen to stay with him in the Strangers’ House and guide him through the labyrinthine chapters of the massive tome, but Matlock finally persuaded him to leave the discussion till the morning and join the others in the usual pre-midnight service.

“They’ll drum you out if you don’t start paying more attention to your religion and less to me,” he said lightly.

“Same thing,” said Phillip, “you’re the lost sheep.”

Blacksheep, thought Matlock as he watched Phillip move across the grass to the church. Then he turned swiftly and went back to his room. He had chosen this particular time for two reasons. The first was that in a few minutes nearly all the monks, including the Abbot, would be participating in the service. The second was that the watchers in the tower would be more easy to fool if they happened to be scanning the area between the Strangers’ House and the main buildings. At least he hoped so, as he pulled from his bed the tattered remnants of the blanket he had spent the previous night hacking to pieces. Now he draped it over his shoulders and carefully set another piece on his head.

He only had a small shaving mirror and from what he could see of himself in that, he didn’t look much like a monk. But he hoped that on the television screen, if he was unfortunate enough to appear there, his shadowy image would pass muster.

He moved to the door of the Strangers’ House and peered out into the darkness. He saw a couple of figures move swiftly across an open space, then they disappeared into the shadows. Taking a deep breath as though he was about to dive into water, he stepped out into the night.

When he reached the protecting wall of the main building, he felt a sense of relief but recognized it instantly as premature. He had no way of telling if he had been observed or, if observed, whether he had been detected in his disguise. But there was nothing else to do now but continue with his plan.

Plan was perhaps rather too organized a word for what he had in mind, he thought as he slipped through the low arched door into the Cellarium, the Abbey’s main store-house. His destination was the Abbot’s private rooms and his purpose — he shrugged, and the blanket nearly slipped off his shoulders. To look around. To test a few suspicions. To do something instead of waiting for something to be done to him.

It was eerie down here in the Cellarium. Almost as long as the church, but much lower roofed, the building was totally unlit, and he stood for a while till his eyes grew used to the darkness.

Gradually the long row of central pillars began to form themselves out of the darkness like an exercise in perspective; then the arches of the vaults which sprang out of them. And finally, prosaically, the shadowy shapes and forms of the crates, boxes and cans of provisions which packed the vaults.

Distantly he heard the now familiar line of chanting which told him the service was under way. As quietly as possible, he made his way across the Cellarium and through the door that led into the cloister court. Compared with the darkness he left behind him, thin starlight glinting on the faintly damp grass was very bright indeed. He kept to the right, as far as possible moving always in shadow. He had no anticipation of meeting anyone, but the instinct of self-preservation seemed to have strengthened in him during the past few days.

I have the cloak, he thought hugging his blanket closer. Now I only need the dagger.

Surprisingly, he suddenly felt in need of a weapon. The gun he had had with him when he first came to the Abbey had disappeared during his first sleep. He hadn’t thought it worth mentioning to Phillip. Either he would know, in which case he would be an accessory to the theft. Or he wouldn’t know. In which case he wouldn’t know.

In any case it had been Francis’ gun.

Francis. He hadn’t had even a glimpse of him since the first day. Matlock surprised a sentimental fondness for the man in himself. They had been through trouble together. Such things had an illogical binding power.

But Francis was very firmly the Abbot’s man. Never forget that.

The thought of the Abbot suddenly snapped his mind back to the present. He had been moving forward with a stealth which was purely physical. His mind had been only half concerned with his progress. And his return to full alertness almost came too late.

He was just at the corner of the court nearest the arch which led through into the Chapter House. Inside he heard the shuffle of sandalled feet.

Silently he moved sideways till he came up against the wall.

Out of the Chapter House came a cowled figure who walked slowly, as though in deep thought, over the square of bright grass.

Читать дальше