Айзек Азимов - Before The Golden Age

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Айзек Азимов - Before The Golden Age» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

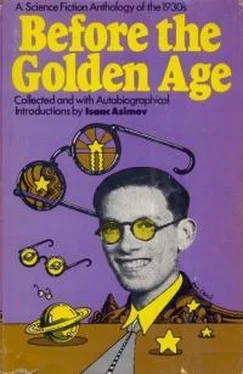

- Название:Before The Golden Age

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Before The Golden Age: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Before The Golden Age»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Before The Golden Age — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Before The Golden Age», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Doubleday published his The Crystal Man, dealing with nineteenth-century American science fiction. Sam even wrote an account of the tremendous and earth-shaking feuds among the handful of science fiction fans in the American Northeast, which he very dashingly entitled The Immortal Storm.

It was to Sam Moskowitz that I therefore turned. Swearing him to secrecy, I asked him if he had ever himself done an anthology of this sort and if he was in the process of doing so. He answered, no, he hadn’t and he wasn’t. He would like to if he could find a publisher.

“Well, I can,” I said, “and I would make it an autobiographical anthology. Would you object if I moved in on your territory?”

He sighed a little and said that he didn’t.

Then I reached the crucial point. “Would you get me the stories, Sam?” I asked.

And goodhearted Sam said, “Oh, sure!” and in three weeks he had them, every one, with word counts and copyright information and comments on each. (I was only too glad to pay him for the time and trouble he took.)

So now here I am, all set to do the anthology, and, if you don’t mind, I intend to make it more than a mere anthology. I am not going to include the stories bareboned.

With your permission (or without, if necessary), I intend to do as I did in The Early Asimov and place the stories within the context of my life. As I told Larry, Michele, and Sam, I intend the book to be autobiographical.

I am doing this partly because one pronounced facet of my personality is a kind of cheerful self-appreciation (“a monster of vanity and arrogance” is what my good friends call me) but also, believe it or not, as a matter of self-protection and as almost a kind of public service.

My numerous readers (bless them, one and all) never tire of writing letters in which they ask eagerly after all the most intimate statistics of my early life, and it has long since passed the point where I can possibly satisfy them, one by one, and still find time to do anything else. The Early Asimov has already performed miracles in that respect, since I can send back post cards saying, “Please read The Early Asimov for the information you request.”

And now I will be able to add, “Also read Before the Golden Age.”

Part One

1920 TO 1930

I HAVE always wanted to start a book in the fashion of a nineteenth-century novelist. You know: “I was born in the little town of P---------- in the year 19--.” Here’s my chance:

I was born in the little town of Petrovichi (accent on the second syllable, I believe), in the U.S.S.R. I say the U.S.S.R. and not Russia, because I was born two years after the Russian Revolution.

More than once, I have been asked where Petrovichi is relative to some place that might be considered reasonably familiar. It is thirty-five miles due west of Roslavl and fifty-five miles due south of Smolensk (where a great battle was fought during Napoleon’s invasion of 1812, and another during Hitler’s invasion of 1941), but that doesn’t seem to help any. I had better say, then, that Petrovichi is 240 miles southwest of Moscow and fifteen miles east of the White Russian S.S.R., so I was born on the soil of Holy Russia itself, for what that’s worth.

The date of my birth is January 2, 1920. For those of you who are interested in casting horoscopes, forget it! I am not only unaware of the exact hour and minute of my birth but even, actually, of the exact day. January 2 is the official day and that’s what I celebrate, but at the time of my birth the Soviet Union was on the Julian calendar, which was thirteen days behind our Gregorian, and my parents in those days didn’t even pay much attention to the Julian. They dated things according to the holy days of the Jewish calendar.

Under the Tsars, Russia had never indulged in careful statistical accounting of its less important subjects, and during World War I and the hectic years immediately following, things were more slovenly than ever. So when a birth certificate finally had to be drawn up for me, my parents had to rely on memory, and that worked out to January 2.

And that’s good enough. Anyway, it’s official.

I remained in the Soviet Union for less than three years and remember nothing of those days except for a few vague impressions, some of which my mother claims she can date back to the time I was two years old.

About the only event of personal note worth mentioning from those years is the fact that sometime in 1921 I fell ill of double pneumonia at a time when antibiotics were non-existent and such medical care as did exist was extremely primitive. My mother tells me (though I never know how much to allow for her innate sense of the dramatic) that seventeen children came down with it in our village at that time and that sixteen died. Apparently, I was the sole survivor.

In 1922, after my sister, Marcia, was born, my father decided to emigrate to the United States. My mother had a half brother living in New York who was willing to guarantee that we would not become a charge on the country; that, plus permission from the Soviet Government, was all we needed.

I am sometimes asked to give the details of how we left the Soviet Union, and I get the distinct feeling that the questioners will be satisfied with nothing less than having my mother jumping from ice floe to ice floe across the Dnieper River with myself in her arms and the entire Red Army hot on our heels.

Sorry! Nothing like that at all! My father applied for an exit visa, or whatever it’s called, got it, and off we went by commercial transportation. While we were getting the visa, the family had to go to Moscow, so in the year 1922 I was actually there. My mother says the temperature was forty below and she had to keep me inside her coat lest I freeze solid, but she may be exaggerating.

Needless to say, I am not sorry we left. I dare say that if my family had remained in the Soviet Union, I would have received an education similar to the one I actually did get, that I might well have become a chemist and might even have become a science fiction writer. On the other hand, there is a very good chance that I would then have been killed in the course of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 to 1945, and while I hope I would have done my bit first, I am glad I didn’t have to. I am prejudiced in favor of life.

The four of us—my father Judah, my mother Anna, my sister Marcia, and myself—traveled by way of Danzig, Liverpool, and the good ship Baltic, and arrived at Ellis Island in February 1923. It was the last year in which immigration was relatively open and in which Ellis Island was working full steam. In 1924, the quota system was established and the United States began to welcome only sharply limited amounts of the tired, the poor, and the wretched refuse of Europe’s teeming shores.

One more year, then, and we wouldn’t have made it. Even if we could have come in at some later time, it wouldn’t have been the same. Arriving at the age of three, I was, of course, already speaking (Yiddish), but I was still young enough to learn English as a native language and not as an acquired one (which is never the same).

My parents, both of whom spoke Russian fluently, made no effort to teach me Russian, but insisted on my learning English as rapidly and as well as possible. They even set about learning English themselves, with reasonable, but limited, success.

In a way, I am sorry. It would have been good to know the language of Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoevski. On the other hand, I would not have been willing to let anything get in the way of the complete mastery of English. Allow me my prejudice: surely there is no language more majestic than that of Shakespeare, Milton, and the King James Bible, and if I am to have one language that I know as only a native can know it, I consider myself unbelievably fortunate that it is English.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Before The Golden Age»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Before The Golden Age» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Before The Golden Age» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.